Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Mpilo Tutu (1931 - 2021)

St John’s College notes with great sadness, and with a profound sense of loss, the death of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu. The College is proud of its association with the late Archbishop, who stands in the first rank of the pantheon of South Africa’s greatest sons and daughters.

Over several decades, Archbishop Tutu was, with justification, regarded as the moral conscience of our nation – a man who courageously resisted apartheid injustices and who consistently spoke truth unto power. We take this opportunity to pay tribute to him and to express our gratitude for the invaluable contributions he made to St John’s College and to South African society.

The association between the late Archbishop Tutu and St John’s College finds its origins in their mutual links with the Community of the Resurrection. The Community of the Resurrection, a monastic order of Church of England priests and lay brothers, initially sent some of its members to Johannesburg in 1903 to undertake mission work among African workers employed on the gold mines. The Community soon expanded its presence on the Witwatersrand and became involved in a range of other social projects. In particular, the Community took charge of the Sophiatown Native Mission and St Cyprian’s School (established by our founder, the Rev John Darragh), which was attached to that mission. In 1904, the Community established St Peter’s Theological College in Rosettenville as a seminary for training aspirant black Anglican clergymen. In 1906, the Community took charge of St John’s College. In 1908, the Community started St Agnes’ School for black African girls in Rosettenville. This was followed by the establishment of St Peter’s School for boys, also in Rosettenville, in 1922. It was the only secondary boarding school for black Africans in the Transvaal.

Born at Klerksdorp on 7 October 1931, Desmond Tutu and his family lived in Sophiatown in the 1940s. There he came into contact with some of the brethren of the Community of the Resurrection, who ran the Anglican parish in Sophiatown. They included Fr Raymond Raynes CR (who had previously taught at St John’s College) and Fr (later Archbishop) Trevor Huddleston CR.

In 1947, when he was fifteen years old, Desmond Tutu was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The CR fathers arranged for him to receive treatment at Rietfontein hospital, on the eastern outskirts of Johannesburg, where he remained for 21 months. During this confinement, he received regular visits from Fr Huddleston, to whom he made his confessions, and from Fr Dominic Whitnall CR, who brought him books to read.

In the 1950s, the late Archbishop Tutu studied at St Peter’s Theological College in Rosettenville, which was run by the Community of the Resurrection. He was ordained as an Anglican minister at St Mary’s Cathedral, Johannesburg, in December 1960.

In 1962, Fr Aelred Stubbs CR arranged for Archbishop Tutu to pursue further studies in theology at King’s College London. (Fr Stubbs was the principal of St Peter’s College, and represented the Community of the Resurrection on the Council of St John’s College in the 1970s.) Archbishop Tutu obtained an MA degree from King’s College London in 1966. He then became the Anglican chaplain at the University of Fort Hare, a position he held from 1967 to 1969. In 1970, he became a lecturer and chaplain at the University of Botswana, Lesotho & Swaziland at Roma in Lesotho.

In August 1975, Archbishop Tutu was appointed Dean of St Mary’s Cathedral, Johannesburg. St John’s College had originally, in 1898, been established as a parish school of St Mary’s Church. As the Anglican diocesan college for boys in Johannesburg, St John’s College retained close links to St Mary’s Cathedral, where the school still holds its annual Carol Service.

In May 1976, Archbishop Tutu (then Dean of Johannesburg) came to St John’s College for a five-day silent retreat. During this retreat he wrote a poignant and prophetic letter to Prime Minister John Vorster, in which he expressed his concerns about apartheid repression and its implications for the future of our country:

‘I write to you, sir, because, like you, I am deeply committed to real reconciliation with justice for all and to peaceful change to a more just and open South African society in which the wonderful riches and wealth of our country will be shared more equitably. I write to you, sir, to say … that the security of our country ultimately depends not on military strength and a security police being given more and more draconian power to do virtually as they please without being accountable to the courts of our land ... . How long can a people, do you think, bear such blatant injustice and suffering? Much of the white community by and large, with all its prosperity, its privilege, its beautiful homes, its servants, its leisure, is hag-ridden with a fear and a sense of insecurity ... . And this will continue to be the case until South Africans of all races are free. Freedom, sir, is indivisible. The whites in this land will not be free until all sections of our community are genuinely free ... . We need one another and blacks have tried to assure whites that they don't want to drive them into the sea. How long can they go on giving these assurances and have them thrown back in their faces with contempt? ...

I am writing to you, sir, because I have a growing nightmarish fear that unless something drastic is done very soon then bloodshed and violence are going to happen in South Africa almost inevitably. A people can take only so much and no more ... A people made desperate by despair and injustice and oppression will use desperate means. I am frightened, dreadfully frightened, that we may soon reach a point of no return, when events will generate a momentum of their own, when nothing will stop their reaching a bloody denouement which is “too ghastly to contemplate” to quote your words, sir ... . But we blacks are exceedingly patient and peace-loving. We are aware that politics is the art of the possible. We cannot expect you to move so far in advance of your voters that you alienate their support ... . We are ready to accept some meaningful signs which would demonstrate that you and your government and all whites really mean business when you say you want peaceful change ... . I believe firmly that your leadership is quite unassailable and that you have been given virtually a blank cheque by the white electorate and you have little to fear from a so-called right-wing backlash ... . For if the things which I suggest are not done soon, a rapidly deteriorating situation arrested, then there will be no rightwing to fear - there will be nothing ... .’

Prime Minister Vorster ignored Archbishop Tutu’s letter. A few weeks later, on 16 June 1976, the Soweto uprising broke out. Shortly afterwards, in August 1976, Archbishop Tutu was installed as Bishop of Lesotho. In September 1977, he spoke at the funeral of the Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko, who had died as a result of injuries sustained from assaults while in police custody. In 1978, Archbishop Tutu was appointed general secretary of the South African Council of Churches. In this capacity, he became an increasingly prominent critic of the apartheid regime. He advocated non-violent means of protest and encouraged the enforcement of economic sanctions against the regime. In August 1983, he was elected one of the patrons of the United Democratic Front, which was at the forefront of the mass democratic movement’s anti-apartheid struggle. In December 1984, he received the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of the significant work he was doing to promote a peaceful transition to a more just and open society in South Africa.

In February 1985, Archbishop Tutu was enthroned as Bishop of Johannesburg. The Headmaster of St John’s College, Mr Walter Macfarlane, attended the enthronement ceremony at St Mary’s Cathedral. In his capacity as Bishop of Johannesburg, Archbishop Tutu became the Visitor of St John’s College – the highest position in the College’s institutional hierarchy. Many in the (predominantly white) St John’s community were apprehensive about having a Visitor with such a high political profile. Many white South Africans regarded him with suspicion and even animosity. Mr Macfarlane invited Bishop Tutu to come and spend a day at St John’s. By the end of the day, his warmth, humanity and sense of humour had endeared him to all. Soon he was a much-loved and greatly respected Visitor.

In February 1986, Archbishop Tutu was awarded the Martin Luther King Jr Peace Prize. He was enthroned as Archbishop of Cape Town at St George’s Cathedral in September 1986. He was the first black man to be elevated to this position, which he held until June 1996. In this capacity, he was head of the Church of the Province of South Africa. Upon his retirement from this position, Archbishop Tutu was awarded the Order for Meritorious Service (South Africa’s highest honour) by President Nelson Mandela.

In 1996 he became the first recipient of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Award for Outstanding Service to the Anglican Communion. He was chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission from April 1996 until October 1998.

In 2003, Archbishop Tutu and ex-President Mandela attended the opening of the Desmond & Leah Tutu Bridge linking St John’s College and Roedean School. Archbishop Tutu was also the guest of honour on Gaudy Day in 2005 and, on that occasion, was the celebrant at the community mass on Mitchell Field. In his homily, he inspired the College community, in his inimitable manner, to redouble efforts to assist the needy. ‘God,’ he said, ‘is not going to make Big Macs and Levi’s rain down from heaven to feed the hungry and clothe the poor. He relies on us to step up and be his agents.’ More recently, Archbishop Tutu’s great-nephew, Ekow Daniels, attended St John’s College.

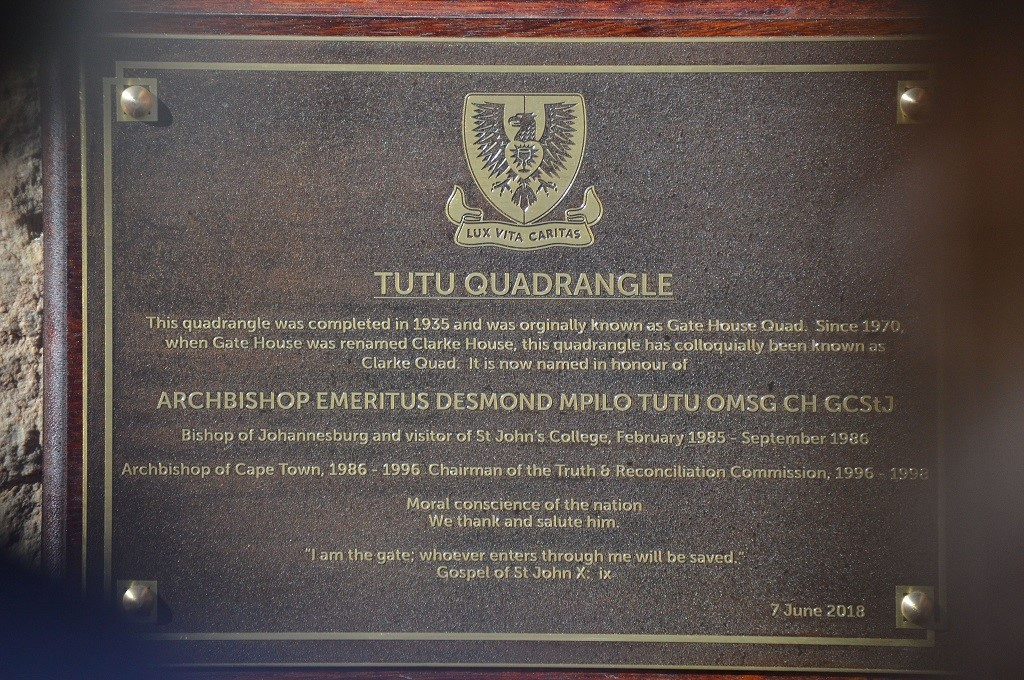

In 2018, St John’s College requested Archbishop Emeritus Tutu’s permission to rename Gate House Quadrangle (colloquially known as Clarke Quad) after him in recognition of the link between him, the Community of the Resurrection and St John’s College; the fact that he wrote his important letter to Prime Minister Vorster while he was at St John’s College in May 1976; the fact that he was ex officio Visitor to St John’s College in 1985 – 1986; the fact that he was one of the most prominent opponents of the apartheid regime in the 1970s and 1980s, bravely taking a stand against an evil and brutal system; and his work as chairman of the TRC.

Archbishop Tutu kindly acceded to the College’s request, and described the naming of the quadrangle after him as “a great honour by an institution I have admired for a long time.” A bronze bust of Archbishop Tutu, capturing his fatherly smile, was installed in Tutu Quadrangle in 2019. He subsequently gave us a pair of his shoes, which were bronzed and installed in the quadrangle in such a way that viewers of the bust can put their feet in his shoes while reflecting on his great life and his contribution to humanity.

Our nation is greatly diminished by the death of Archbishop Emeritus Tutu. We shall remember him fondly and with pride, and hope that current and future generations of Johannians will find inspiration in the manner in which he upheld the principles and values held dear by our College community. He deserves to be held up to us all as the epitome of virtue, integrity, compassion and heroism. He personified Lux Vita Caritas.

Principal sources:

The Johannian; T Huddleston Naught for Your Comfort (1956); A Wilkinson The Community of the Resurrection (1992); D Tutu No Future Without Forgiveness (1999); OM Suberg The Anglican Tradition in South Africa (1999); J Allen Desmond Tutu: Rabble-Rouser for Peace (2006); SD Gish Desmond Tutu: A Biography (2004); Encyclopaedia Britannica