by Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

1899

‘A local Winchester’

At the time of the establishment of St John’s College in 1898, the Johannesburg newspaper Standard & Diggers’ News had expressed scepticism, if not opposition, in respect of the founding of an Anglican denominational school for boys. The editor soon changed his mind. In February 1899, the newspaper congratulated ‘the youngest scholastic institution in our midst on the success it has already achieved.’ The editorial article said, under the heading ‘A Local Winchester’, that St John’s College’s modest but convenient premises in Plein Street were ‘not likely to attract attention by reason of “hallowed halls in ivy clad”, but it may be the foundation of just such a College as the old country rightly prides itself upon. If our millionaires would but see to the halls nature may be depended on for the ivy in due time.’

The editor proceeded as follows:

‘The new school owes its existence to the efforts of a few Churchmen, ladies of the congregation of St Mary’s assisting in raising the fund of £800 on which it was started, the capitalistic element refusing point-blank to give any help. Less than six months ago, St John’s started with a dozen boys, and to-day provision has to be made for ninety ... The aim is to establish a high-class public school of a select kind, with the tone characteristic of similar schools in England. Special features are the teaching of Dutch as a compulsory subject, and physical training, in addition to the mind culture provided in the ordinary curriculum. ... The Principal, the Rev J. L. Hodgson, M.A., formerly Assistant Master and Chaplain at King’s College, Taunton, Somerset, has made an excellent start ... . St John’s College, and its needs, should touch a chord in the hearts of those who have obtained honourable positions largely because of efficient training in schoolboy days.’

When the editor of the Standard & Diggers’ News wrote that the aim of St John’s College was to establish ‘a high-class public school … with the tone characteristic of similar schools in England,’ he was using the term ‘public school’ in its traditional British sense. In the United Kingdom, some independent schools (schools of the nature generally called ‘private schools’ in South Africa) have traditionally been known as ‘public schools’. Under the Public Schools Act of 1868 only seven schools – all of them ancient boys’ boarding schools – were originally regarded as ‘public schools’: Charterhouse (founded in 1611), Eton (1440), Harrow (1571), Rugby (1567), Shrewsbury (1552), Westminster (1561) and Winchester (1382). As such, when the editor called St John’s College ‘a local Winchester’ he was paying it the supreme compliment of likening it to one of England’s oldest and most famous schools – never mind that, in reality, the St John’s College of 1899 bore precious little resemblance (beyond wishful aspiration) to schools such as Winchester.

As St John’s College was regarded as approximating to ‘a high-class public school … with the tone characteristic of similar schools in England’ (at least in theory) it might be apposite to interpose here an attempt to provide a description of that type of institution of that period. In an endeavour to understand the nature of English public schools of the Victorian age, one could do worse than turn to the work of Thomas Hughes, who had attended Rugby School in the 1830s, when the famous Dr Thomas Arnold was its headmaster. Hughes is remembered mainly as the author of Tom Brown’s School Days (1857), an iconic work of English schoolboy fiction. However, he was also a county court judge and a reformist Member of Parliament.

In 1879 (nineteen years before St John’s College was founded), Hughes wrote a series of articles in which he sought to enlighten American readers on the nature of English public schools. He explained that ownership of a public school’s property is vested in its governing body, which has no pecuniary interest in the school but controls its expenditure, and has power to appoint (and remove) the headmaster, and to determine admissions policies, fees, salaries, and the curriculum. How the curriculum is taught is left to the headmaster, who has control over the administration of admissions, studies and internal discipline of the school, and who appoints all staff.

Hughes highlighted other distinctive features of public schools. Generally they were ecclesiastical establishments with their own chapels. They implemented a monitorial system of self-government in terms of which authority was delegated to school and house prefects to oversee boys’ activities and conduct. They had systems of ‘fagging’ according to which junior boys were required to perform certain ‘trifling’ services for senior boys, who were expected to reciprocate by providing protection and advice to juniors. Perhaps most fundamentally, public schools sought to inculcate character and gentlemanly manners in boys.

These time-honoured English public schools were not set up by the state. Rather, they were founded by pious and philanthropic bequests as charitable grammar schools intended to educate indigent children in particular localities. They were not funded by the state but from benefactors’ endowments and fees paid by pupils (although they had ‘foundation’ pupils entitled to education which was wholly or partly gratuitous). As the reputation of some of these schools began to spread beyond their immediate environs, they began to attract pupils from further afield. Parents who could afford to pay residential fees, rather than local parents only, sent their children to these schools, which in that sense became ‘public’ institutions. Victorian parents tended to send sons rather than daughters to these schools, and so public schools became synonymous with boys’ boarding schools.

The process by which these local schools became ‘public’ schools is described by William Makepeace Thackeray (himself an alumnus of Charterhouse) in his novel Vanity Fair (1848):

‘His lordship extended his goodwill to little Rawdon: he pointed out to the boy’s parents the necessity of sending him to a public school; that he was of an age now when emulation, the first principles of the Latin language, pugilistic exercises, and the society of his fellow-boys would be of the greatest benefit to the boy. His father objected that he was not rich enough to send the child to a good public school; … but all these objections disappeared before the generous perseverance of the Marquis of Steyne. His lordship was one of the governors of that famous old collegiate institution called the Whitefriars. It had been a Cistercian Convent in old days … . Henry VIII, the Defender of the Faith, seized upon the monastery and its possessions, and hanged and tortured some of the monks who could not accommodate themselves to the pace of his reform. Finally, a great merchant bought the house and land adjoining, in which, and with the help of other wealthy endowments of land and money, he established a famous foundation hospital for old men and children. An extern school grew round the old almost monastic foundation, … and all Cistercians pray that it may long flourish.

Of this famous house, some of the greatest noblemen, prelates, and dignitaries in England are governors: and as the boys are very comfortably lodged, fed, and educated, and subsequently inducted to good scholarships at the University and livings in the Church, … there is considerable emulation to procure nominations for the foundations. It was originally intended for the sons of poor and deserving clerics and laics; but … [t]o get an education for nothing, and a future livelihood and profession assured, was so excellent a scheme, that some of the richest people did not disdain it … .

Rawdon Crawley, though the only book which he studied was the Racing Calendar, and though his chief recollections of polite learning were connected with the floggings which he received at Eton in his early youth, had that … reverence for classical learning which all English gentlemen feel, and was glad to think that his son was to have a provision for life, perhaps, and a certain opportunity of becoming a scholar. …

In the course of a week, young Blackball had constituted little Rawdon his fag, shoe-black, and breakfast toaster; initiated him into the mysteries of the Latin Grammar, and thrashed him three or four times; but not severely. The little chap’s good-natured honest face won his way for him. He only got that degree of beating which was, no doubt, good for him; and as for blacking shoes, toasting bread, and fagging in general, were these offices not deemed to be necessary parts of every young English gentleman's education? …

Rawdon marvelled over his [son’s] stories about school, and fights, and fagging. … He tried to look knowing over the Latin grammar when little Rawdon showed him what part of that work he was “in”. “Stick to it, my boy,” he said to him with much gravity, “there's nothing like a good classical education! Nothing!”’

E. M. Forster (an old boy of Tonbridge School, founded in 1553) described the same process in his novel The Longest Journey (1907):

‘Sawston School had been founded by a tradesman in the seventeenth century. It was then a tiny grammar-school in a tiny town, and the City Company who governed it had to drive half a day through the woods and heath on the occasion of their annual visit. In the twentieth century they still drove, but only from the railway station; and found themselves not in a tiny town, nor yet in a large one, but amongst innumerable residences … which had gathered round the school. For the intentions of the founder had been altered … instead of educating the “poore of my home”, he now educated the upper classes of England. The change had taken place not so very far back. Till the nineteenth century the grammar-school was still composed of day scholars from the neighbourhood. Then two things happened. Firstly, the school’s property rose in value, and it became rich. Secondly, … it suddenly emitted a quantity of bishops. The bishops, like the stars from a Roman candle, were all colours, and flew in all directions, some high, some low, some to distant colonies, one into the Church of Rome. But many a father traced their course in the papers; many a mother wondered whether her son, if properly ignited, might not burn as bright; many a family moved to the place where living and education were so cheap, where day-boys were not looked down upon, and where the orthodox and the up-to-date were said to be combined. The school doubled its numbers. It built new class-rooms, laboratories and a gymnasium. It dropped the prefix “Grammar”. … And it started boarding-houses. It had not the gracious antiquity of Eton or Winchester, nor, on the other hand, had it a conscious policy like Lancing, Wellington, and other purely modern foundations. … It aimed at producing the average Englishman, and, to a very great extent, it succeeded.’

As the concluding sentence of the Thackeray extract quoted above indicates, public schools’ curricula traditionally focused on the Classics, especially Latin and Greek grammar and literature. Gradually, though, it came to be appreciated that ‘education’ had to extend beyond academic instruction to ‘gentlemanly virtues’, leadership, ‘moral character’ and the ideal of mens sana in corpore sano. In this regard, the British Prime Minister, Lord John Russell. wrote the following in 1865:

‘The object of education is not only to store the mind, but to form the character. It is of little use that a boy has a smattering of mineralogy, and is very fluent at botanical names; it will be of no avail to him to talk of argil and polyandria, if he cries when he loses at marbles, and is lifeless or timid when he is obliged to play cricket. Now a public school does form the character. … His character, in short, is prepared for the buffetings of grown men … this is of much more importance than the acquisition of mere knowledge.’

Francis Duckworth, who was educated at Rossall (founded in 1844) and who taught at Eton, and who became Chief Inspector of the Board of Education in England in the 1920s, wrote an amusing story in which an Englishman tried to explain the purpose and value of English public schools to a German visitor. The narrator conceded that Victorian and Edwardian public schools had many imperfections:

‘A boy when he leaves a Public School at the age of eighteen will very likely imagine that Michelangelo was a musician, or that Handel wrote comic verse. He will be unable to tell you the difference between rates and taxes. He will not know the name of the present French Premier or the names of the battles in the Russo-Japanese War. He will not even know the difference between Cabinet and Parliament. He will be master of barely enough arithmetic to keep his own accounts, but as he is probably unwilling to keep any – that hardly matters. Science he may never have touched – he will probably imagine that radium is a vegetable. Latin and Greek have been almost his sole study for something like ten years; yet out of a hundred such boys barely fifteen will be able to turn the easiest piece of English into Latin without the most ridiculous grammatical blunders. They will know a great deal of Roman history of the period which is of least general importance – they “end with the death of Augustus.” As for their Greek …’

At this point the German tourist interrupted the narrator to ask whether he intended to send his son to a gymnasium in Germany. But the Englishman, his eyes twinkling with pride and pleasure, said that he was resolved to send his son to the same public school as he had attended, and which had left him ignorant of the locality of the Bismarck Straits. He explained that his decision to send his son to his old alma mater was not attributable to the fact that, since his days, public schools had awoken to their own weaknesses and had acquired laboratories and lecture theatres. Indeed, he would send his son to the same public school even if it had made no progress since his days:

‘He can get in a Public School what he could not get anywhere else in any country. He will learn self-reliance, and will acquire certain other moral qualities – a sense of duty and fellowship, a knowledge of how to command and obey. I am not an athleticist. He will of course play games, and he must be keen on representing his school. But even if he should really be a rotter at games, he will learn the Public School Tradition.’

He continued to describe the typical master in a public school:

‘He is a man who had himself received a good liberal education at Public School and University … a broad-minded man of wide interests. … He is a person remembered by his pupils afterwards with increasing respect and affection. He is fully alive to his responsibilities – he spares himself in no way, and besides his routine work, will nearly always take on some extra unsalaried job for the school’s good: he will manage the cadet corps or the tuck-shop … ready to help with games as well as work. Let me quote an instance – my old House Master. There was a scholar and a gentleman! He had taken First Classes at Oxford in Classical Schools, and he had rowed in the ‘Varsity VIII. … I never met a warmer-hearted man or one entered more deeply into all the interests of a boy. There was no trouble which I did not confide to him, and in all he was able to help me. He would tolerate no meanness or slackness in any one; he was judicious in his praise, and when he could help others he never considered himself. … He had never at any period a salary of more than £300 a-year … and yet he was responsible, body and soul, for at least forty-five boys. Such services as his are not bought for money.’

Not infrequently, it must be said, public schools imparted attributes such as ‘gentlemanly virtues’ and ‘moral character’ in a maladroit manner. Aspects of the methodology adopted by public schools of yore certainly seem unduly spartan to modern sensibilities. Even a century ago that system reminded Herbert Gray (a former headmaster of Bradfield College) of ‘quasi-Norman feudalism’.

That notwithstanding, so esteemed an institution did the public school become in the upper echelons of English society that a genre of public school fiction developed. The most famous (but not the first) of these prose works was Tom Brown’s Schooldays. References to such schools abound in works of literature produced in England and elsewhere. These range from the sublime to the ridiculous. The best-known (but not the best) boys’ school stories are Frederic Farrar’s Eric, or, Little by Little (1858), Rudyard Kipling’s Stalky & Co (1899), Franks Richards’ Billy Bunter (1908) and Anthony Buckeridge’s Jennings (1950). More interesting are P. G. Wodehouse’s Enter Psmith (1909), Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall (1928), James Hilton’s Goodbye Mr Chips (1934) and, of course, J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter (1997). American variations on the theme include J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951), Donna Tartt’s The Secret History (1992) and Tobias Wolff’s Old School (2003). South African examples include Topsy Smith’s Leon at Clan College (1963) and John van de Ruit’s Spud (2005).

Although ‘public schools’ are often treated as one monochromatic category, many of them developed their own idiosyncratic traditions, games and, in some cases, even vernacular – so much so that the historian Sir Arthur Bryant wrote that the ritual of a great public school was ‘as intricate and finely woven as a Beethoven sonata’. Even houses within schools – microcosms of the greater institutions – acquired unique customs and identities. Successive generations of public-school boys retained an abiding sense of allegiance to their old schools and houses.

But let us not digress too much from the story of St John’s College.

Nowadays we are accustomed to the College’s academic year being divided into Easter, Trinity and Michaelmas trimesters. In those days, however, St John’s had four terms: Lent, Easter, Trinity and Advent. The quarterly system was followed for the sake of uniformity with other local schools, and because it was thought that a term of thirteen weeks’ duration would be ‘too great a strain for both staff and boys at this altitude.’ The three-term system was only adopted in 1973, and so is not of such ancient provenance as might be supposed.

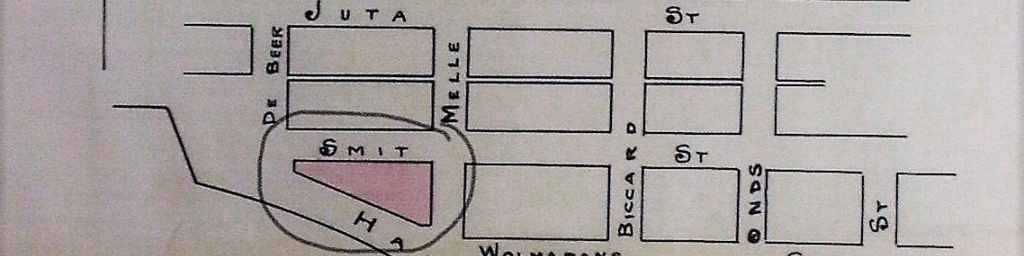

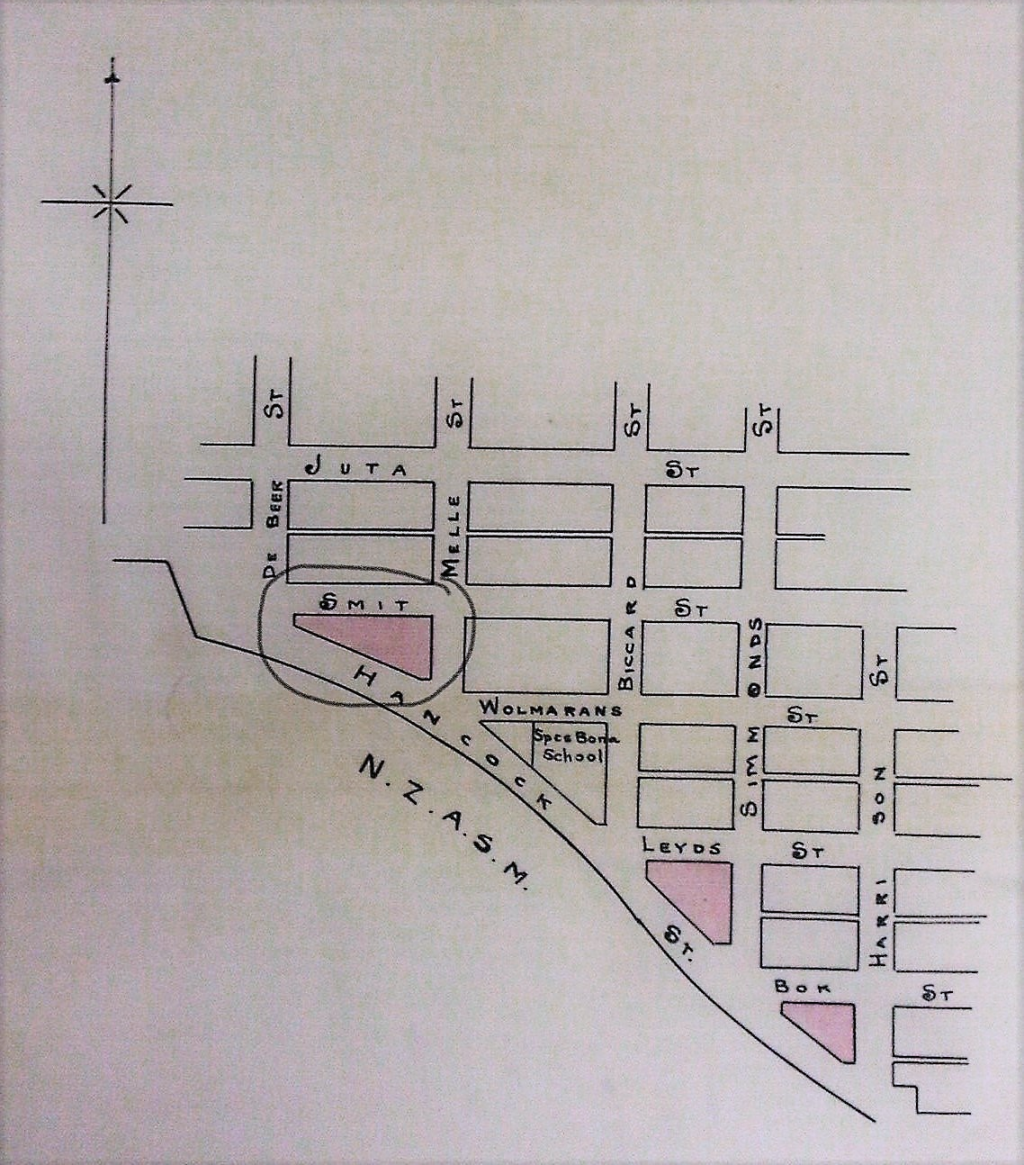

By the end of Lent Term of 1899, in excess of a hundred boys were enrolled at St John’s College. At the end of Easter Term, the Standard & Diggers’ News enthused: ‘Success was almost embarrassing as [the College’s] temporary premises were outgrown before a more suitable building could be erected.’ However, by this time war clouds were gathering ominously on the horizons of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek. A peace conference held in Bloemfontein in June 1899 had failed to produce a resolution to the standoff between President Paul Kruger’s little republic and Her Majesty’s government. These unpropitious political circumstances notwithstanding, the Council of St John’s College was boldly exploring the possibility of obtaining a site for a new school building. The Council identified a triangular site in Braamfontein, bounded by Hancock, Smit and Melle streets, opposite the Nederlandsch Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg Maatschappij railway line, as its preferred location for the construction of a new home for the school.

However, even before application had been made to the municipal authorities for allocation of the site to St John’s, the Council’s plan encountered resistance. On 13 June 1899, Mr J. H. de Wit, headmaster of Spes Bona School (situated on a contiguous site at the corner of Wolmarans and Biccard streets) sent an objection to the Superintendent of Education. He wrote that construction of a building for St John’s on the proposed site would make the continued existence of his school in an unattractive little building (‘een onaanzienlijk gebouwtje’) impossible. On 3 August, De Wit sent a further letter to the Superintendent, in which he claimed (not veraciously) that construction of the new St John’s building had already commenced and that, once the building was ready, it would be fatal to his own school (‘de hunne den doodsteek zal geven’).

Notwithstanding this opposition (and the looming threat of war), the College Council resolved, in view of the school’s growing roll, to go ahead with plans for acquisition of the site in Braamfontein. The matter was taken up with the Johannesburg City Council with a view to obtaining its support, which was a prerequisite for obtaining approval from the Z. A. R. government. On 11 September 1899, the matter was placed before the City Council’s Public Works Committee, which supported the application for allocation of the site to St John’s College. The matter then served before the City Council on 15 September 1899. Councillor J. Holder moved, and Councillor P. J. van Os seconded the motion, that it be recommended to the government that the College’s application be approved. The motion was carried by the narrow margin of nine votes to seven.

On 19 September 1899, the City Council’s secretary forwarded the relevant extract from the minutes of the Council meeting, together with a certified translation (from English to Dutch) of St John’s College’s application to the Mayor of Johannesburg, with a request that these documents be sent to the government. The Mayor duly submitted the translated application and the minutes to the State Secretary on 28 September 1899.

On the same day, 28 September 1899, the chairman of the Spes Bona school commission, Mr C. R. Ochse, sent a letter to the Superintendent of Education. In this letter, he said that it was undesirable that land adjacent to that school be granted to St John’s College, and requested the Superintendent to exercise his influence with the government in opposition to the application by St John’s.

By a quirk of fate – or perhaps it was Providence – the outbreak of war, a fortnight later, precluded the acquisition of the Braamfontein site by St John’s College.

In August 1899, President Kruger had, in an effort to avert war, offered to extend the franchise to ‘uitlanders’ (foreigners) who had resided in the Z. A. R. for five years or longer. He had also offered to reserve a quarter of the seats in the Volksraad for uitlanders. However, Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, influenced by the British proconsul in South Africa, Sir Alfred Milner, declined to accept this offer. Kruger then reverted to an earlier offer of a seven-year residency requirement. Soon ten thousand British troops were dispatched to Natal.

On 9 October 1899, the Z. A. R. delivered an ultimatum to Her Majesty’s government: unless the troops advancing on the Z. A. R.’s frontiers were withdrawn within 48 hours, and unless Britain agreed to neutral arbitration of the impasse, her action would be regarded as a declaration of war. The ultimatum went unheeded. In reality, though, war had been approaching inexorably for months, and a precautionary exodus of British subjects from the Transvaal had been underway for some time. Thirty thousand civilians fled by rail from the Witwatersrand to the Cape and Natal; in their panicking desire to escape, many stood in open cattle trucks. Many businesses and mines on the Rand shut down. An eerie calm descended on Johannesburg.

The British government believed the Anglo-Boer South African War would last no more than a few months. British newspapers dubbed the campaign in South Africa ‘the Teatime War’ – they thought it would be all over by Christmas. Milner confidently predicted that the Boers would put up only ‘an apology’ of a fight. The British War Office Intelligence Department also did not see the Boers as a serious military rival. This optimistic orthodoxy accounted for the fact that, whereas the Boers had been spending £340,000 on gathering intelligence in the two years preceding the War, the request by the British Director of Military Intelligence for £10,000 per annum for counter-activity had been rejected; after some quibbling, he was grudgingly granted £100. Only in July 1898 had a group of officers been sent to South Africa for local recruitment and intelligence, but they were given ‘sums inadequate for the purposes of respectable commercial travellers.’

Those in the British corridors of power who expected the Boers to capitulate quickly were in for a chastening surprise. During ‘Black Week’ in December 1899, the Boers inflicted humiliating defeats on the Imperial Army at Kissieberg, Modder River and Colenso. This was followed by the ignominious disaster at Spioen Kop late in January 1900, where the British sustained 1,200 casualties.

However, the circumspect Boer generals failed to capitalise on their early strategic advantage: they committed large numbers of men to futile sieges at Mafeking, Ladysmith and Kimberley. Instead, they should have gone on the offensive while the bulk of the British forces were still en route to South Africa. The Boer commanders, lacking in military experience and tactical acuity, squandered this opportunity. Once imperial reinforcements had arrived, the numerical superiority of the British forces meant that it was probably only a matter of time before they overcame their Boer adversaries. By the beginning of 1900, the British commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar, had a field force of 180,000 men at his disposal. By the end of the War, the British had mobilised 450,000 soldiers. By contrast, the republican commandos never boasted more than 80,000 ‘burghers’ (citizens) supported by about 2,000 foreign volunteers and 12,000 black ‘agterryers’ (auxiliaries).

The battle at Paardeberg in February 1900 (where 4,069 Boer soldiers were captured) was a turning point. Sanguine British expectations about a swift end to the War seemed vindicated when advancing British columns captured Bloemfontein, without any resistance, on 13 March 1900. Lord Roberts notified Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, of his conviction that ‘it will not be very long before the war will have been brought to a satisfactory conclusion.’

Despite the evacuation of many civilians, life in Johannesburg – and at St John’s College – continued largely unaffected by the War for several months. However, once the Orange Free State (soon to become the Orange River Colony) had fallen to the British forces in March 1900, the situation in Johannesburg began to change. With the British columns advancing northward towards the Vaal River, more civilians began to depart from the Rand. Eventually, this was to have an unavoidable impact on St John’s College.

Principal sources:

Brooke-Smith Gilded Youth: Privilege, Rebellion & the British Public School (2019); Duckworth From a Pedagogue’s Sketchbook (1912); Farmer Public School Word-Book (1900); Giliomee & Mbenga New History of South Africa (2007); Gray The Public Schools and the Empire (1913); Harwood England’s Schools: History, Architecture and Adaptation (2012); Heywood ‘Boys at Public Schools’ in Pitcairn (ed) Unwritten Laws and Ideals of Active Careers (1899); Hughes ‘The Public Schools of England’ (1879) North American Review vol 128 352, vol 129 37; Kruger Goodbye Dolly Gray (1959); Levi ‘Colleges and Schools’ (1865) 14 Annals of British Legislation 297; Maclean The Law Concerning Secondary and Preparatory Schools (1909; Malim Almae Matres: Recollections of Some Schools at Home and Abroad (1948); Mangan Athleticism in the Victorian and Edwardian Public School (1981); Marples Public School Slang (1940); McConnell English Public Schools (1985); Meredith Diamonds, Gold & War (2007); Nasson The War for South Africa (2010); Neame City Built on Gold (1960); Pakenham The Boer War (1979); Pretorius ‘Private Schools in South African Legal History’ (2019); Rosenthal Gold! Gold! Gold! (1970); Russell Essay on the History of the English Government and Constitution from the Reign of Henry VII to the Present Time (1865); Shrosbree Public Schools and Private Education: The Clarendon Commission 1861-64 and the Public Schools Acts (1988); Stephen The English Public School (2018); Turner The Old Boys: The Decline and Rise of the Public School (2015); Various Authors Great Public Schools (1893); Warner English Public Schools (1946) Standard & Diggers’ News; National Archives