By Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

The year 1906 marked a momentous milestone in the history of St John’s College – a veritable watershed. It was the year in which the school was salvaged from its state of submersion and was gradually set on a steady course towards calmer seas. It was a process that provided firm foundations for the future development of the College on a sustainable basis, during which the school’s guiding principles and values began to assume manifestation. It was all largely attributable to the arrival at St John’s of a small contingent of friars from the Community of the Resurrection.

The Community of the Resurrection, a monastic order of Church of England priests and lay brothers, was founded in Oxford in 1892. It was part of the ‘Tractarian’ Oxford Movement, which advocated ‘High Church’ Anglo-Catholicism. The Anglo-Catholic movement aspired to enhance the Catholic character of the Anglican Church through its liturgical and sacramental doctrines and rituals. The first Superior of the Community of the Resurrection was Charles Gore (1853-1932, an Old Harrovian, a fellow of Trinity College, Oxford, and later Bishop of Worcester, Birmingham and Oxford). Although most of the men of the Community of the Resurrection came from patrician families and were urbane products of elite public schools and Oxbridge colleges, many of them were Christian Socialists. Prompted by a desire to work among the impoverished working classes, the Community decided to relocate from privileged Oxford (with its ‘dreaming spires’) to the industrialised north of England (with its belching smokestacks). In 1898, they set up their motherhouse at Mirfield in Yorkshire.

In 1902, the Bishop of Pretoria, William Marlborough Carter, had invited the Community of the Resurrection to establish a presence in the Transvaal. Early in 1903, three members of the Community (James Okey Nash, Latimer Fuller and Clement Thomson) had arrived here. They had taken up residence in a wood-and-corrugated-iron house at No. 10 Sherwell Street, Doornfontein. Their mandate was to do mission work among the multitude of African workers employed on the gold mines. In 1905, three more members of the Community came to Johannesburg; some of them were drawn into the affairs of the beleaguered St John’s College. Nash taught divinity, and assisted with the teaching of Latin, French and English.

In September 1905, the Archdeacon of Johannesburg and chairman of the Council of St John’s College, the Venerable Michael Furse, requested the Community of the Resurrection to assume control of the embattled little school. It was agreed that the Community would do so ‘for an experimental period of six months’ – it was to be a temporary ‘breathing space’ during which ‘more permanent arrangements’ would be made. Whether the Community would undertake longer-term responsibility for the school remained to be seen. Fr Clement Thomson CR wrote at the time that, before there could be ‘a good boys’ school run by the Community’ it would be necessary for the Community to ‘justify our venture of faith.’

It was on this provisional basis that these Anglo-Catholic brethren took charge of St John’s College in January 1906. As it transpired, they remained in charge for three decades, during which they, ‘for the love of God alone, rendered service which made possible the survival and extension’ of the College. Fr James Okey Nash CR became the Headmaster. Clement Thomson was his ‘chief assistant’ and, soon afterwards, Eustace Hill and Henry Alston joined them on the College staff. They were ‘men of high intellectual standing, and a devotion testified by the self-sacrifice of their lives.’ At the time, Bishop Carter articulated the College’s purpose as follows: ‘The College exists in order that there may be a school in Johannesburg where churchmen may have their boys brought up in a church atmosphere.’

Novelist and poet William Plomer, who attended St John’s from 1912 until 1914 and again in 1919-’20, later wrote in his memoirs that the Fathers of the Community of the Resurrection –

‘had an admirable purpose – to radiate, in the words of the School motto, lux, vita, caritas on the Transvaal highveld by means of education. They had also brought with them, of course, their High Churchery, which would at once have been evident to the trained eye on seeing the School badge, inscribed Collegium S. Johannis and adorned with an eagle who was scotching with his claw a snake twined round a chalice, and who bore in his beak, by way of identity card, a scroll with the words quem diligebat.’

By way of explanatory excursus: St John’s College was – for reasons that have long since vanished in the proverbial mists of time – named after St John the Evangelist, also known as St John the Apostle, the son of Zebedee and Salome, and the younger brother of the disciple James. In the Vulgate text of his Gospel, St John uses the words ‘quem diligebat’ on a recurring basis by way of third-person allusion to himself e.g. ‘discipulus ille quem diligebat Iesus’ and ‘illum discipulum quem diligebat Iesus’ – that disciple whom Jesus loved. For example, in John XIX xxvi we read: ‘Cum vidisset ergo Jesus matrem, et discipulum stantem, quem diligebat, dicit matri suae: Mulier, ecce filius tuus’: therefore, when Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing [at the foot of the cross] he said to his mother: woman, behold thy son. (This is the Biblical scene depicted atop the rood screen in the College’s memorial Chapel.)

St John is often symbolically represented by an eagle, a chalice and a serpent. According to legend, a pagan priest in Ephesus gave St John a chalice containing poisoned wine. When St John blessed the chalice, the venom was extracted from the concoction in the shape of a viper. The protective eagle then descended upon the serpent and neutralised it.

Plomer continued:

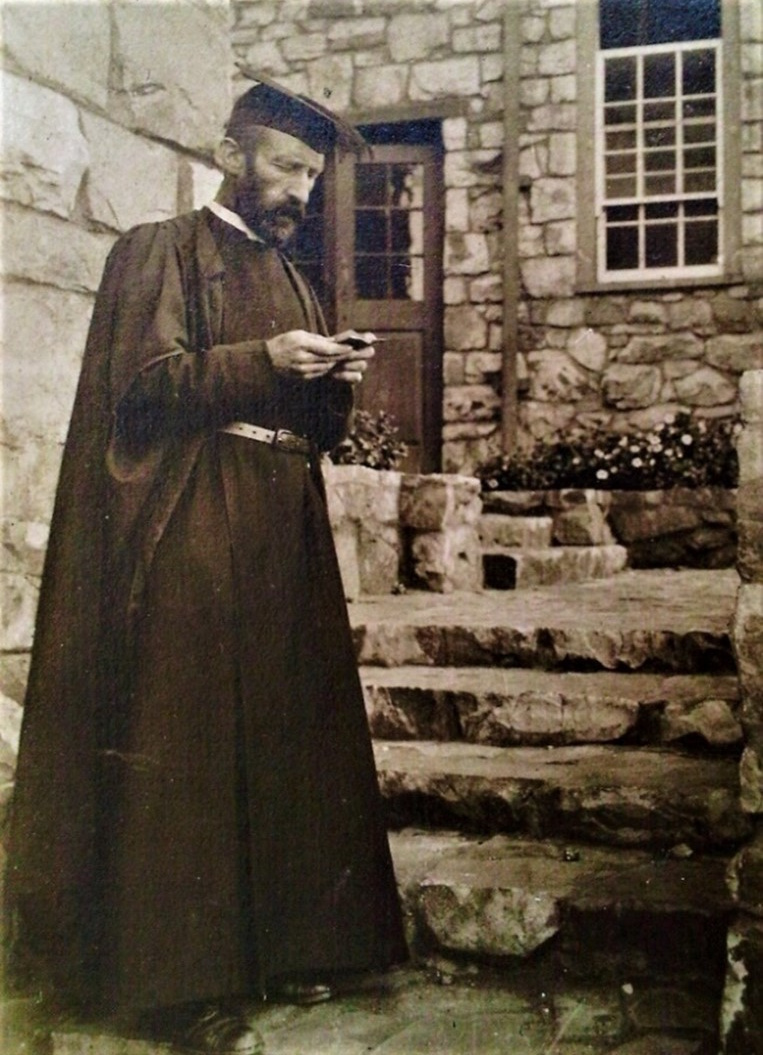

‘The fathers were mostly excellent creatures, late-Victorian Englishmen from Oxford and Cambridge, dedicated to a somewhat austere Anglo-Catholicism. Neither cranks nor fanatics – though one had a fierce, ascetic look like a half-starved bird of prey – they were mostly more like large good boys than school-masters. Their cassocks and birettas lent them an air of distinction. ... the religious instinct was given full play. A boy could enjoy and practise and believe in the Mirfield kind of religion without becoming mawkish or goody-goody.’

Apart from their work on the mines and at St John’s College, the brothers of the Community of the Resurrection took charge of the Sophiatown Native Mission and St Cyprian’s School (founded by John Darragh), attached to that mission. In 1904, the Community established St Peter’s Theological College in Rosettenville as a seminary for aspirant black Anglican clergymen. In 1908, the Community also started St Agnes’ School for African girls in Rosettenville. This was followed by the establishment of St Peter’s Secondary School for boys, also in Rosettenville, in 1922.

St Peter’s was the only boarding school for Africans in the Transvaal. The architect Frank Fleming (a contemporary at Denstone College in Staffordshire of Fr Osmund Victor CR, principal of St Peter’s Theological College from 1919-‘26,) designed some of the buildings. This contributed to the school’s ‘grandness of atmosphere’; it was known as a ‘Black Eton’. Its pupils went on to become prominent figures in the emerging black middle class; in the 1940s and 1950s they would become a who’s who in the African National Congress Youth League. Old Petrians included men such as Peter Abrahams, Fikile Bam, Jonas Gwangwa, Hugh Masekela, Todd Matshikiza, Joe Matthews, Congress Mbata, Zephania Mothopeng, Bertram Moloi, Es’kia Mphahlele, Duma Nokwe, Gerard Sekoto and Oliver Tambo. After having graduated from Fort Hare University College, Tambo returned to teach physics at St Peter’s (1943-’47).

St Cyprian’s and St Peter’s schools were closed in 1956 after the Bantu Education Act had made state funding of mission schools subject to acceptance of stringent conditions devised to promote apartheid policies. St Peter’s Theological College remained in existence; a young Desmond Tutu studied there, graduating in 1960.

In addition to these educational ventures, the Community of the Resurrection also ran St Augustine’s School at Penhalonga in Southern Rhodesia.

Because of the enduring connection between the Community of the Resurrection and St John’s College, the school later maintained an interest in the Sophiatown Mission and St Cyprian’s School for many years, even after the Community eventually resigned their charge of St John’s in 1935. St John’s boys made regular visits to the Ekutuleni Club at the Sophiatown Mission. The collection taken at the annual St John’s Carol Service was frequently earmarked for the Community’s work in Sophiatown and Orlando. There was also interaction between St John’s College and St Peter’s School.

Fr Trevor Huddleston CR (like Eustace Hill, an old boy of Lancing College in Sussex) ran the Sophiatown and Orlando missions in the 1940s and 1950s. He came to St John’s to speak about these missions, and took St John’s boys to Sophiatown and Orlando. In the 1950s he was a member of the College Council. In 1955, he spoke at the Congress of the People, where the Freedom Charter was adopted. In 1959, Fr Huddleston was involved in the founding of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, of which he was later elected president. He was consecrated Bishop of Masasi in Tanzania in 1960, where he remained until he became Bishop of Stepney and a suffragan bishop in the Diocese of London. He became Bishop of Mauritius in 1978, and shortly afterwards was made Archbishop of the Anglican Province of the Indian Ocean. In 1998, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II and chose the designation ‘Bishop Trevor of Sophiatown’.

In his 2008 MCC Spirit of Cricket Cowdrey Lecture, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu recounted how he, as a 15-year-old schoolboy in 1947, had become a cricket enthusiast:

‘I was living in the community of Sophiatown ... where Fr Trevor Huddleston and his celebrated brother monks from Yorkshire ministered. When I was diagnosed with tuberculosis, the fathers found me a hospital bed at Rietfontein on the eastern outskirts of Johannesburg, to which I was confined for 21 months. It was a long way from my home, public transport was not very good and my family couldn’t visit me very often, but a fellow patient ... introduced me to the cricket commentary on the radio for the first time. So John Arlott, with his distinctive voice and inimitable word pictures, drew me into the circle of international cricket sixty years ago.’

Thus the future Archbishop learned about cricket without ever having witnessed the contest between bat and ball. During the long months in hospital, Tutu received visits from C. R. brethren such as Huddleston, to whom he made his confessions, and Dominic Whitnall, who brought him books by Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, the great commentator on ‘Vanity Fair’.

All of this is background to the great ‘venture of faith’ that the Community of the Resurrection undertook at St John’s College.

The Revd James Okey Nash CR took office as Headmaster of St John’s College on 22 January 1906. He was an alumnus of King William’s College, Isle of Man, where he had been head of school and played in the 1st XI. He had then gone up to Hertford College, Oxford, where he obtained First Class Honours in Classical Moderations and Second Class Honours in Greats. After having spent some time in Paris, Nash went to Cuddesdon Theological College near Oxford. On Trinity Sunday in 1888 he was ordained by the Bishop of London, Frederick Temple (a former headmaster of Rugby School and later Archbishop of Canterbury) at St Paul’s Cathedral, and was entrusted with a curacy at St Andrew’s, Bethnal Green. In 1892, he became a founding member of the Community of the Resurrection.

As soon as he had taken office as Headmaster of St John’s, Nash reduced school fees to four guineas per quarter in the upper school and three guineas per quarter in the lower school. (Tuition fees in the upper school had been eight guineas per quarter in 1903. Fees in the lower school were now back to exactly the same level they had been in 1898.) However, despite this pecuniary incentive for boys to remain in, or return to, St John’s, the College roll in January 1906 listed the names of a pitiful 42 pupils. Apart from Nash himself, there were only three masters at the Tin Temple: Clement Thomson CR, Mr Anton Willem Rakers and Mr E Call-Weddell, who was in charge of the lower school. Barend Vieyra remained the gymnastics instructor. Leo Heath (organist of St Mary’s Church) was in charge of music, assisted by the Revd AH Trevor-Benson (precentor of St Mary’s). Accommodation for a few boarders was arranged at the Community’s residence in Sherwell Street, and meals (at a cost of 1 shilling each) were taken at a boarding house run by Mrs Mast, the widowed mother of a St John’s boy, at Rothesay Buildings on the corner of Kerk and Polly Streets. School hours were from nine o’ clock until noon, and then again from 1 p.m. until 3 p.m. (except on Wednesdays, when school ended at 2 p.m., presumably for games purposes).

From the outset Fr Nash kept a diary, meticulously recording daily events at the school. Providentially this diary has been preserved for posterity and so, to the extent that we can decipher Nash’s manuscript entries, we can determine exactly how he went about his business. In the first weeks of his administration, his actions ranged from the mundane (e.g. hanging up a bell and buying a cane) to the scholastically and ecclesiastically sublime (e.g. appointing a boy as hebdomadary to ring the bell and lead recitation of prayers, and introducing a system of weekly reports to parents and a system of daily detention for unsatisfactory work). He established a Games Committee and arranged for swimming (supervised by Fr Thomson) to take place at the Village Main Reef Dam.

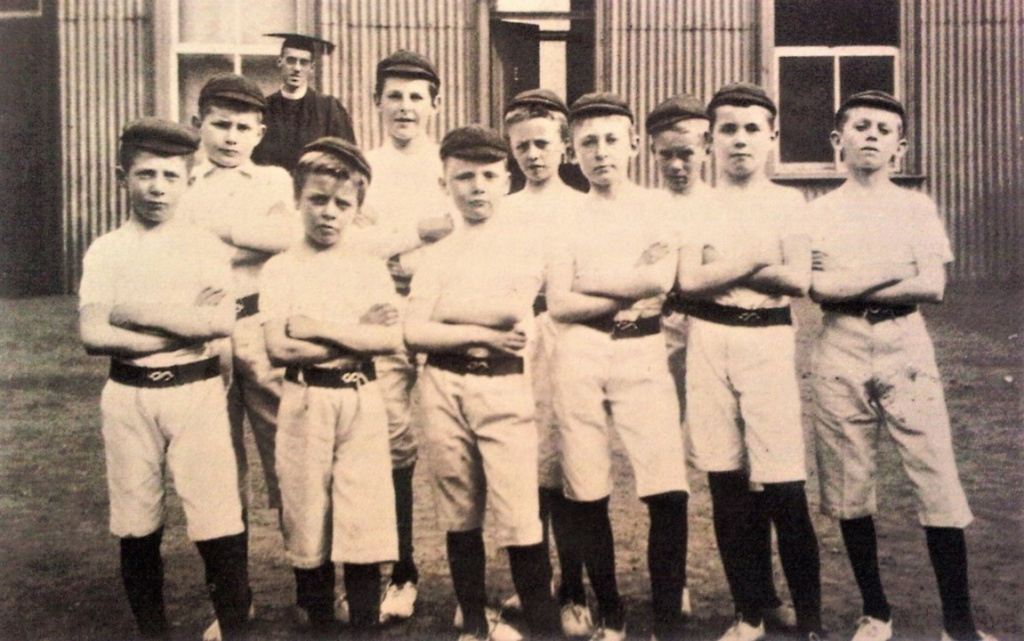

Fr Nash probably did not prioritise cricket as he set out to keep the ‘sinking ship’ that was St John’s College afloat on the ‘stormy seas’ that had nearly caused the school to perish. With only 42 boys in the school, and with cricket facilities limited to a single net in the Tin Temple’s backyard, the new Headmaster would not have been preoccupied with visions of a victorious cricket season. Still, net practices commenced immediately – a practice was held on the very first day of term, 22 January 1906 – and St John’s ambitiously entered two elevens in the schools league. Nevil Lindsay OJ initially coached the boys. (Lindsay had a long first-class career and played one Test match, against Australia in 1921. He was the great-uncle of Denis Lindsay, who played for South Africa in the 1960s.)

In 1906, the Transvaal Cricket Union started a system of engaging professional cricketers to provide coaching at schools. This scheme gave St John’s the benefit of the expertise of a proficient coach, who imparted his skills at the College net one afternoon per week, and encouraged St John’s to ‘plunge courageously into games.’ The first coach who came to St John’s as part of this scheme was a Mr Handford. In Fr Nash’s diary, he recorded the following on 31 January 1906: ‘Handford Cricket pro for net practices – order new mat & two bats.’

On 14 March, St John’s played against Johannesburg College (the predecessor of King Edward VII School). Fr Nash’s diary recorded the results: ‘Two games v Johannesburg College on their ground, postponed from Saturday 10th. Our 1st v Joh’g 2nd SJn 102 to Joh’g 76, 2nd v Joh’g 3rd SJn 74 to 130 6wkts.’ No doubt, after St John’s had sustained a drubbing at the hands of Johannesburg College’s 1st XI the previous year, it was now considered prudent to play against their 2nd XI.

On Thursday 15 March, the cricket team of the Pretoria Diocesan School for Boys (also known as St Birinus School, established by Bishop Bousfield in 1879) travelled to Johannesburg to play against St John’s. (In those days, the journey from Pretoria to Johannesburg and back would have been a time-consuming expedition.) St John’s batted first and scored 76. Pretoria made 64 in their first innings. The St John’s second innings was declared closed at 130/4, setting Pretoria a victory target of 143. Whether they were left insufficient time to score these runs before heading back to Park Station, or whether they simply shut up shop and played to protect their reputation, or whether rain interfered, we will never know, but Pretoria recorded 22/1 in their second innings. St John’s won the match on the first innings.

The principal of Pretoria Diocesan School was the Revd Henry Sidwell, who had been headmaster of St Mary’s School for Boys, founded by John Darragh in 1888, in the early 1890s. No doubt, over tea Sidwell regaled Nash with tales of life in Johannesburg fifteen years earlier, and reminisced about the fortunes of the school that was the progenitor of St John’s College.

On Friday 16 March, a Johannesburg Schools team played against Mr Abe Bailey’s XI. Two St John’s boys, Hugh Maxwell Hughes and Henry Thurston, were selected to play in the combined schools team.

The following day, the St John’s 1st XI played against St Mary’s, Rosettenville, at Turffontein. St John’s scored 98 and restricted Rosettenville to 86. On the same day, the 2nd XI played against St Augustine’s Choir School at Otto Square, Doornfontein. St John’s scored 47 and 67, while St Augustine’s scored 23 and 39, meaning that St John’s won by 52 runs.

The first matches between St John’s and Jeppe High School for Boys were played at the old Wanderers (just a few blocks away from the Tin Temple) on Tuesday 27 March. In the 1st XI game, Jeppe batted first and scored 52, which St John’s exceeded by scoring 97. Jeppe won the 2nd XI game by eight wickets. In the first match ever played by the St John’s 3rd XI, they scored 78, to which Jeppe replied with 116/3. Having regard to the fact that there were only forty-odd boys in the College at that stage, it is remarkable that it was possible to field a 3rd XI.

Meanwhile, Fr Nash was devising ways and means of securing the school’s survival, financially and otherwise. To this end, he persuaded the Inspector for Johannesburg and Rand schools, Mr FH Thompson, that St John’s College was an institution worth persevering with. This is reflected in a report that Thompson submitted to the Transvaal Education Department on 28 March 1906:

‘This school has seen many vicissitudes of recent years. A determined effort is now being made to render it thoroughly efficient. At present the school is suffering from the effects of past neglect, but there is every reason to believe that the staff at present engaged will succeed in restoring the school to a complete condition of efficiency. To do this it is necessary that sufficient means should be forthcoming to tide over the present year. I should strongly recommend that assistance be given for this purpose from the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Fund. The buildings are of wood and iron, provision is made for Elementary Science teaching and a well equipped gymnasium is in use. There are no boarders. The staff is quite capable of taking boys up to the Matriculation standard. The general tone and discipline of the school are excellent.’

Thompson’s report enclosed a copy of an earlier letter from Nash, in which the latter had highlighted ‘an important point touching on our financial position’: the fact that the Tin Temple stood on land owned by St Mary’s Church, which was almost certainly to be sold in order to fund the construction of a new church building – ‘Which means we shall have to get another site; and of course for this a block grant from the [Archbishop of Canterbury’s] fund would be a godsend.’

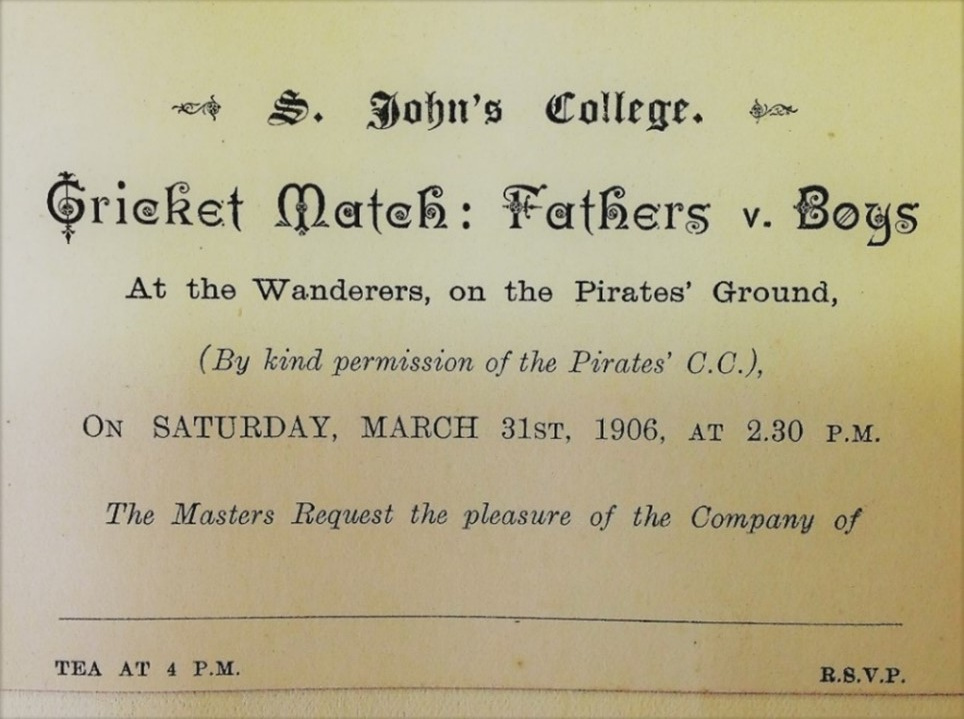

On Saturday 31 March, the first ‘Fathers v Boys’ cricket match was played, ‘in delightful weather’, at the Pirates ground. Mr Walter Greathead captained the Fathers’ XI, which also included Messrs Reid, Lindsay, Cooper, Thompson, King, Short, McKowen, Owen, Bell and the Revd Eustace Hill. The boys batted first and scored 128/7 declared (Thurston 39, Donovan 35*). The Fathers were dismissed for 81. Thurston took five wickets and Hughes four.

Despite the fact that St John’s College was still a very young school, a ‘Past v Present’ cricket match soon became an annual institution. The College’s initial match against the Old Johannians was played at the Wanderers on Thursday 5 April 1906. The encounter resulted in a trouncing for the schoolboys. The OJ XI comprised B Sims (captain), H Danziger, R Kearns, C Steed, G Vipan Theed, D de Sarigny, F McKowen, C Davis, R Marks, C Ogilvie and S Stokes. The College XI consisted of Thurston (captain), Hughes, Marais, Lewison, Donovan, Bell, Bisset, Reid, Morisse, Owen, Phipps-Hornby and Whiley. The boys batted first and were dismissed for 123, to which the OJs replied with 131/1. Thurston was, according to Fr Nash, ‘both a good bowler and a good bat’. Nash singled out Hughes as another good player. Marais was a fast bowler, and many of the ‘old “uns” had rueful recollections of receiving some nasty smacks in trying to play him.’

At a meeting of the Old Boys’ Association, the hat was passed round and members funded the purchase of a cricket bat and ball as prizes for the best batsman and bowler of the year among the College students; both prizes were awarded to H. G. Thurston (who was nicknamed ‘Toast’ on account of his smiling freckled face).

Meanwhile, events occurred in distant Zululand that portended the strife that would, in later decades, beset South Africa because of the oppression of her black peoples. As a mechanism for compelling black men to enter the formal job market, the Natal government had imposed a £1 poll tax on adult males. Due to resistance to the imposition of this tax, the government proclaimed martial law and a dozen rebels were summarily executed. A minor chief of the amaZondi tribe, Bambatha, refused to collect the poll tax from his subjects, as a result of which he was deposed by the authorities. In April 1906, Bambatha and his men ambushed a police contingent and killed four officers.

With general lawlessness erupting in northern Natal, a large militia set out against Bambatha and his followers. On 9 June 1906, Bambatha and his men were trapped and massacred, some 600 men being killed. Bambatha’s body was decapitated. Several chiefs continued resistance in the lower Thukela area until July, but the uprising was suppressed. In total, about 3,000 dissidents were killed during the rebellion, and about 7,000 were arrested and imprisoned. One of the chaplains to the punitive expedition was Fr Eustace Hill. After the campaign, he returned his medals to the military authorities because he thought the action had been unjust and cruel.

As we have seen, in 1904 Johannesburg College had moved from Kerk Street to the Barnato mansion in Berea. The contrast between these manorial premises and the humble Tin Temple, which was then home to St John’s College, could hardly have been more pronounced. However, Barnato House was merely a way station for Johannesburg College, to be occupied temporarily until even better premises could be found for what was intended by the Transvaal Education Department to be the flagship ‘Milner school’.

The location of the new premises was a matter of great moment. Three possibilities were being considered: sites in Braamfontein, in Houghton Estate, and in Smit Street in central Johannesburg. In October 1905, the Lieutenant-Governor of the Transvaal, Sir Arthur Lawley, had set up a commission to consider and make recommendations in this regard. The Secondary Education Commission was chaired by the Director of Education, John Adamson, and its members included Sir William Carr, Sir Percy FitzPatrick and the Venerable Michael Furse (Archdeacon of Johannesburg and chairman of the Council of St John’s College), as well as several members of the non-governmental Witwatersrand Council of Education (WCE). The Commission’s terms of reference included the question where government schools should be placed so as to serve most adequately the needs of the population.

The Commission received evidence from more than thirty witnesses. It appeared that, at the end of 1905, Johannesburg College had about 150 pupils. Its principal, Mr JM Crofts, was of the view that the optimal site for that school would be on the Houghton Estate, not far from Barnato Park. One member of Johannesburg College’s governing body, Mr RT Smith, was of the same view, despite the fact that the Braamfontein site could be obtained free of charge while an amount of £9,600 would have to be expended for the Houghton site. By contrast, another member of the governing body, Mr CF Tainton, believed that the Braamfontein location was ‘ideal’. The evidence also indicated that, when Johannesburg College was originally started, St John’s had lost about sixty boys to the new school due to the fact that the latter charged only nominal fees. St John’s now had only fifty pupils. Marist Brothers’ College had 530 pupils (as compared to 750 immediately before the Anglo-Boer War).

Upon conclusion of its proceedings at the end of 1905, the Commission recommended that new school buildings be erected in Malvern for Jeppe High School, and for Johannesburg College on a four-acre site in Smit Street overlooking the old Wanderers. But the Commission’s recommendation regarding the location of the Johannesburg College premises was not the final word on the matter. Even before the Commission had published its findings, news of its conclusions had been leaked. There was a ‘roar of protest’ from the Johannesburg College lobby group that opposed the Smit Street site: ‘The [Johannesburg] College had many friends and there were many influential people among its parents. They all now rose in their wrath and said, metaphorically: “Over our dead bodies”.’

Apart from the fact that the Smit Street site was not the preferred location of Johannesburg College itself, the development of the new site was dependent, to an extent, upon funding from the WCE, which had been asked to contribute £12,500 for that purpose. This the WCE declined to do, rejecting the Smit Street site as ‘altogether unsuitable’. Protracted discussions ensued during which the government urged the merits of the Smit Street site, but the WCE refused to budge. Braamfontein Estate Company offered alternative sites in Westcliff and Saxonwold, but these were also rejected by the WCE. The governing body of Johannesburg College was adamant in its preference for the site in Houghton Estate. The difficulty – and it was one that would generate much controversy and acrimony – was that Fr James Okey Nash had already identified Houghton as the preferred location for the construction of new buildings for St John’s College.

Nash had conceived an ambitious vision for the development of St John’s – one that was far removed from the Tin Temple in geographic location, and even further in terms of its grandiose scope. The Tin Temple (quite apart from being woefully lacking in amenities) was unsuitable, being situated adjacent to the drill ground and with no room for future expansion. So, early in April 1906, Nash and Archdeacon Furse, setting out on horseback, had conducted inspections of possible alternative sites. These equestrian excursions had resulted in Nash developing a preference for the rustic site on the Houghton Estate.

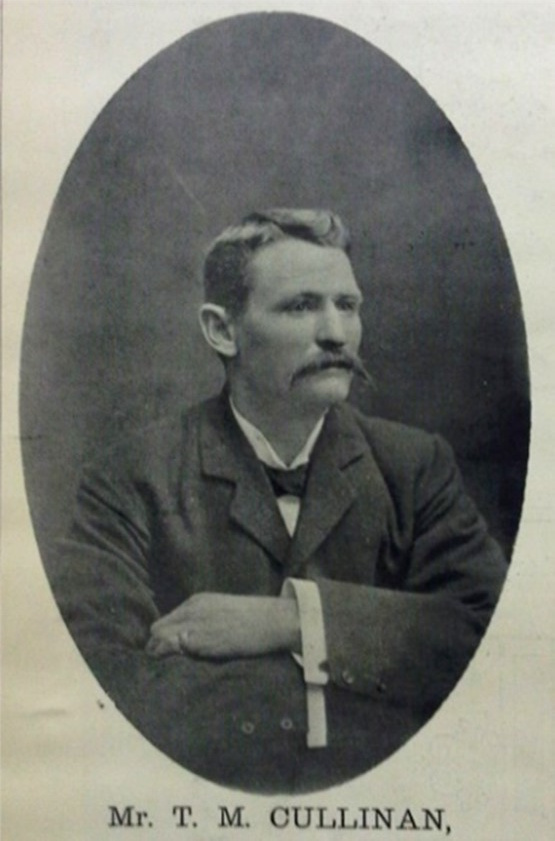

However, the implementation of Nash’s scheme required a degree of funding that seemed to render the scheme a castle in the air. Men endowed with less imagination and faith would have abandoned the plan as fanciful. But the dream acquired a glimmer of potential reality when the diamond magnate Thomas Cullinan donated £5,000 towards its fulfilment. Now, Nash could enter into negotiations with Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Company, which owned the site he had identified as the setting for the St John’s College of the future: a large area of kopje and grassland in the Houghton Estate, contiguous to the golf course north of Morgan Road (now Louis Botha Avenue).

On 3 July 1906, Nash met with JCI’s managing director. Furse then made a written offer to JCI: to buy three or four acres for £2,500, which would leave an equal amount to be used for construction purposes. On 27 July, JCI wrote to Furse, confirming that it would extend to St John’s ‘the same offer for a school site on the Houghton Estate as was made to the Johannesburg College and refused by that body.’ On 17 August, Nash was informed that JCI was willing to sell four acres to St John’s for £2,500 – and give a further four acres to the school in freehold.

By then, Nash had already had discussions with the young architect Herbert Baker, who was now instructed to draft plans for the new buildings. These plans were approved by the Diocesan Board on 19 November. Five days later, Nash announced the news of the proposed development to a gathering at the school’s gymnastics championships. The site was ‘exceedingly healthy in its position’, he said, ‘and had a good view.’ He thought the boys would appreciate the fact that the site included ‘a splendid piece of level ground suitable for a football and cricket field.’ He said that Mr Baker was the architect appointed to design the new building, and he expressed the hope that construction would begin ‘before very long.’

Meanwhile, by mid-1906 St John’s had 60 boys in regular attendance – a slight increase on the 42 who had been present at the beginning of the year. At the end of June, to conclude Easter Term, the school staged scenes from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, funded partly from a contribution towards a planned cricket excursion that had fallen through. Henry Thurston appeared as Duke Frederick; James Bell was Rosalind; Hugh Hughes was Orlando; Oswald Reid was Le Beau; and Bennett Donovan was the Banished Duke. The programme also included a number of sung items (including ‘Here’s a health unto his Majesty’ and ‘Blue Bells of Scotland’), with Messrs Heath and Call-Weddell as accompanists.

At the beginning of Trinity Term, on Tuesday 7 August, eight new boys enrolled; but six had departed at the end of Easter Term. So, in terms of numbers, it was a case of two steps forward, one step back. On the whole, though, the trend was forward and upward: three further new boys arrived during the course of the next week, and another four at the beginning of September.

The second annual Transvaal Inter High School Athletic Sports were held at the Wanderers in ‘fine but windy’ weather on 19 September, under the patronage of His Excellency the Earl of Selborne (who had succeeded Viscount Milner as High Commissioner for Southern Africa). Eight schools participated: Pretoria Diocesan School; Eendracht School (the eventual winners); Jeppes High School; Jeppes Institute; Johannesburg College; Pretoria College; St John’s College (colours: dark blue and maroon); and Marist Brothers’ College. St John’s finished fourth in the contest. Henry Thurston won the silver medal in the senior half-mile race and bronze in the mile.

At the beginning of Advent Term, the Transvaal Cricket Union appointed Mr Alfred Atfield (1868-1949) as cricket coach for St John’s College and Jeppe High School. The generosity of Mr Abe Bailey, who gave £500 to the TCU to provide a coach for the schools, enabled the College 1st XI to be coached by Mr Atfield twice a week. He made his first appearance at the St John’s net on Wednesday 10 October. He had previously played for Gloucestershire, London County, MCC and Natal, and held the distinction of having dismissed WG Grace in a match between MCC and London County in 1901. (Atfield was married in 1901; the wedding took place in the morning and that same afternoon he scored 121* at Lord’s.) He would make a solitary appearance for Transvaal in 1907 before becoming a first-class and Test umpire. His umpiring experience included officiating in the Actors v Authors match at Lord’s in 1905; the players in that game included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, PG Wodehouse, C Aubrey Smith (a former Sussex player and later Hollywood actor) and Gerald du Maurier.

Mr William Rockey, a parishioner of St Mary’s Church and a member of the College Council, donated a new cricket mat, turf pitches being foreign to the Transvaal in those days. (The innovation of turf pitches only reached the Transvaal in the 1930s.)

On Wednesday 24 October, St John’s played against St Mary’s, Rosettenville, at Turffontein. St Mary’s scored 89 (Thurston 6/12). St John’s made 73 (Donovan 26, Hughes 22). On Saturday 27 October, the 2nd XI played against the Revd Mr Carter’s XI at Norwood. In the first innings, Carter’s XI scored 26, to which St John’s replied with 34. The Revd Carter made a generous declaration in the second innings, setting St John’s a target of 36, which was reached without the loss of any wickets.

On the afternoon of Monday 29 October, the College 1st XI played against a Clergy XI at the Wanderers ‘in charming weather’. Fr Nash turned out for the College, scoring seven runs. St John’s made 116 (Thurston 30, extras 21) in 2¾ hours, leaving the men of the cloth only 45 minutes in which to bat. The clergymen took every risk conceivable in their attempt to reach the target but, at six o’ clock, when stumps were to be drawn, they were still a few runs behind but had lost only one wicket. The boys consented to remain in the field and not earn an unenviable draw. This enabled the Clergy XI to win by nine wickets.

Newspaper reports on the match commented adversely on the boys’ fielding (‘their greatest fault lay in the matter of missed catches, which were quite numerous’). Fr Nash read the reports to the boys the next day, and subjected them to strenuous fielding practice. ‘Before the end of term,’ he said, ‘our fielding was two or three times well spoken of.’

On 31 October, the College 1st XI lost to Johannesburg College 2nd XI by 25 runs. The 2nd XI had better fortunes, beating St Augustine’s Choir School by 50 runs on 3 November and Johannesburg College 3rd XI by 29 runs four days later.

On Thursday 8 November (the day before the birthday of His Majesty, King Edward VII, which was a public holiday), the 1st XI played against Jeppe at the Wanderers. St John’s were in trouble at 39/6 but reached 109, thanks to a 36-run partnership for the ninth wicket between Oswald Reid (44) and Ronald (‘Gogs’) Owen (15*). Jeppe were dismissed for 86 (Thurston 8/31). The two schools’ 2nd XIs met on 12 November, St John’s winning by four wickets. Roseveare scored 63 in the St John’s total of 96/6.

Thurston and Hughes played for the Johannesburg Schools XVIII against Mr Abe Bailey’s XI at the Wanderers on 13 November. Two days later, St John’s played against Turffontein at the Wemmer ground. It was ‘no game’, wrote Fr Nash in his diary, St John’s scoring 92 and dismissing Turffontein for 40. But the tables were turned a few weeks later, when Turffontein won the return match by 32 runs. The St John’s junior team lost to Johannesburg College on 17 November, but beat Park Town School on 21 November, scoring 29 and 40 compared to their opponents’ totals of 21 and 30.

St John’s prevailed over Pretoria Diocesan School, the match being played at Pretoria on Wednesday 28 November. St John’s scored 240, to which the captain, Thurston, contributed a fine and almost flawless 151. Pretoria were dismissed for 86 in their first innings. Following on, they were all out for 51. Thurston, who had not bowled in the first innings, took 7/23 in the second, thus completing a remarkable double. Hughes took 3/22. St John’s won by an innings and 103 runs.

Meanwhile, on 24 November the school’s gymnastics championships were held. Bennett Donovan was named the champion and was to receive a medal donated by the legendary instructor Mr Vieyra. It was at the same occasion that Fr Nash announced the College’s planned relocation to Houghton.

On Monday 3 December, St John’s played against Marist Brothers’ College at the Wanderers. St John’s scored 138 (Thurston 37). At stumps, Marists had 62/4, the match ending in a draw. The 3rd XI beat their counterparts from Jeppe by five runs on 6 December.

In the match against the Parents’ XI, Thurston and Hughes made a first-wicket stand of 51 runs. The boys then dismissed their fathers quickly and won by 43 runs. (In 1907, Thurston and his parents were to emigrate to the United States of America ‘where, unhappy nation! they have no cricket,’ commented Fr Nash. Thurston became captain of the ‘track team’ at Cascadilla School, Ithaca, NY.)

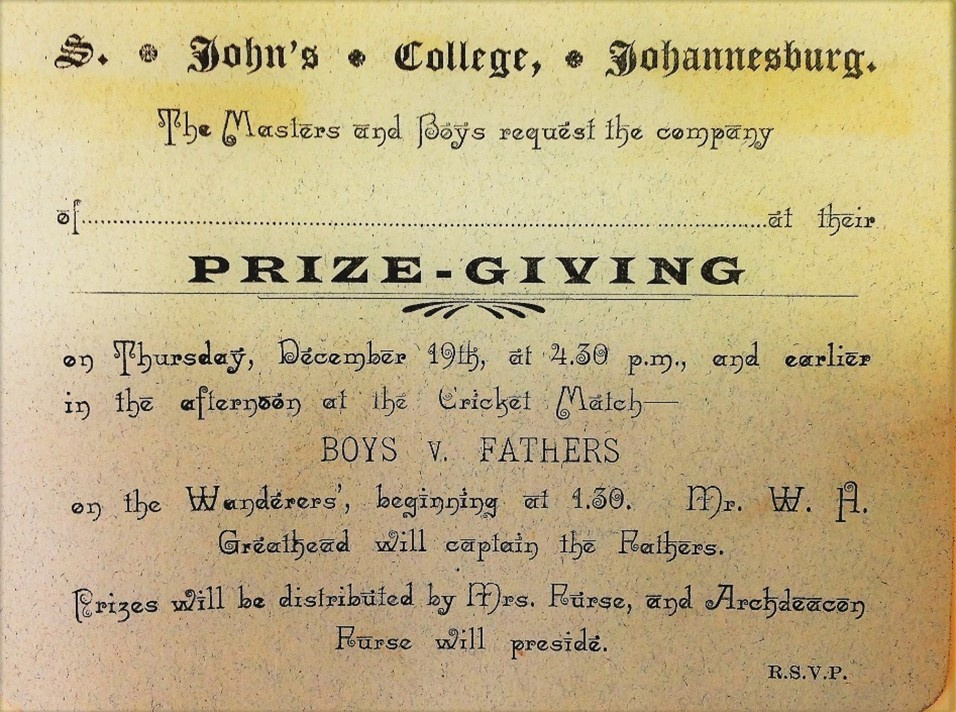

At the prize-giving on St Thomas’ Day, 21 December 1906, the book prizes were adorned for the first time with the ‘new stamp of the Eagle of S. John, a copy admirably made by a London firm from the shield painted for S. John’s by Mr AN Foord, in England.’ In his address, Fr Nash articulated his opposition to the proposed new site for Johannesburg College, in close proximity to the Houghton site identified for St John’s. He spoke ‘in the plainest terms’ of an impending danger: ‘Schools could be very good friends, but make most uncomfortable bedfellows. We are good friends with Johannesburg College, and meet cordially in the cricket and football fields. We have taken our lickings in cricket and football, and have now and then enjoyed the satisfaction of a brotherly revenge. But such an arrangement as [is] proposed would be continuously and increasingly painful to both schools.’

In the Johannesburg College corridors, Nash’s speech was regarded as ‘exceptionally tactless’ and as containing a ‘great deal [of] arrant nonsense ... the uncharitableness (sic) of which was no credit to either Nash or St John’s.’ It served only to ‘stiffen the resolve of the parents and masters of the Johannesburg College in the battle that was to come.’

On the same day as the prize-giving, a Parents v Sons cricket match was played at the Wanderers. The parents scored 115/8 (Mr Greathead 61*), after which the boys lost four wickets cheaply before Jim Bell (21) and Ronals Owen took the score to 66/5, the game being drawn.

At the end of 1906, Fr Nash (who already held an MA degree from Oxford University) was admitted to the same degree by the University of the Cape of Good Hope.

Principal sources:

CR Diamond Jubilee Book (1952); Report of the Secondary Education (Johannesburg) Commission (1906); Agar-Hamilton Transvaal Jubilee: A History of the Church of the Province of South Africa in the Transvaal (1928); Allen Rabble-Rouser for Peace: The Authorised Biography of Desmond Tutu (2006); Callinicos Oliver Tambo: Beyond the Engeli Mountains (2004); Cartwright Strenue – The Story of King Edward VII School (1974); Christopher King William’s College Register (1905); Eccles & Simon ‘The Community of the Resurrection’ in Jonveaux & Palmisano (eds) Monasticism in Modern Times (2016); Hanbury OSB ‘Br James, Oblate OSB (Eustace St Clair Hill, 1873-1953)’ Pax 1953; Huddleston Naught for Your Comfort (1956); Lawson Venture of Faith: The Story of St John’s College, Johannesburg (1968); Macfarlane Greater Than We Know: The History of St John’s Preparatory School (2004); Malan Cheesecutters & Gymslips: South Africans at Boarding School (2008); Mosley The Life of Raymond Raynes (1963); Mphahlele Down Second Avenue (1959); Neame City Built on Gold (1960); Paton Apartheid & the Archbishop: The Life & Times of Geoffrey Clayton (1973); Plomer Double Lives: An Autobiography (1943); Plomer The South African Autobiography (1984); Skota The African Yearly Register, Being an Illustrated National Biographical (Who’s Who) of Black Folks in Africa (1932); Suberg The Anglican Tradition in South Africa: A Historical Overview (1999); Sundkler & Steed A History of the Church in Africa (2000); Wilkinson The Community of the Resurrection: A Centenary History (1992); Venter ‘Die groei van onderwysaangeleenthede in Johannesburg, 1886-1920’ (PhD thesis, Potchefstroom University, 1950); Winter Till Darkness Fell (1962); Winterbach ‘The Community of the Resurrection’s involvement in African schooling on the Witwatersrand, from 1903 to 1956’ (M Ed dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, 1994); Woeber ‘”A Good Education Sets Up a Divine Discontent”: The Contribution of St Peter’s School to Black South African Autobiography’ (PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 2000)

The Guardian 30 May 1888 790; Transvaal Leader 5 April 1906, 6 April 1906, 20 September 1906, 30 October 1906, 1 December 1906, 5 December 1906, 22 December 1906; Rand Daily Mail 30 October 1906, 13 November 1906, 14 November 1906, 26 November 1906, 22 December 1906; The Star 20 September 1906, 26 November 1906

St John’s College Letter of Trinity & Advent Terms 1906; The Johannian Michaelmas 1921, Michaelmas 1923, December 1936, October 1942, September 1943, September 1944, April 1946, October 1952, November 1953, May 1955, November 1975, 1982, 1993