1900 – 1901: ‘Whose hill? What for?’

One of the most distinguished Old Johannians from the early decades of the College’s existence was William Plomer. Born in 1903, he attended St John’s from 1912 until 1914. During the First World War, he went to Rugby School in Warwickshire. After the War, he returned to St John’s, winning the Form V prizes for Latin and French in 1920. In the ensuing decades, Plomer achieved prominence as an author. His prose fiction included his debut novel Turbott Wolfe, written when he was 19 years old and published a few years later, in 1925. It provoked a hullabaloo in white South African society because it touched on themes of interracial love and questioned the supposed benevolence of whites toward black people. Plomer worked with the poet Roy Campbell and Laurens van der Post in producing the avant-garde literary magazine Voorslag, which criticised racial prejudice in South Africa. He wrote the novellas Portraits in the Nude (1926) and Ula Masondo (1927), and a memoir called Museum Pieces (1952). He also published several volumes of poetry and short stories, and a searching biography of Cecil John Rhodes (1933). During World War II, he served in the British Naval Intelligence Division. He was the librettist to three of composer Benjamin Britten’s operatic and choral works, including Gloriana, commissioned for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II (1953). He ‘discovered’ Ian Fleming’s James Bond: while working as a literary editor for the publishing house Jonathan Cape, he recommended publication of the first book in the series, Casino Royale. He edited several subsequent Bond novels. The University of Durham conferred an honorary doctorate in literature on Plomer in 1959, and in 1968 Queen Elizabeth II bestowed the status of Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) on him.

We mention Plomer here because, many years after the Anglo-Boer South African War, he wrote a well-known poem that evocatively reflected on an aspect of the conflict and its lasting impact:

‘The whip-crack of a Union Jack

In a stiff breeze (the ship will roll),

Deft abracadabra drums

Enchant the patriotic soul –

A grandsire in St James’s Street

Sat at the window of his club.

His second son, shot through the throat,

Slid backwards down a slope of scrub,

Gargled his last breaths, one by one by one,

In too much blood, too young to spill,

Died difficultly, drop by drop by drop –

‘By your son’s courage, sir, we took the hill.’

They took the hill (Whose hill? What for?)

But what a climb they left to do!

Out of that bungled, unwise war

An alp of unforgiveness grew.

We have seen that, even before the Anglo-Boer South African War had begun in October 1899, many residents of Johannesburg had departed from the city in an endeavour to escape the approaching hostilities. In the following months, many more civilians joined the quest for the relative safety of the Cape Colony and Natal. Kenneth Lawson’s splendid history of the College, Venture of Faith, suggests that the Headmaster, the Revd Mr Hodgson, was swept away in the initial flood of refugees. In fact, however, Hodgson remained in Johannesburg until March 1900, when he eventually departed from the Transvaal under threat of deportation by the Boer authorities, presumably on account of his pro-British sympathies, real or perceived.

By contrast, the Revd Mr Darragh (who, as an Irishman, was a citizen of a neutral power) was permitted to remain in Johannesburg and to continue his parish work. He acted as headmaster of St John’s for a while but he, too, eventually joined the evacuation. Mr Alexander Benson, a solicitor and parishioner of St Mary’s Church, then stepped in as solitary teacher at St John’s. He has been described as ‘a warm but at times irascible character’ with ‘a passionate belief in the proper use and elocution of the English language.’

Although numbers at morning roll call were dwindling, a new boy (Russell St Leger Attwell) was enrolled on 23 April 1900, seven months after the War had started. As such, the school proved resilient in the face of socio-political tumult.

On 22 May 1900, the commander-in-chief of the British forces, Lord Roberts, moved his main army forward from Kroonstad, poised to invade the Transvaal. Two days later, the Cavalry Division, under General Sir John French, crossed the Vaal and deployed north of the river. With flanks and front thus protected, the British army forded the Vaal at Vereeniging, the target being Pretoria via Johannesburg.

News of these manoeuvres filtered through to Johannesburg. To Mr Benson, this was a signal to close the school. Accordingly, when the few remaining boys arrived at school one morning towards the end of May 1900, they found no master: during the night, Mr Benson had cycled south to join the British forces. He had heard that he was about to be arrested due to his pro-British sentiments. Thus the remaining College boys –probably not overwhelmed by grief – were left bereft of their school.

Incidentally, Mr Benson’s son, Henry, later received his early education at St John’s Preparatory School. Miss Thomas, a firm disciplinarian, drummed into young Henry the need always to attain the highest possible standard. He eventually became senior partner of the London office of the auditing firm Coopers & Lybrand (today part of PwC), a colonel in the Special Operations Executive during World War II, advisor to the Bank of England, and chairman of the Royal Commission on Legal Services, and was made a life peer in 1981. His obituary in The Times stated that ‘few men outside Whitehall can have had more influence on postwar Britain.’

In the circumstances described above, the Anglo-Boer South African War eventually necessitated the closure of St John’s College. The story of the College might very well have ended there, less than two years after the school had enrolled her initial pupils. With Johannesburg derelict and the country at war, not many people would have held out much hope of the school somehow remaining in existence.

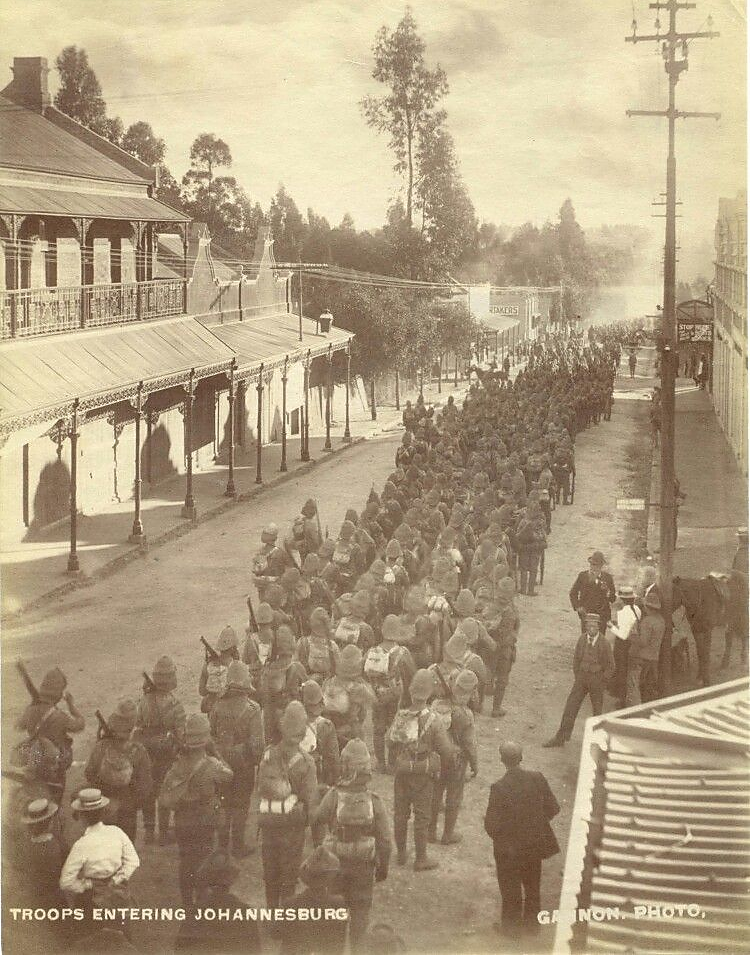

On 31 May 1900, the British forces took control of Johannesburg. The occasion was marked by the formal hoisting of the Union Jack at the Magistrates’ Court. A few St John’s boys went to witness the ceremony. They had the pleasure of welcoming Mr Benson and the Revd Mr Darragh, who arrived on a mule wagon in the British army convoy (somehow having contrived to have himself appointed as a chaplain to the British forces).

On 5 June 1900, the Z. A. R. government abandoned their capital, Pretoria, which was taken by the British without any shots having to be fired. The British army’s triumphal march into Pretoria had an anti-climactic, if not artificial, air.

Although Pretoria was not ablaze, the British forces’ unimpeded capture of the Boer capital perhaps reminded Lord Roberts of Napoleon’s ill-fated arrival in Moscow in 1812; there were uncanny parallels between the Boers’ surrender-and-retreat tactics and those that had been adopted by General Kutuzov as he lured Napoleon into the Russian heartland. If Roberts was mindful of these similarities, he did not let on. Whatever private apprehensions he may have harboured, publicly he asserted that only ‘mopping-up’ operations remained. In December 1900 he announced that the War was ‘practically over’.

Despite Roberts’ assurances to Queen Victoria that victory was imminent, she would not live to see the end of the War: she passed away on 22 January 1901, having reigned for 63 years. Despite the British implementation of a devastating scorched-earth policy and the internment and death of tens of thousands of non-combatant civilians – black and white – in concentration camps, the Boer guerrillas would remain unvanquished until May 1902. It would prove to be the most protracted, costliest and bloodiest war fought by Great Britain for a century. By 1901, it was costing Her Majesty’s Treasury £140 – the equivalent of the price of a ton of bullets – to eliminate a single Boer combatant. The war cost the British taxpayer £200 million. Some 22,000 imperial soldiers were killed: about 6,000 perished in combat, while 16,000 died of wounds or succumbed to disease. The War Office estimated that 400,346 horses, mules and donkeys were ‘expended’ in the war.

Once the Union Jack was flying over the Witwatersrand in mid-1900, many civilians returned to Johannesburg. One of Darragh’s earliest preoccupations was to reopen St John’s College. The available sources are inconsistent as to exactly when and how this ambition of his was achieved. According to the official school history, the school had been closed ‘for nearly two years’. Eric Thompson’s history of the Old Johannian Association says that the school had been closed for about nineteen months. On these accounts, and on the basis that the school’s activities had been terminated upon Benson’s departure in May 1900, that would mean that there must have been a hiatus in the school’s history until at least January 1902.

However, it appears that the school was, in fact, revived sooner than that. Already in November 1900, Hodgson (who had, in the interim, returned to England) received a cablegram (probably from Darragh) requesting him to return to Johannesburg in order to reopen the school. (This version has the ring of truth: why would Darragh, who returned to Johannesburg at the end of May 1900, sit on his hands?) Hodgson was happy to oblige and sailed to Durban, where he arrived in January 1901. However, on account of the continuing hostilities he had to wait until March before he was granted a permit to travel into the interior. Eventually, in April 1901, Hodgson managed to resuscitate the school, in the Hanau villa in Plein Street.

History displayed its propensity for repeating – or at least approximating – itself. In August 1898, when St John’s College had first opened her doors, six boys had enrolled on the first day, followed by a further five the following day. Now, in April 1901, five boys turned up on the opening day, and six more were enrolled the next morning. (In both instances, by the second day the school had enough boys for a cricket XI or a football team!) A week later, two more boys joined. The boys were supplied with the College colours, comprising a blazer, cap, hat-band and silk scarf, the school colours being salmon pink on a chocolate background, in alternate stripes of broad chocolate and narrow pink.

In the months that followed, enrolment continued to increase gradually such that, by the end of 1901, there were fifty boys in the school. Hodgson was soon joined by Mr Anton Willem Rakers (a Hollander who taught Dutch, French and German, and also mathematics and science), so that there were two full-time masters. Teaching assistance was provided by two army chaplains, Messrs McPherson and Heathcot. A Mr Kernick taught occasionally, as did the famous gymnastics instructor, Mr Barend Vieyra, who would remain with the school for many years.

Although still very much in her infancy, St John’s College had already experienced remarkable fluctuations of fortune. From having started its existence with fewer than a dozen boys, the school had soon flourished to have an enrolment in excess of a hundred boys when the Anglo-Boer War and the British occupation of Johannesburg had intervened and necessitated the school’s closure. The school had then started again from scratch, and soon acquired a new lease of life.

The fact that the school’s roll was slowly expanding, despite the privations and vicissitudes of the continuing war, provided grounds for hope that the fledgling Anglican boys’ school of Johannesburg would flourish again. Indeed, optimistic men on the St Mary’s parochial council found these signs so encouraging that, planning for the bright future which they believed awaited the school, they again began to explore possibilities for larger premises – and not without reason, for prospects did look as rosy as the stripes in the school colours. But the College’s fluctuations in fortune were destined to continue.

Principal sources:

Agar-Hamilton Transvaal Jubilee: A History of the Church of the Province of South Africa in the Transvaal (1968); Lawson Venture of Faith (1968); Kruger Goodbye Dolly Gray (1959); Macfarlane Greater Than We Know (2004); Meredith Diamonds, Gold & War (2007); Nasson The War for South Africa (2010); Neame City Built on Gold (1960); Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004); Pakenham The Boer War (1979); Thompson OJ Let Me Tell You: The Story of the First 73 Years of the Old Johannian Association (1976); Venter ‘Die groei van onderwysaangeleenthede in Johannesburg, 1886-1920’; Encyclopaedia Brittanica s.v. “William Plomer”; Rand Daily Mail 23 December 1902; The Star 22 December 1902 and 4 May 1935; The Independent 13 March 1995; The Johannian December 1934, September 1943, February 1982