by Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

‘A sound secular and religious education on definite Church of England principles’

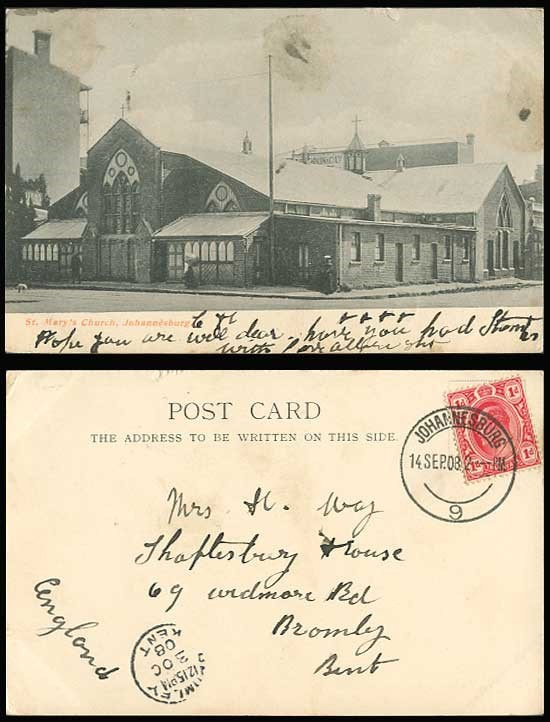

The dismal state of educational affairs in fin-de-siècle Johannesburg – the town had only one reputable school for boys, namely Marist Brothers’ College – induced clergymen and parishioners of St Mary’s Anglican Church to devise plans for the establishment of a new boys’ school.

Kenneth Lawson explains in his magisterial account of the provenance of St John’s College, Venture of Faith (1968), that the chain of events that eventually culminated in the founding of the school was set in motion by the inaugural Anglican Bishop of Pretoria, the Rt Revd Henry Brougham Bousfield (1832-1902). Educated at Merchant Taylors’ School and Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge (where he was exhibitioner and graduated as junior optime), Bousfield had been consecrated Bishop of Pretoria at St Paul’s Cathedral in London on 2 February 1878 before sailing to Durban. From there he trekked to Pretoria ‘with a full entourage including his wife, children, clergy, some schoolteachers and a mistress.’ The 400-mile journey from the coast was ‘peculiarly trying’: half the oxen died from lack of food and from disease, and for two months the Bishop’s party had to live in tents. Driven by a conviction that neither Catholics nor Methodists were Christians, with the result that ‘he feared for the eternal soul of any Anglican who might begin worshipping with them in some remote and unAnglicanized corner of the high veld,’ he embarked on a ‘heroic peripatetic ministry.’

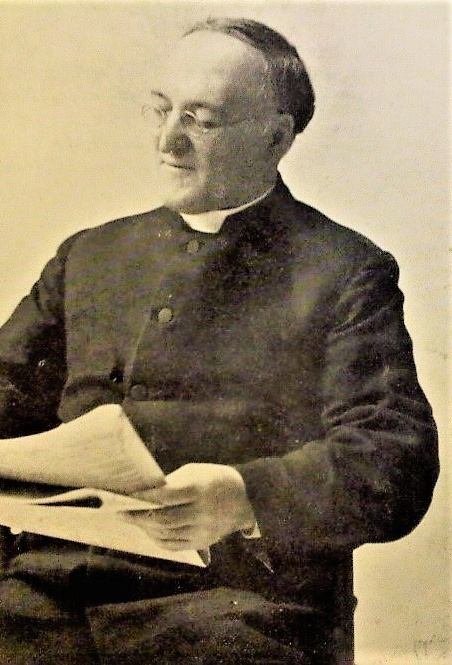

Shortly after the inception of the gold rush in 1886, Bousfield travelled from Pretoria to the Witwatersrand to assess the spiritual needs of the growing English-speaking community in the new settlement. His inspection in loco impressed upon him that a priest of exceptional qualities would be required to minister to the pastoral needs of the Gold Fields community. He recruited a feisty young Irishman, the Revd John Thomas Darragh (1853-1922), then curate of the Kimberley Diamond Fields. Within a fortnight of Darragh’s arrival in Johannesburg in 1887, the foundation stone of St Mary’s Church, a red-brick structure situated on the south-west corner of Eloff and Kerk Streets, was laid. (Bousfield, who frequently did not see eye to eye with Darragh, later described that St Mary’s edifice as ‘a brick oven with an iron roof’. Of course, the present St Mary’s Cathedral, designed by Frank Fleming and constructed in 1929, by no means answers to that description.)

A year later, in 1888, Darragh founded St Mary’s College for Girls. He arranged for Miss Mary Ross to come out from Somerset to teach at St Mary’s. Fearing that some eligible bachelor would snap her up in a trice for nuptial purposes – as invariably happened to attractive young women who arrived on the Rand – and that he would then have to find a new schoolmistress, he required her to undertake that she would not marry within three years. Within three months, he married her himself.

Darragh featured prominently in various educational projects in the early years of the Rand. Not only was he the founder of St Mary’s College for Girls; he was also involved in creating St Michael’s College and St Margaret’s School for Girls. These three schools were set up principally for children from the wealthier sector of the British expatriate community in Johannesburg. But Darragh also displayed his concern for the well-being of children at the opposite end of the social spectrum, for whose benefit he founded St Cyprian’s School, Perseverance School, St Alban’s School and St Saviour’s School (all of which served impoverished communities of all races).

A paradox characterises the role of John Darragh in the establishment of St John’s College. It is likely that, as rector of St Mary’s Church and one of the pioneers of education in Johannesburg, he provided the initial impetus for the establishment of an Anglican boys’ school. Indeed, in the very first sentence of Venture of Faith, Lawson confers on Darragh the status of founder of St John’s. Yet, as Lawson concedes, Darragh’s name is conspicuously absent from early records pertaining to the founding of the school. Rather than place himself on the proscenium, Darragh preferred to direct proceedings unobtrusively from the wings, and to allow a cast of dramatis personae to be the visible protagonists. Or, to abandon this thespian metaphor for the military one adopted by Lawson, Darragh was the general who delegated to his lieutenants responsibility for leading the opening battles of his campaign for the creation of a parish boys’ school.

It was an unidentified member of the St Mary’s parochial council who, in September 1897, raised with the council ‘the desirability of starting a Church school in the parish, on the ground that, apart from the institution run by the Marist Brothers, there was no such school for boys in Johannesburg.’ The council admitted that it would be desirable to set up an Anglican school for boys but adopted the stance that, in the prevailing economic climate, such a venture was likely to be afflicted by debilitating financial infirmity. Accordingly, the council declined to approve the creation of a parish school for boys.

Confronted by this setback, Darragh did not raise the white flag. He also did not himself now descend into the arena or engage in battle. Rather, the next tactical move in the campaign was made by Darragh’s precentor, the Revd Joseph Lowther Hodgson. Prior to coming to South Africa in 1893, Hodgson had been chaplain and senior master at King’s College, Taunton; he had also been on the staff of Hillside and Hazelwood, both preparatory schools for prominent English public schools such as Harrow, Wellington and Uppingham. His initial position in South Africa had been as headmaster of the Cathedral Grammar School at Grahamstown, which served as choir school to the Cathedral of St Michael & St George (of which Hodgson had also been precentor).

In fact, Hodgson executed two tactical moves in January 1898; if the military metaphor may be extended, he performed something resembling a pincer movement. On the one hand, he presented the parochial council with an ultimatum: he claimed that he had been brought from Grahamstown in 1897 to become precentor of St Mary’s Church on the express understanding that a choir school for St Mary’s would be started soon. However, this had not happened and, he said, if this omission were not rectified by Easter, he would resign as precentor. The parochial council – apparently desirous of retaining his services – promptly mandated a subcommittee to consider the matter of the choir school and to report back to the council a month later.

On the other hand, Hodgson launched an audacious public campaign, presumably intended to ensure that the subcommittee would apply their collective mind to the matter with due intent and expedition: his homily presented in St Mary’s Church on the morning of Sunday 30 January 1898 dealt with the topic of ‘Education’. He said that many church people considered it a ‘great deficiency in our organisation, if not a crying shame upon us as a community, that no Church of England day school is in existence [in Johannesburg]. The Roman Catholics have their great institution … we for a long period have had nothing of the sort. Now, however, by God’s help, we are changing all that; and as soon as the building can be put up, probably after Easter, we expect to open a Church of England school.’

He proceeded to explain that the school’s constitution would include a ‘conscience clause’ which would enable boys of other denominations to be enrolled, but that ‘our own boys shall be provided with a sound secular and religious education on definite Church of England principles.’ He concluded by appealing to the congregation (and, no doubt, to members of the parish council sitting in the pews below): ‘It is for you, then, my brethren, to give this movement your whole-hearted support.’ The sermon was considered sufficiently important, or controversial, to be reported (under the heading ‘St Mary’s Boys’ School’) in two local daily newspapers. Perhaps Hodgson had intended precisely that: to use the press and public opinion to exert pressure on the parochial council to approve the founding of the boys’ choir school that was so close to his heart.

The announcement of the proposed establishment of an Anglican school for boys did not generate universal enthusiasm. The Standard & Diggers’ News (one of Johannesburg’s premier dailies) expressed reservations about the wisdom of establishing a professedly denominational school: ‘The effect on the scholars can hardly be other than narrowing and prejudicial. They will learn to place a disproportionate value upon religious dogma and to fall into cliques and parties in public life.’ Possibly Hodgson had not envisaged that his project would encounter such scepticism.

However, when the subcommittee submitted its report to the parochial council in February 1898, Hodgson’s tactics seemed vindicated: the subcommittee recommended that a church school be established – subject to the caveat that the necessary funding be secured. The council accepted this recommendation on the proviso that the council itself would not assume financial liability in excess of £300 per annum. The council set up an executive committee mandated to explore further the feasibility of starting the proposed school. This committee comprised a number of parishioners who appreciated the pressing need for an Anglican boys’ school. Among these visionary men were Joseph Waldie Peirson (1865-1924), a barrister of the Inner Temple, advocate of the Transvaal Supreme Court and chancellor of the Pretoria Diocese, and William Rockey. However, the committee’s overtures to the non-governmental Witwatersrand Council of Education for funding were rebuffed, which meant that alternative sources of financing had to be found. This placed the committee in a predicament which jeopardised their project, for bears were stalking the local economy in 1898.

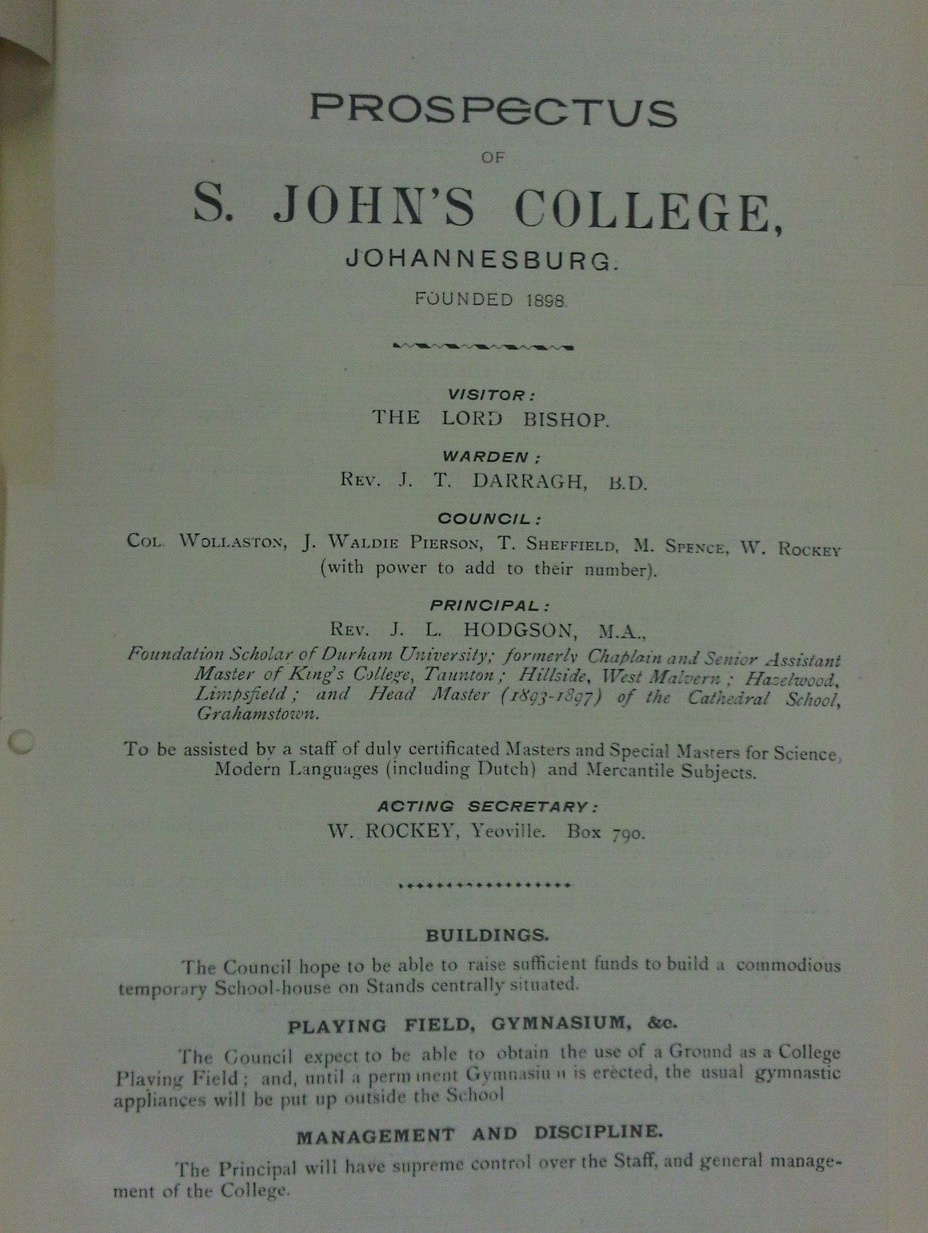

Nothing daunted, the committee proceeded to issue a prospectus for the new school early in March 1898. It is in this document that the name ‘St John’s College’ first appeared (although, as will be seen, this was a very tentative choice of name). The prospectus stated that the College council would consist of Colonel Wooliston and Messrs Rockey, Waldie Peirson, Thomas Sheffield and M. H. Spence. It was hoped that sufficient funds would be raised to be able to build a ‘commodious temporary schoolhouse on stands centrally situated’. The curriculum would include Divinity, Latin, French, Dutch, English, geography, history, mathematics and mercantile subjects.

The committee resorted to a number of fund-raising activities in an endeavour to accumulate sufficient resources to persuade the parochial council to permit the opening of the new school. Towards the end of June 1898 it was announced that an ‘immense Japanese Fancy Fair’ would be held on 7, 8 and 9 July, the aim being to ‘raise funds for the starting of a new boys’ school in connection with St Mary’s Church’. The opinion was expressed that, if the fair was successful, the school would be opened towards the end of July, with the Revd Mr Hodgson as headmaster. The fair was to entail various attractions: stalls, sideshows, substantial lunches and recherché suppers, while choruses from the operettas ‘The Mikado’ and ‘The Geisha’ would be sung.

The Japanese Fair started on Thursday 7 July 1898 in a ‘handsome’ new shopping complex at the corner of Eloff and President Streets. Mrs Catherine Eckstein (wife of the Corner House mining magnate Friedrich Eckstein) was guest of honour at the opening ceremony. Upon her arrival, she proceeded to the large hall on the upper floor, where she was received by the Revd Mr Hodgson (‘chairman of committees’), the Revd Mr Darragh (who finally emerged from the wings onto centre stage) and ‘a host of loveliness in Japanese attire’. The fair boasted nine stalls, concerts, an art gallery and dancing, with ‘lancers, waltzes and pas de quatres following one another without intermission’. The Standard & Diggers’ News reported that everything had been arranged by ‘the promoters of a fund for the establishment of a boys’ collegiate school in connection with St Mary’s to be conducted on similar lines to those of English Grammar Schools’.

After the second day of the Japanese Fair, The Star reported, under the heading ‘St Mary’s Boys’ School’, that there were reassuring signs that sufficient funds might be secured to make possible the construction of substantial school buildings:

‘The success which has so far attended the efforts of the St Mary’s Council to raise funds for the erection and establishment of a much-needed boys’ school encourages the hope that church people will make further exertions with the object ... of erecting permanent, instead of temporary, buildings for the school ... . The Japanese Fair gives promise of exceeding the most sanguine expectations that were raised when it was first mooted, and there ought to be no difficulty whatever in following it up with a series of entertainments and money-raising devices that would place the school committee in a position to launch upon a building scheme much more pretentious than was at first contemplated. ... [The] gratifying result of the present effort should convince the church authorities that the public will readily respond to any good work they put their hands to. We are informed that one of our leading architects has offered his services free for the preparation and drawing of the plans for the proposed school, if a permanent and not a temporary building is decided upon, and it is very earnestly to be hoped that the School Committee will determine upon this course. There was never a time in Johannesburg when buildings could be put up so cheaply as now, and it would be much regretted if a building of wood and iron were put up when bricks and mortar, labour and material generally are so low in price.’

This report provoked a retort in the form of a letter published, also under the heading ‘St Mary’s Boys’ School’, in the Johannesburg Times two days later:

‘The article which appeared in Saturday’s Star under the above heading was so evidently written under a misapprehension that I think it only common justice to place some of the real facts before your readers. The article in question speaks of the “efforts of the St Mary’s council to raise funds for the Boys’ School, etc.” May I point out that the fair was the outcome of the failure on the part of the lay council to raise funds for the school, and that the council had absolutely nothing to do with the fair; that on the three committees who arranged the fair there was only one councillor, and that only two, or at most three, of the council honoured the fair with their presence.

That the fair should have proved such an unqualified success was only to be expected with such an energetic ladies’ committee and the many willing helpers who wished to see the opening of the school assured, and at the same time to testify their respect for the Rev J. L. Hodgson. When, however, the Star attributes to St Mary’s council the successful outcome of the Japanese Fancy Fair, it not alone gives credit where it is not due, but also seeks to divert the credit which is due to those hard-working and enthusiastic ladies and gentlemen who devoted so much time and money to make the fair the success it was.’

Thus, there seems to have been a degree of resentment on the part of some parishioners that the parochial council had not actively thrown its weight behind the fund-raising campaign: the clear implication was that the council lacked ardour for the school project. It is also evident that, by mid-July 1898, no decision had yet been made to proceed with the opening of the school; clearly, it was still far from settled that the school would come into being at all. It is noteworthy, too, that the second letter quoted above singles out the Revd Mr Hodgson as deserving credit for his endeavours in support of the proposed school. Perhaps Venture of Faith (which depicts Darragh as the driving force behind the creation of St John’s College) has not quite done justice to Hodgson’s contribution to the College’s establishment. He amply deserves to stand alongside Darragh as co-founder.

There was no realistic prospect of new school buildings materialising at that stage. Those who held the parochial council’s purse strings understood this: when the council eventually gave its imprimatur for the opening of the school, it was decided that teaching would commence, on 1 August 1898, in the porch of St Mary’s Church: a ‘primitive lean-to structure, measuring only 25 by 9 feet’ on the Eloff Street front of the church. In the absence of more dignified premises, this improvised schoolroom had to suffice pro tem.

However, writing a quarter of a century later, Mr Waldie Peirson recalled that, a few days before the College’s inauguration, it was decided that the St Mary’s porch would not provide suitable premises, due to the constant distractions of people entering and leaving the church. As a result, it was rather a rush to find appropriate accommodation for the new school. Nevertheless, in the last week of July 1898 it was possible to announce that St John’s College would open on Monday, 1 August 1898, in ‘premises temporarily rented by the Council [at] No 32, Plein Street (opposite the Telephone Tower)’.

Lawson writes in Venture of Faith that ‘the first few future pupils of St John’s (mostly Church choristers)’ went to school in the St Mary’s porch ‘for a few weeks pending the securing of more suitable accommodation’. This suggests that teaching commenced, in the St Mary’s porch, before 1 August 1898. Indeed, some form of pedagogical activity for boys does seem to have been carried on by the Revd Mr Darragh under the auspices of St Mary’s Church prior to that date. It is clear that St John’s had an antecedent of sorts in the St Mary’s vestibule.

Formally, however, St John’s College was launched in a six-roomed villa owned by the mining baron Carl Hanau, situated at 32-34 Plein Street, on 1 August 1898. The villa, adjacent to the French Club and across the road from the Telephone Tower, was ‘a decently large place ... a conventional brick building, with corrugated iron roof, and a front verandah with bay windows on either side’.

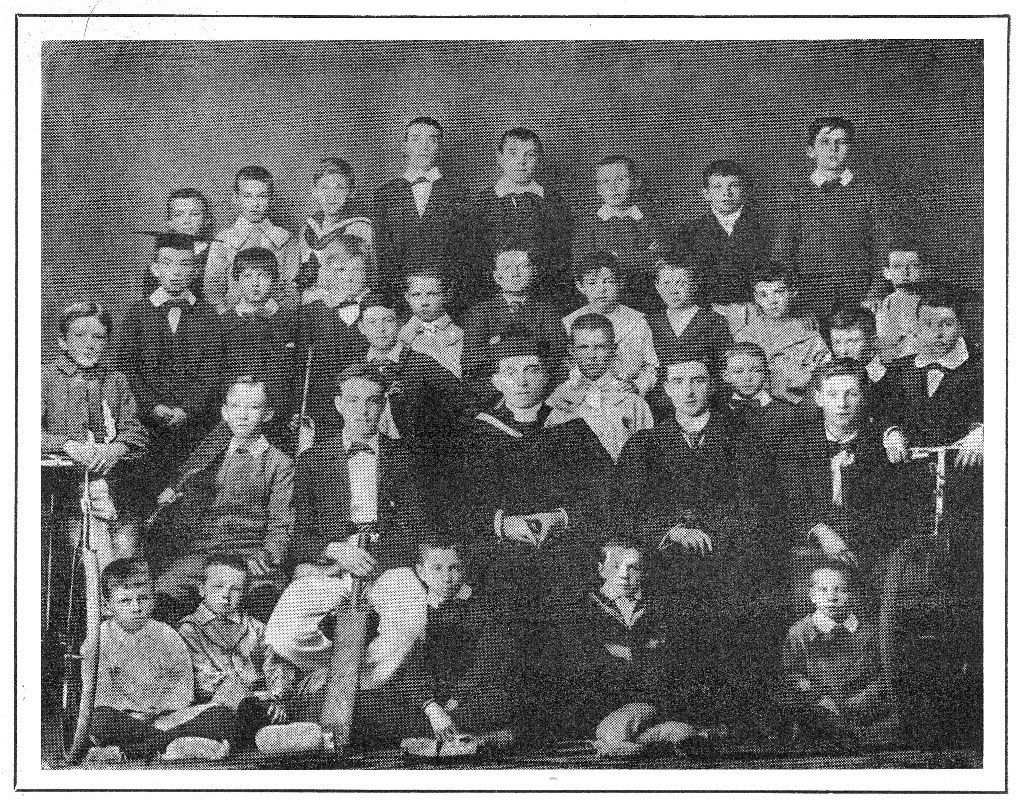

According to Venture of Faith, eleven pupils were present on the opening day. However, Leonard Durham, a boy who entered St John’s on that first day, later recalled that only six boys were enrolled on 1 August 1898. ‘The following day several boys from … the St Mary’s School for Boys run by Revd Darragh came and were enrolled.’ As the school had only two desks (presumably these were of an elongated nature that could accommodate multiple scholars, common in Victorian schools), Mr Waldie Peirson had to hurry into town to procure additional seats. The classrooms ‘consisted of benches … with inkwells. Slates were not used, all notes being taken down on paper, which was then [an] innovation to Johannesburg’. The Telephone Tower gardens served as play-ground during breaks.

Years later, Colin (‘Floppy’) Kearns, one of the boys who were enrolled at St John’s College on 1 August 1898, recalled the following about the villa in Plein Street: ‘The house had about 6 or 7 rooms. Mr Hodgson, the Headmaster, occupied two rooms and the kitchen, and the other rooms were utilised as class rooms with the exception of one small room which was the Headmaster’s study of painful memories.’ The Revd Mr Hodgson was remembered by one of the College’s early pupils, Thomas Stanton, as ‘a tall ginger-haired man of well-balanced disposition, keen on Latin and sport, … who exacted truthfulness and honour from his pupils, if not with kindly discipline, then with the cane.’

Leonard Durham’s statement quoted above, referring to ‘St Mary’s School for Boys run by Revd Darragh’, calls for comment. Darragh had been instrumental in setting up St Mary’s School for Boys, as a choir school for St Mary’s Church, in 1888. By 1897, that choir school was no longer in existence; indeed, Hodgson had been brought to Johannesburg from Grahamstown precisely to set up such a school. However, even if the choir school founded by Darragh in 1888 had become defunct, it seems that he was still running an elementary establishment known as ‘St Mary’s School for Boys’ in the infelicitous surroundings of the St Mary’s porch. With the boys who were pupils at St Mary’s School now being transferred to the newly opened St John’s College, the latter clearly did have a precursor of sorts, and so arguably can trace its ancestry back to 1888.

Not everyone was overwhelmed by fervour for the new school. A fortnight after St John’s College had opened her doors, the Standard & Diggers’ News published an anonymous letter expressing misgivings about the purpose of the school and the manner in which it would be administered: ‘Now that the school in connection with St Mary’s choir is an accomplished fact, it would be interesting to know … what steps are being taken in connection with the selection of boys to sing in the choir, and who is the arbiter in the matter of voice and musical qualification.’ The author raised the spectre that choristers (who would presumably be awarded scholarships) would be selected not on account of their vocal or musical proficiency but on the basis of the extent of their parents’ contribution to the church collecting plate.

It fell to Hodgson to set the record straight, which he did by means of a letter to the editor. He pointed out that it was inaccurate to designate St John’s College as ‘the school in connection with St Mary’s choir’, as the incognito correspondent had done. Rather, Hodgson said, the school’s raison d’être was ‘the provision of education for English boys, in the word’s widest sense: especially, but not exclusively, for members of the Church of England … on English public school lines, and under a master who shall be an English university man.’

Hodgson proceeded to explain that the bulk of the funds raised for the school had been collected at the Japanese Fair, ‘a movement largely helped by friends not in any way connected with S Mary’s.’ That being the case, said Hodgson, ‘it would hardly seem probable that the only, or even the chief motive was the establishment of a choir school for S Mary’s.’ He concluded by stating that, although choristers willing to sing in the St Mary’s choir would be admitted to the school at reduced fees, to describe the school as ‘the school in connection with S Mary’s choir is to convey an entirely false impression.’

On 16 August 1898, one of the members of the Council of St John’s College, Mr William Rockey, sent a letter to the Superintendent of Education of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, Dr N. Mansvelt. The letter, written in Dutch, was in the following terms:

‘We have the honour of hereby notifying you courteously that we have opened “St John’s College” and take the liberty of enclosing the prospectus of the named institution. We make so bold as to draw your honourable attention to the fact that we intend to provide daily instruction in the Dutch language as an ordinary subject. You would do us a great honour by providing us with information regarding the manner in which we should proceed in order to come under your supervision, and what measures we should take to enable us to obtain Government support.’

Accordingly, it appears that the Council had included Dutch in the school’s curriculum as a mechanism for securing a government grant.

From the prospectus we learn that the Lord Bishop had been appointed Visitor to the College, while the Revd J. T. Darragh had been appointed Warden. The members of the College Council included Messrs Waldie Peirson, Rockey and Sheffield (managing director of The Star, owner of the Victoria Hotel in Plein Street and churchwarden of St Mary’s). The Principal, the Revd Mr Hodgson, was to be ‘assisted by a staff of duly certificated Masters and Special Masters for Science, Modern Languages (including Dutch) and Mercantile Subjects’. The Council hoped ‘to raise sufficient funds to build a commodious temporary School-house on Stands centrally located’, and to ‘obtain the use of a Ground as a College Playing Field’. The Principal, who would be resident in the schoolhouse, would teach and examine each form at short intervals, and make himself acquainted with every boy in the College.

The prospectus stated that there was a special cap and ribbon, which would be compulsory for boys to wear. The curriculum included Divinity (‘with conscience clause’), Latin, French, Dutch, English (reading, writing, literature, grammar and composition), Geography (general and physical), History (ancient, modern and South African), Mathematics (arithmetic, algebra, Euclid) and Mercantile Subjects (shorthand, typewriting, book-keeping and commercial correspondence). Special attention was to be paid to handwriting. Extra subjects offered were Natural Sciences, Drawing, Music (piano, organ and violin), Greek and German. School fees, including charges for tuition and gymnastics, were to be four guineas (£4 4s) or three guineas (£3 3s) per term, according to the boy’s age. There would be a number of scholarships for choirboys, subject to examination.

Although the prospectus contemplated mandatory caps and ribbons, St John’s boys initially had no regulation uniform. Most boys wore Norfolk suits, the trousers of which buckled below the knee, or ‘black stockings, navy blue knickers, the school blazer, tie and cap or white boater with hatband of the school colours [which] were chocolate and pink.’ Some boys wore Eton collars.

On 31 August 1898, Mr P. K. Bermink Jansonius sent a letter (written in Dutch) to the Superintendent of Education, in which he stated that he had been appointed to teach Dutch at St John’s. He confirmed that the school was desirous of obtaining a government subsidy, and that he would be grateful to be advised of the procedure to be followed in that regard. Mr Jansonius stated, further, that St John’s then had 25 pupils, but that a substantial number of additional pupils would soon be enrolled. He enquired about textbooks that were recommended by the Superintendent, stated that English would be the medium of instruction, and concluded by saying that the principal, the Revd Mr Hodgson, would also be writing to the Superintendent regarding these matters.

When no response was forthcoming from the Superintendent, Hodgson, clearly anxious to secure a grant-in-aid, took up his pen (as Jansonius had adumbrated). In a letter dated 8 September 1898, Hodgson wrote that Jansonius ‘tells me he has written to you about the Dutch class in my school, but so far has not heard [from you]. Please let me know as soon as possible what you can do for us and what the Government require. Also be so good as [to] send the necessary forms for filling in.’ In the meantime, the Superintendent had already decided to recognise the school for purposes of a subsidy, as appears from a letter dated 6 September 1898 addressed to Jansonius.

The school’s progress was discussed at a meeting of the St Mary’s parochial council held on 13 September 1898. Mr Waldie Peirson reported that each member of the ‘provisional committee’ had subscribed twenty guineas, while a donation of £5 had been received from an external benefactor. The Japanese Fair had raised £600, of which half remained in hand, the balance having been spent on furniture, a piano and ‘many necessary sundries’. The school was in a sound financial position and, with the Council’s monthly guarantee of £25 (presumably a reference to the guarantee of £300 per annum mentioned above), it was not expected that there should be any difficulty ‘in working the school through the present bad times’.

Cricket was a popular pastime at St John’s from the outset. One of the first pupils, Colin Kearns, recalled:

‘A day or two after the school opened, someone presented us with cricket equipment which amongst other articles were two bats, one right-hand and the other left-hand. As there were exactly eleven scholars, I got a place in the team. I was ... an asset to the side as I am ambidextrous, so I could use either bat. It made no difference, I always went out first ball.’

A picture, taken in the Michaelmas Term of 1898, of the ‘first College Group’ – a collection of about thirty boys and two bicycles – confirms that cricket was a preferred diversion among the school’s pupils: no fewer than three cricket bats are on display in the photograph. And so it comes as no surprise that cricket became the school’s major extracurricular activity in the initial years of its existence. It is doubtful, however, whether formal matches were played by St John’s in those early days. The school had no playing fields. Plein Square (opposite the school) served as playground, and football was occasionally played at the adjacent Union Grounds. It is probably here that St John’s boys came with their donated bats and balls to participate in impromptu games of cricket.

The College’s first prize-giving ceremony was held at the Masonic Hall in Plein Street on 19 December 1898. In his opening address, Mr Rockey explained that the College insisted that pupils learn Dutch for it was necessary for the two ‘races’ (British and Afrikander) to speak each other’s language in order to arrive at a friendly understanding. The Revd Mr Hodgson said that St John’s now had fifty pupils, and that he could report most favourably on the school’s discipline and tone. The Bishop of Pretoria (‘a gentleman of culture, and what is more rare, common sense’) urged the boys to ‘stick to their Dutch’, pointing out that when the ‘two principal races of this country spoke each other’s languages, a firm and abiding union would be the result.’ He said more in the ‘forcibly graceful English natural to him, but this was the key-note of an excellent utterance brimful of wise advice.’

St John’s College and its ‘energetic’ principal, Mr Hodgson, were praised in press reports on the ceremony for making Dutch ‘not the least of the school’s essentials.’ Mr Rockey was reported to have disclosed ‘the ugly fact that our rich men though with us are not of us’: ‘All the commercial and financial magnates in town had been visited and asked to give support to this institution but the men who had made millions out of the soil had refused assistance.’ The proceedings terminated to the strains of ‘God Save the Queen’.

Principal sources:

JOI Agar-Hamilton Transvaal Jubilee: A History of the Church of the Province of South Africa in the Transvaal (1968); H Chilvers Out of the Crucible (1929); J König Seven Builders of Johannesburg (1950); KC Lawson Venture of Faith: The Story of St John’s College, Johannesburg (1968); P Lee ‘Anglicans in Johannesburg: A divided church in search of integrity’ (2001) 18 Transformation 232; W Macfarlane Greater Than We Know: The History of St John’s Preparatory School (2004); LE Neame City Built on Gold (1960); CF Pascoe Two Hundred Years of the SPG: An Historical Account, 1701-1900 (1901); E Rosenthal Gold! Gold! Gold! (1970); P Randall Little England on the Veld: The British Private School System in South Africa (1982); B Sundkler & S Steed A History of the Church in Africa (2000); P Venter ‘Die groei van onderwysaangeleenthede in Johannesburg, 1886-1920’ (PhD thesis, Potchefstroom University, 1950); S Welham ‘John Thomas Darragh: Anglican Pioneer’ Heritage Portal; The Johannian; The Star; Standard & Diggers’ News; St John’s College archives; National Archives