By Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

Perhaps predictably, the first half of 1905 saw a further decline in the number of pupils at St John’s College. By force of unfortunate circumstance, the staff complement was retrenched to four: the Revd Mr Carter, Messrs Rakers and Elliott and Miss Caldecott. This state of affairs, which imperilled the school’s existence, was mainly attributable to the colonial government’s dogmatic promotion of non-denominational state schools over private church schools.

Charles Ogilvie, who had been a pupil at St John’s in that era, later reflected that the government schools – heavily subsidised and well-resourced by the colonial administration to make them more attractive – ‘all but drained the very life-blood of St John’s. Many a stalwart of King Edward’s and Jeppe spent a term or two at St John’s first. So St John’s passed through a lean period and, I believe, was in some danger of extinction, until the Community of the Resurrection took the College over … And what a job they made of it!’ But that is a story for another chapter, so let us not get ahead of our own narrative.

Early in 1905, Old Johannian Johan Wilhelm (‘Billy’) Zulch, who had attended the College in the pre-Anglo-Boer War era, began to make his presence felt in Transvaal cricket. His father, J. W. Zulch senior, was well known in local cricket circles: a useful batsman, he had played for Potchefstroom in the 1880s and for Pretoria against W. W. Read’s England team in 1891/92. Now, Zulch junior was playing for Union Cricket Club in Pretoria, and his good performances for his club resulted in his selection for a combined Pretoria XI which played against a combined Johannesburg XI. Batting at number 5, Zulch (who was celebrating his nineteenth birthday) scored 51 for Pretoria.

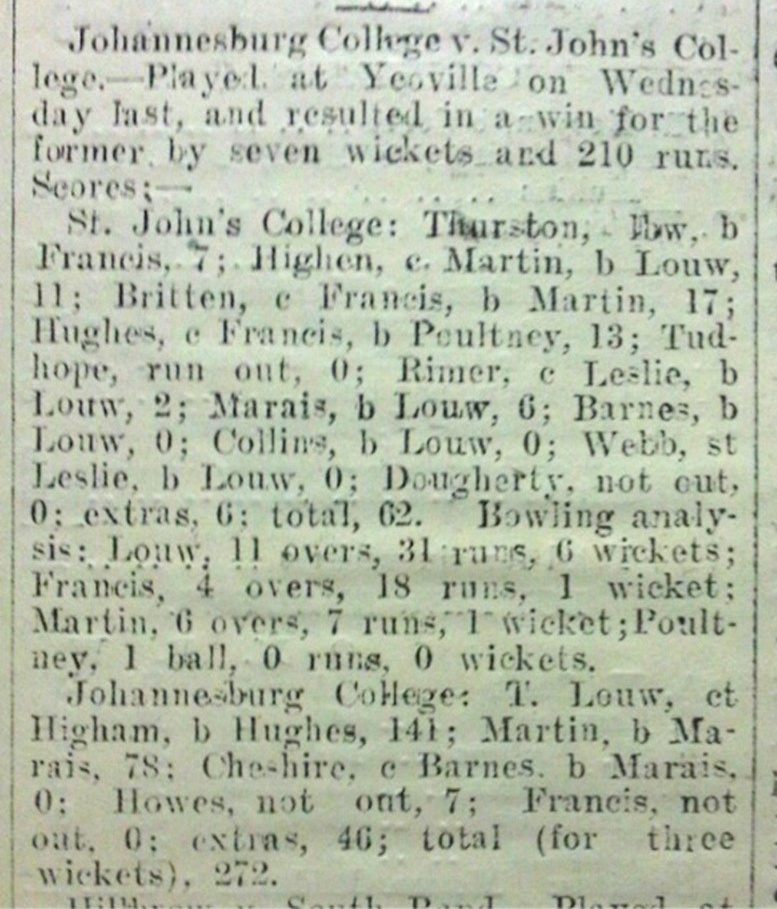

Towards the end of February 1905, St John’s played against Johannesburg College (previously known as Kerk Street Government School, and destined to become known as King Edward VII School). The match was played at Johannesburg College’s new Barnato Park premises. St John’s batted first and stumbled to a mediocre score of 62 all out. Britten (17) and Higham (11) were the only batsmen to reach double figures. The leading wicket-taker for Johannesburg College was Toby Louw (6/31), who had played for St John’s in 1903 and 1904, but whose parents had obviously now decided to enrol him at Johannesburg College. As if Louw had not done enough to torment his former teammates with the ball, he then smashed 141 with the bat, taking Johannesburg College to victory by seven wickets (and proceeding to a total of 272/3, thus also resulting in victory by 210 runs on the first innings).

Toby Louw was not the only St John’s cricketer who defected to Johannesburg College. Others included Allan Fraser and Arthur Troye (who had played for the St John’s 1st XI in 1902-‘03 and 1902-‘04 respectively) and Dick Duff (who had played for the St John’s junior team in 1903). Troye proved a valuable acquisition for Johannesburg College, taking 7/35 (including a hat-trick) against R. G. L. Austin’s XI from Pretoria in 1906. Duff played in the Johannesburg College 1st XI in 1907 and, eventually, played at first-class level for Transvaal from 1919 to 1925.

Peter Higham (who played for the St John’s 1st XI from 1903 until 1905) later recalled that, after the South African cricket team had returned from their 1904 tour of England, Mr Abe Bailey (who had financed the tour) selected a team from the Johannesburg schools to play a three-day match at the old Wanderers against the South African team. Higham himself and Henry Thurston were the two St John’s boys selected to play in that match. The remaining members of the Combined Schools XI (apart from the captain, the Transvaal and Nottinghamshire professional, Gordon Beves) were from Marist Brothers’ College and Johannesburg College. Toby Louw (‘a capital bat’) scored 57 for the schoolboys. Thurston (who also took a ‘very fine’ catch) scored 15.

Toby Louw’s parents were obviously in two minds as to where their talented son should go to school: he was back at St John’s in the last term of 1905. He wasted no time in exhibiting his batting prowess, scoring two centuries in a fortnight, the second of which was an innings of 201* against Pretoria College. This was the first (and, for the better part of a hundred years, the only) double century scored for the St John’s 1st XI. That was not the end of Toby Louw’s peregrinations, though, for his dithering parents sent him back to Johannesburg College in 1906. Incredibly, he scored another double century against Pretoria Boys’ High School in 1906. But, despite his clear aptitude for cricket, he concentrated on rugby, in which code he eventually played for Transvaal.

Be that as it may. The frivolity of playing cricket matches concealed the harsh reality that St John’s College was being confronted by the likelihood of extinction. By September 1905, the end was indeed nigh for the College. In the face of stiff competition from better-resourced state schools which seemed a better proposition than St John’s to prospective parents, maintaining the College had proved to be beyond the resources of the Diocesan purse. The school’s closure seemed both imminent and inevitable. The school was regarded as a ‘sinking ship’; it was also described as being ‘in very low water financially and otherwise.’ In the context of these maritime metaphors, one might be tempted to say that playing cricket matches in such dire circumstances amounted to rearranging the deck chairs, or one might describe it as an instance of ‘the band playing on’ – but the RMS Titanic’s fateful maiden voyage was, of course, still a few years in the future.

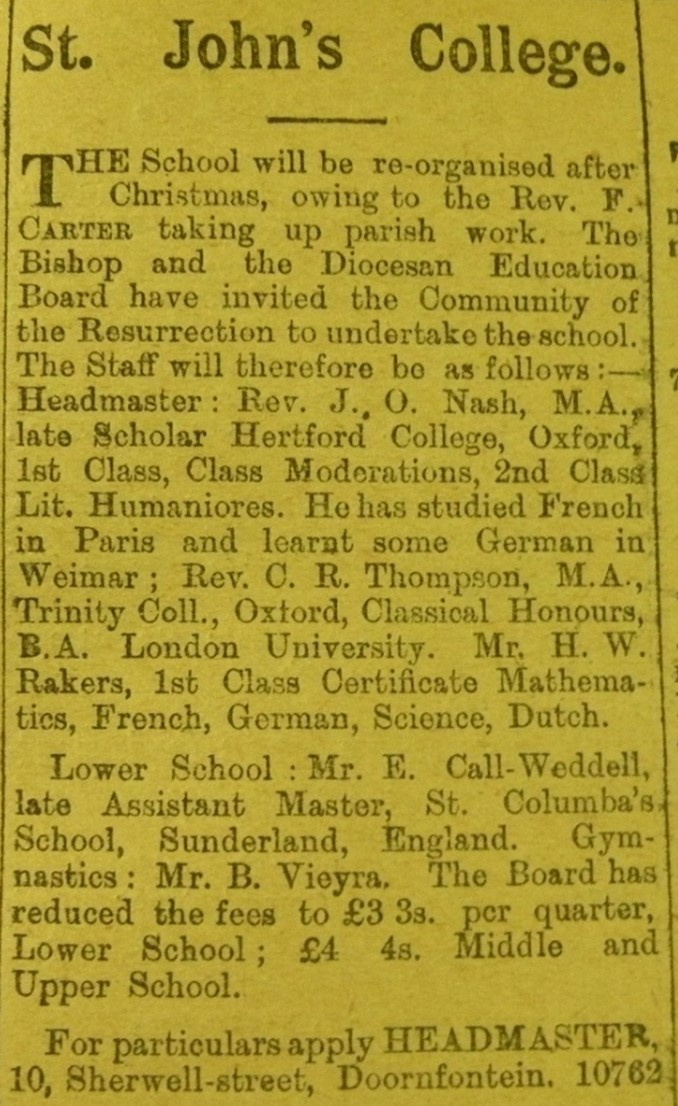

When many were ready to abandon the foundering vessel that was St John’s College, the Archdeacon of Johannesburg and Chairman of the College Council, the Venerable Michael Furse, made a decisive intervention. In September 1905, he made an appeal to the Community of the Resurrection to assume control of the College, and in that manner to keep it afloat. Fr James Okey Nash, who was attached to the Community’s small mission in Johannesburg, persuaded the Community’s motherhouse at Mirfield in Yorkshire to grant permission for the order to take charge of the College in an effort to prevent its becoming submerged. So it came about that it was announced in December 1905 that the Community of the Resurrection would be assuming control of St John’s on a provisional basis. A note published in the Diocesan Newspaper said: ‘Mr Carter is giving up S. John’s College at the end of this term, after steering the school bravely through stormy seas. He is arranging to take parochial work in the diocese and we are glad to keep him. He will be able to remember that he has scored a real good record for S. John’s. He sent in seven for the Cape Matriculation, and got seven through.’ So the Revd Mr Carter’s confidence in the prospects of his matriculation class had been quite justified.

In later years, the Revd Mr Carter seems to have been of the opinion that his role in steering St John’s through troubled waters – at a time when others, including our founder, Darragh, were resigned to scuttling the ‘sinking ship’ – had not been appreciated adequately. In a letter dated 9 November 1948 to his daughter, he wrote:

‘Many thanks for the cutting about St Johns [sic]. Yes they have missed out the effort of yours truly without which there would have been no St John’s College today. At the request of various people I have twice written the story of those days and presumably the authorities have the story in their records. Unless I and some of the staff had put a huge foot in the door at the end of ’03, the school would have been closed when Mr. Hodgson resigned. I took over then and carried on until the beginning of 1906 when the C. R. was ready to take over. It is a long story and I cannot write it again here but it was quite an exciting time for us and the present School is our justification and reward.’

On 20 December 1905, the Revd James Okey Nash of the Community of the Resurrection and Headmaster-designate of St John’s College represented the College at the annual prize-giving of Park Town School. P. T. S. was a preparatory school unrelated to Parktown Boys’ High School (which was only founded in 1920). In 1917, the headmaster of P. T. S., Mr A. R. Aspinall (who had previously been a master at St John’s College), acquired Beauvais, the mansion of Percival White Tracey in Grace Road, Mountainview, and turned it into an exclusive school. (It is the palatial white building one sees on the hillside as one travels southward along Louis Botha Avenue). R. G. L. Austin (who had played cricket for Oxford University in 1894) succeeded Aspinall as headmaster in 1919, and remained in office until 1945. The old boys of P. T. S. included several boys who later went on to St John’s College, such as Guy Nicolson and Ronnie Grieveson. P. T. S. closed in 1957.

James Okey Nash and the men of the Community of the Resurrection who were about to take over the running of St John’s College clearly were not ones to shy away from a challenge. Few people would have relished the prospect of assuming control of a school with a diminishing roll and which was in the red financially. To do so in a context where the governmental dice were heavily loaded against ecclesiastic private schools was very bold indeed – a real leap of faith.

In addition, they were inheriting a school with very little infrastructure and not much to distinguish itself by way of an identity in terms of its ethos and values. These had been articulated only at the highest level of generality: ‘a sound secular and religious education on definite Church of England principles’ (Hodgson in January 1898); ‘the provision of education … in the word’s widest sense … on English public school lines’ (Hodgson in August 1898); ‘discipline and tone’ (Hodgson at Speech Day, December 1898); the need for the races ‘to speak each other’s language in order to arrive at a friendly understanding’ (Mr Rockey on the same occasion); ‘averse to all cramming of knowledge, which engendered superficial and false knowledge … all education worth the name must be founded upon religion, and education is a process of development that brings out everything in a boy’s individual character – the good, the bad, the dullness, the brilliance – equally in all three main sides of development, namely the physical, the mental and the moral’ (Hodgson at Speech Day, December 1902); and ‘to meet the demand for a school for gentlemen’s sons on the lines of English Public Schools … meeting a demand wholly different in character’ from government schools that were perceived to be ‘devoid of tradition and associations’ (prospectus issued in 1903) .

In Carter’s two years at the helm of the ‘sinking ship’, he had displayed an admirable attitude of ‘pertinacious optimism and steady refusal to admit defeat’ in the face of great adversity. Despite the ‘steadily declining numbers, the academic and athletic standards of the School were raised, and its discipline and moral tone steadily maintained.’ ‘But for his unfailing faith there would have been no school for the Community [of the Resurrection] to take over.’ Nash later lauded Carter’s ‘brave efforts’ and acknowledged ‘his successes both in examinations and games.’ However, little progress seems to have been made during Carter’s incumbency in terms of developing an ethos and educational philosophy for the school; that is hardly surprising, as the priority at that time must have been to keep the institutional nose above inundating water. However, with the Community of the Resurrection arriving on the scene, all of this was poised to undergo a sea-change.

Principal sources:

AP Cartwright Strenue – The Story of King Edward VII School (1974); JW Horton First Seventy Years: 1895-1965 (1968); KC Lawson Venture of Faith: The Story of St John’s College, Johannesburg (1968); MW Luckin History of South African Cricket (1927); LE Neame City Built on Gold (1960); P Randall Little England on the Veld: The British Private School System in South Africa (1982); P Venter ‘Die groei van onderwysaangeleenthede in Johannesburg, 1886-1920’ (PhD thesis, Potchefstroom University, 1950); J Wentzel A View from the Ridge (1975); A Winter Till Darkness Fell (1962); H Winterbach ‘The Community of the Resurrection’s involvement in African schooling on the Witwatersrand, from 1903 to 1956’ (M Ed dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, 1994); Rand Daily Mail 3 January 1905; Transvaal Leader Weekly Edition 25 February 1905, 1 April 1905, 9 December 1905; The Star 21 December 1905, 21 September 2006; The Johannian October 1942 , October 1952, November 1953, May 1955, May 1958