by Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

Perhaps historians, endowed with the omniscience of hindsight, will say that perceptive observers when contemplating the prospects for 1914, should have seen the portents. But for ordinary mortals, the beginning of the year seemed quite run-of-the-mill, with little intimation of the fateful events that lay in store. Yet, by the end of that year, the world had changed in ways that few could have imagined, let alone predicted, rendering the quotidian experiences of January and February surreal in their mundanity. Writing towards the end of the year Fr Clement Thomson C. R. reflected that it was 'extraordinarily difficult to carry one’s mind back to anything which happened before August; things which happened in March or April seem to be veiled in the mists of quite ancient history.’

One of the routine features of Lent Term was the cricket season, dominated by fixtures against schools that would, in subsequent decades, come to be regarded as the traditional rivals of St John’s College. So, for example, on 11 and 14 February, 1914 St John’s hosted Jeppestown High School. (In those days, the school formerly known as Jeppestown Grammar School was still known as Jeppestown High School for Boys and Girls. It was to divide into separate Jeppe boys’ and girls’ schools in 1919.) St John’s won the toss and, seemingly actuated by great generosity, sent Jeppe in to bat on an easy wicket and a fast outfield. Jeppe capitalised by scoring 311 (Wytock 111). The St John’s captain, Alfred Abraham Goldstein (Hill), took four wickets, and Leslie Urquhart (Thomson) took three.

Batting on the second day on a slower outfield, St John’s struggled to mount a meaningful challenge. Still, Edward Wimble (Hill) scored 56, and Casimir Davies (Nash) 33. For a while, there was a tantalising prospect of St John’s salvaging an exciting draw. But it was not to be, the last wicket falling with only eight balls remaining before the close of play. Jeppe won by 90 runs.

The St John’s 2nd XI won their fixture against Jeppe by 25 runs, Herman van der Linde (Hill) scoring 56. The St John’s 3rd XI won by 72 runs, Leslie Patlansky (Nash) taking 4/11.

On 7 March, St John’s played another home fixture, this time against Pretoria Boys’ High School, who had won the last three encounters between the two schools. Pretoria batted first and were dismissed for 42, with Victor Langford (Hill) claiming four wickets and only one Pretoria batsman achieving double figures. If the St John’s boys thought that victory was theirs for the taking, they were soon disabused of that illusion: the first three St John’s batsmen were all dismissed without troubling the scorers, setting all hearts aflutter. St John’s gradually consolidated and eventually made 166, thanks to 37 from Wimble, 24 from Urquhart (the Senior Prefect and a batsman ‘with inexhaustible patience, hard to get out’), and a generous tally of 39 extras. St John’s won on the first innings by 124 runs.

The College’s annual swimming sports were held at the Orange Grove baths on Thursday 12 March. As in previous years, the event was organised by Mr E. W. Mole. No individual swimmer showed exceptional form, but there was plenty of good material – especially among the younger boys – that augured well for the future. David Martin won the open four lengths race; Herbert Simmons won the under 15 three lengths race; Hamish Howie continued his succession of victories at the swimming sports by winning the under 13 race; Thomas Charles won the under 11 one length race, and Guy Saunders was the winner of the Prep boys’ one-length race.

The House Relay Race was won by Mr Hill’s House, the team consisting of Victor Langford, Edward Wimble, Herbert Simmons and Herman van der Linde. The fact that several boys were likely, with proper facilities for practice, to develop into good swimmers pointed to the pressing need for the school to have its own swimming bath as soon as possible, wrote Fr Thomson. As such, when the Governor-General of the Union of South Africa, Lord Herbert Gladstone, made a gift of £100 towards fulfilment of this goal, it was received very gratefully.

On the same day as the swimming sports, 12 March, Colonel Percival Scott Beves, Commandant of the Union Cadets, accompanied by Major Jones and Captain Jardine, inspected the St John’s College Cadet Corps, which was 95-strong. He put them through their drill and signalling paces. Fr Thomson congratulated Captain Frank Carey O. C. on having won the approval of Colonel Beves.

Such were the events – nothing out of the ordinary – that occurred in Lent Term of 1914.

Since the Community of the Resurrection had taken charge of St John’s in 1906, and especially since the school’s relocation from central Johannesburg to the rustic Houghton Estate in 1907, the school had flourished. Enrolment had increased from 42 in 1906 to 240 in 1914. As a result, the school’s existing buildings had become woefully inadequate. ‘We are very much crowded,’ wrote Canon James Okey Nash, Headmaster of the College, ‘and have to use the gymnasium and dining room and boys’ common room for classes. We have 60 boarders and are obliged to hire a house to accommodate the last 20. … We have only a small chapel in the tower, in which we uncomfortably compress our boarders. School prayers have to be held in the gymnasium. We do greatly want a Chapel.’

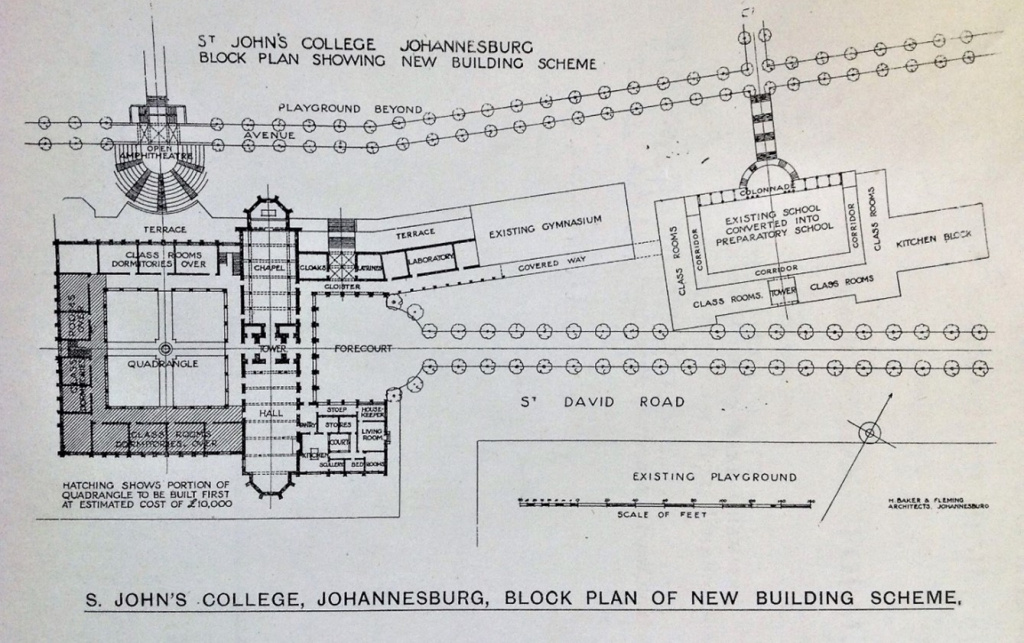

It was not only a Chapel that was required; a need had also arisen for a school hall, new classrooms, a library, common rooms and dormitories for the Upper School so that the existing buildings could house the Preparatory School. The school’s architect, Mr Herbert Baker, had drawn plans for the construction of new buildings and further development of the school grounds. It was estimated that the implementation of these plans would cost £30,000.

The estimated cost of the first phase of the planned project (erecting a block that would form the southern and western sides of a new quadrangle – what would eventually become Pelican Quad) was £10,000. The Rhodes Trustees had pledged £1,000 towards this amount, as well as a further £1,000 if the balance of £8,000 was raised by the College within a year. Donations had already been received from the Witwatersrand Council of Education (£2,000), and from the estate of the late Randlord Sir Julius Wernher (£1,000). One of the College’s Council members, the Hon. Hugh Wyndham had also donated £1,000, and his older brother, Lord Charles Leconfield, had contributed £500. With the Witwatersrand rapidly growing in prosperity, it seemed that there were many generous and philanthropic citizens who would find Baker’s noble plans appealing.

Perhaps that optimism should have been tempered by the fact that the Witwatersrand had recently experienced violent industrial action. In July 1913, a strike by white mineworkers had escalated into a general strike which, in turn, had relapsed into rioting and looting, resulting in numerous deaths and injuries. In January 1914, a strike by white railway workers developed into another general strike. This time, the government led by Generals Louis Botha and Jan Smuts proclaimed martial law, brought in soldiers to quell the uprising, prohibited picketing, banned the sale of red flags and alcohol, and deported (possibly illegally) the ringleaders of the strike, most of whom were British by birth.

Perhaps these events should have been recognised as an ominous sign of what lay in store. But this socio-economic tumult did not deter the College Council from deciding to embark on an ambitious building project. The Council hoped to complete the project over a three-year period. It was decided that Canon Nash should go to England to continue the fund-raising campaign for the project, launched late in 1913. The campaign had been endorsed by the Governor-General, Lord Gladstone. In England it was commended by personages such as Lord Selborne, Lord Milner, Lord Methuen and General Sir Neville Lyttelton; Lady Selborne was patroness of the London Appeal Committee. A supportive account of St John’s was printed in The Times (the editor of which, Geoffrey Robinson, had previously been editor of The Star in Johannesburg and had been a member of the College Council).

In these seemingly auspicious circumstances, Fr Nash had departed from Johannesburg at the end of February 1914. He sailed from Cape Town for Southampton early in March. He probably took with him Herbert Baker’s blueprint for the future expansion of the College. That blueprint envisaged that the main entrance to the College grounds would be in the east, at Pine Street. From there the College would be approached along an avenue running westward up St David Road. The focal point at the upper end of the avenue was to be the soaring Clock Tower beyond a forecourt (where David Quad today is). There was to be no Gate House entrance arch and no Tutu Quadrangle; the view of Baker’s imposing Clock Tower, flanked by the Chapel and dining hall, would be unobstructed.

Armed with these depictions of the St John’s College of the future, and aware that the development plan had the backing of influential people in London, Nash must have been confident that his appeal for donations would receive an enthusiastic and liberal response. He was to be disappointed bitterly.

Meanwhile, the College 1st XI was enjoying a successful Lent Term. Indeed, Fr Nash described the 1st XI as ‘perhaps the strongest all-round that the School has ever had. It did not contain any cricketer, as in some past seasons, who stood out as a crack amongst his fellows; but perhaps what is more satisfactory, every member of the team was of use to his side.’

The 1st XI played fifteen matches, winning nine, drawing three and losing three. The defeats came against Jeppe in the very first match of the year, against Mr J. W. Zulch’s XI (by the not trivial margin of 220 runs), and against Wanderers Cricket Club. The latter two teams were ‘overwhelmingly strong sides, consisting of entirely First League players like [Eric] Moses [Murray], late captain of Repton, and containing some cricketers who have represented South Africa, such as Zulch, Meintjes and Dixon.’

On 14 and 18 March, King Edward VII School hosted St John’s. Play did not begin punctually on the first morning owing to a storm. When play eventually got underway, King Edward’s batted first and scored 134, Goldstein taking four wickets. St John’s surpassed the K. E. S. total for the loss of six wickets and went on to make 194, of which Goldstein (‘a hard-hitting bat and an admirable crafty left-hand bowler’) scored 57. St John’s won by 60 runs on the first innings.

Victories were also recorded over Mr Villette’s XI (by 118 runs), St Mary’s English Church Men’s Society (by 103 runs), Kildare Cricket Club (by 40 runs) and Marist Brothers’ College (by 70 runs). One of the drawn matches was against Twist Street Government School Old Boys, captained by Claude Newberry. He had played four Test matches for South Africa against England earlier that season, taking 4/72 in the second innings of the third Test at the Wanderers in March 1914. He was fated to be a casualty of the Battle of the Somme two years later. As yet, however, nobody had any inkling of what loomed.

The Bishop of Pretoria and Visitor of St John’s College, the Rt Revd Michael Furse, delivered the sermon at the Choral Eucharist in St Aidan’s Church, Yeoville, on the occasion of the Old Boys’ Gaudy on Ascension Day, 21 May. He spoke about the value of tradition, and emphasised how much the boys of a school such as St John’s are indebted to the labours and self-sacrificing generosity of those who went before: ‘Truly other men have laboured and we have entered into their labours.’

Turning to matters of a temporal nature, he said: ‘In the pages of History there are the names of great nations who, because they used their greatness and might to crush and exploit smaller and weaker nations, had been by God’s judgment thrown aside on the scrap-heap. We must then use the great opportunities and privileges we have inherited for the good of others less fortunate than ourselves.’

Afterwards, a memorial tablet dedicated to the late Mr A. W. Rakers was unveiled on the porch of the school building (the entrance arch to the present Prep building). Mr Arthur Holliday, the representative of the Old Boys’ Association on the College Council, said that no one who had had the privilege of being taught by Mr Rakers could ever forget the debt of gratitude owed to him.

The unveiling ceremony was followed by a luncheon in the Gymnasium, which was attended by a large contingent of Old Boys, members of staff, the School Prefects and the College Council. The Chairman of Council, Mr (later Mr Justice) Richard Feetham, spoke of the great work of raising funds for the new buildings and of how much the Old Boys could help their old school in that regard. The chairman of the Old Boys’ Association, Mr Gerald Clarence (1904), promised that the Old Boys would do all they could for the good of their old school.

After the luncheon, the annual Past v Present football match was played. The Old Boys’ team consisted of Frank McKowen (1904), James Bell (1903), Cecil Shenton (1909), Harry Marsh (Rakers, 1910), William Currie (1904), Percy Webster (Rakers, 1910), Lawrence McKowen (1903), Graeme Mundell (Nash, 1909), William Powell (Nash, 1910), George Ware-Austin (Nash, 1910) and Leonard Denny (Alston, 1911). The Old Boys won a keen contest by a narrow margin.

After the football match came Tea (with a capital T, according to the subsequent newsletter). The Old Boys’ Gaudy was concluded with a Concert (singing, piano, violin and recitations) in the Gymnasium.

Fr Nash was absent from the Gaudy on account of his journey to England, where he had arrived at the end of March. He was on furlough and would be visiting the motherhouse of the Community of the Resurrection in Mirfield, Yorkshire, as well as his family on the Norfolk coast, but the primary purpose of his journey was, as he put it, ‘to pay various business calls in connection with our Building Fund.’

His arrival in England coincided with the culmination of the crisis over Home Rule for Ireland. In June 1913, Unionists in Northern Ireland had established the Ulster Volunteer Force, which threatened to resist implementation of the Home Rule Act and the authority of the proposed Dublin Parliament by force of arms. In turn, Nationalists raised the Irish Volunteers and planned to help Britain enforce the Act and oppose Ulster separatism. Elements in the English governing and military classes supported the Ulster separatists and raised £1 million – a hundred times the amount needed by Nash! – to fund the Ulster rebellion.

With Ireland poised to descend into civil war, circumstances were infelicitous for Nash’s fund-raising campaign: potential donors were preoccupied with the growing crisis and were reluctant to make financial commitments to obscure schools in remote corners of the Empire. Soon, however, the Irish crisis diminished into relative insignificance and was defused temporarily (although it would contribute to the ill-fated Easter Rising of 1916).

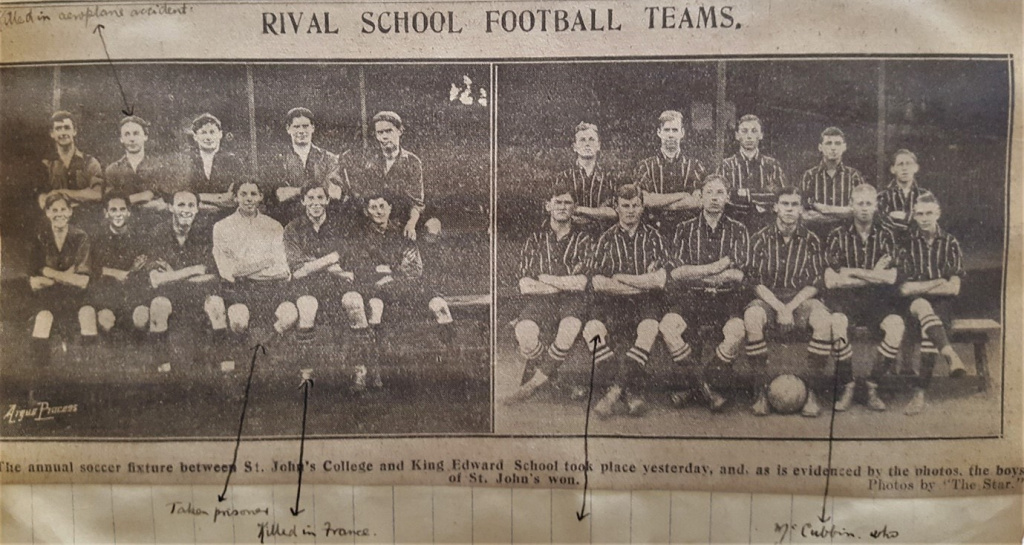

Despite the defeat to the Old Boys in the Past v Present match, the College’s first football team went on to enjoy what was probably its most successful season to date. The team ‘beat our powerful rival, King Edward’s School, for the first time, after a great struggle’, and ultimately ended second in the first league, a solitary point behind Jeppestown High School.

In the second league (under 15), St John’s recorded eighteen out of a possible twenty points. This left St John’s equal with King Edward’s on the log. After a goalless draw between the two teams, K. E. S. eventually won the play-off 1-0. In the third league (under 13), too, St John’s ended a single point behind the winning team on the log.

As had become customary, the College’s annual Shakespeare production was staged towards the end of June. This year it was decided to undertake a ‘bold experiment’ and tackle Julius Caesar. Messrs Hodges, Grundy and Wrathall took up the task of ensuring that the boys knew their lines well and intelligently. Mr Carey and a corps of boys known as ‘The Engineers’, who were assisted by the ‘Probationers’, were responsible for the lights, properties and scene-shifting.

As always, the dress rehearsal was given at the Rietfontein Lazaretto. Two performances were also held in the School Gymnasium, which was ‘packed to the doors’. The Star reported that ‘the young actors can feel satisfied in the knowledge that they were responsible for a highly creditable performance.’ Herbert Sacke took the role of Brutus, ‘and his clear enunciation gave just the right tone of sympathy.’ Jeffrey Sacke played Antony ‘and made the most of a heavy part, acting with rare restraint.’ Eric Barnett made a good Caesar, displaying ‘plenty of dignity and introducing occasionally a touch of egotism.’ Edward Wimble’s performance as Cassius ‘could not have been improved on.’

Three days after the gala performance of Julius Caesar, on 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian imperial throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. A month later, Austria declared war on Serbia, which it accused of having connived at the assassination conspiracy. When Russia mobilised to protect her ally Serbia, Germany declared war on Russia. On 3 August, Great Britain declared war on Germany. Over the following four years, the world was engulfed by the most calamitous war it had ever experienced: fifteen million people would lose their lives, and more than three million would be crippled.

These political and military developments put paid to Fr Nash’s fund-raising endeavours in England. (The times, he later said, were ‘most unpropitious’.) Nearly empty-handed, he embarked on his homeward voyage shortly after Great Britain had declared war on Germany. It would have been a scant consolation to him that he had had the opportunity of visiting some of the great public schools, such as Harrow (where the school gave their evening collection to the St John’s building fund), Winchester, Rugby, Shrewsbury and St Paul’s.

At Rugby, he had the pleasure of seeing Hubert Juta, who had been in Hill’s House at St John’s from 1910 to 1913. Juta’s grandmother was a sister of Karl Marx, author of Das Kapital and, with Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto. So Marx was Hubert’s great-uncle. Hubert’s father had immigrated to the Cape, where he had started the Juta publishing business, and his uncle was Sir Henry Juta, Judge-President of the Cape and later a judge in the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court. Hubert himself became a well-known barrister and wrote History of the Transvaal Scottish, 1902-1932.

Fr Nash’s return journey on H. M. S. Kildonan Castle occurred ‘under war conditions’. The vessel stopped nowhere en route, went far out of the usual course, and lights were screened at night. At least Fr Nash had three or four St John’s boys and their parents as fellow passengers, and the party ‘did not let ourselves be unduly perturbed.’

During the July holidays, Leslie Moses (Form V) performed a ‘gallant act of bravery … at considerable risk to himself’, as it was described by the daily Johannesburg Leader. He was on holiday with his family at Winklespruit, on the Natal south coast. A girl got into trouble while bathing at the beach, and ‘was in imminent danger of being carried away to sea and dashed against a barrier of rocks.’ When Leslie’s attention was drawn to the girl’s predicament, he ‘dashed into the water, and after swimming seventy yards, managed to reach [the girl] and rescue her from her extremely perilous position.’ Three years later, this incident had a sequel when another St John’s boy, one of the Sacke brothers, went to the rescue of a youngster who had got out of his depth in the treacherous waters at Winklespruit.

German South West Africa (today Namibia) was one of the early theatres of armed conflict in the First World War. In mid-August 1914, German colonial forces crossed the Orange River into the Union of South Africa. The British government requested General Botha’s South African government to invade German S. W. A. to immobilise wireless stations at Lüderitzbucht and Swakopmund. On 12 September, the Union Parliament voted in favour of the invasion.

This provoked a rebellion by Afrikaner nationalists, with whom singing ‘God Save the King’ still rankled in the aftermath of the Anglo-Boer South African War (1899 – 1902). Led by Christiaan de Wet, Christiaan Beyers and Manie Maritz, they viewed Botha and Smuts as traitors and saw no reason to enter the World War on the side of their recent adversaries in the Anglo-Boer War. The rebels saw the World War as an opportunity to reclaim independence for the Transvaal and Orange Free State, and so took up arms, but in some parts, the rebellion soon degenerated into a looting expedition. General Botha declared martial law. The Union Defence Forces were mobilised to suppress the uprising and to mount the invasion of the neighbouring German colony, both of which they duly did.

Fr Nash arrived back in Johannesburg early in September – in time for the annual Athletic Sports, which were held on 12 September (the very day on which, a thousand miles away in Cape Town, Parliament voted in favour of joining the war against Germany).

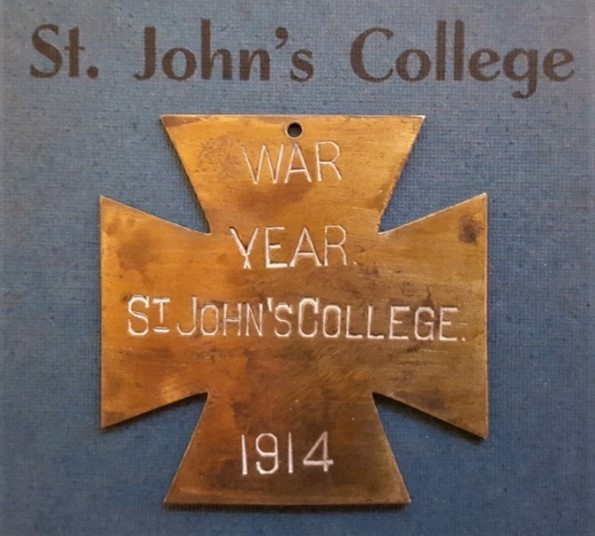

In view of the War situation, the boys had decided that, instead of the usual prizes, winners of the athletic contests should receive tokens of small intrinsic value, and that entry fees and contributions collected at the event should be devoted to War relief funds. The proceeds were divided between the Prince of Wales’s Fund and the Governor-General’s Fund. The winners’ tokens were small metal Maltese Crosses, stamped with the words ‘War Year, 1914, St John’s College’.

Fr Thomson expressed the belief that these crosses would be ‘treasured long afterwards in remembrance of the War Year.’ Perhaps the expression ‘War Year’, in the singular, indicated a belief or a hope that the War would not endure very long.

In the House Relay Race (880 yards), the Head’s House came first, the team comprising Columba Mercer, Edward Champion and Derric Fleischer. Mr Nash’s House also won the House Championship, with Mr Thomson’s House second, Mr Alston’s third and Mr Hill’s fourth. Maurice Epstein (Alston) won the victor ludorum medal, having secured the largest number of points in the Open Events.

The Inter-High Sports were held at Potchefstroom on 19 September. Fr Alston accompanied the St John’s team on the train trip to the western Transvaal (which coincided with the early days of the Boer rebellion in that region). Pretoria Boys’ High won the championship comfortably, with K. E. S. as runners-up. St John’s did not win any medals.

The volatility of the time was reflected in the staff common room. The Revd Mr Hodges, who had done good work at St John’s for three years, decided to return to England, as did Mr Mole, who had been in charge of swimming. On the other hand, while in England Fr Nash had recruited Mr Reginald Harding B. A. (Leeds) and Mr Stanley Dodson B. A. (London). Upon Fr Nash’s return, Fr Eustace Hill (a veteran chaplain of the Anglo-Boer War) obtained leave of absence from St John’s for the duration of the World War and went as chaplain to the South African forces at Lüderitzbucht in German S. W. A. One of Fr Hill’s unenviable initial duties there was to conduct the funeral service of the first three St John’s Old Boys to die on active service.

Miss Nellie Fincher, who had published The Chronicles of Peach Grove Farm, The Heir of Brendiford, Good Measure: A Novel of South African Interest and ‘Schelms’: A Natal Sketch, was leaving the Prep after a locum tenens stint. Miss Jean Stone (who had previously, before temporarily returning to Ireland, endeared herself to Prep parents and boys) was being welcomed back to the Prep.

One of the immediate consequences of the outbreak of the War was the suspension of Currie Cup and Test cricket. This meant that the cricketer Billy Zulch O. J. became available to step into the coaching breach left at St John’s by the recent retirement of Mr Alfred Atfield. Earlier in 1914, Zulch had scored 82 for South Africa against England in the third Test at the Wanderers and 60 in the fifth Test at St George’s Park. His first season in charge of the College 1st XI was quite successful. He was assisted by Mr T. E. Nash (who, with reference to his initials, was nicknamed ‘Eleven’).

On 24 October, St John’s had a home fixture against Pretoria Boys’ High. Batting first, St John’s posted 216/6, of which Eric Slade (Nash) made 63 and Edward Wimble (Hill) 35. Pretoria was dismissed for 61, with Victor Langford (Hill) taking six wickets.

St John’s hosted Jeppestown on 28 and 31 October. The opening day of the match happened to be the Feast of Saints Simon and Jude. For this occasion, the Bishop came from Pretoria to celebrate Mass in the Chapel. The Jeppe opening batsmen produced a 131-run partnership, and Jeppe ultimately made 258 (Melville 108). Goldstein took five wickets. St John’s responded with 260/8, of which David Joffe made 45, Wimble 41 and Samuel Joffe 37. The opening batsman, Robert Lillico (Hill), held the innings together by batting for 2¼ hours for his 29, St John’s winning by two wickets.

In the under 13 match against Jeppe, Albert (‘Nuggie’) Newcombe (Alston) took all ten of the opposition wickets, including a hat-trick.

The College’s annual Gymnastics Display was held on 4 November. As usual, the event was preceded by the All Saints Eucharist at St Mary’s Church, which marked the school’s ‘affiliation with that mother Church.’ Fr Nash wrote: ‘The tie between S. John’s College and S. Mary’s is a very close one, as we owe to S. Mary’s the foundation of our School.’ The Rector of St Mary’s Church, the Revd S. F. Hawkes (who had recently joined the College governing body), provided special trams for the school’s journey from Houghton to St Mary’s. The girls from St Margaret’s School also attended the service.

Afterwards, the school decamped to the Wanderers for gymnastics. ‘But alas! … the black clouds rolled up and there was quite a record storm.’ The event proceeded after the worst of the thunder and lightning had passed. Despite the inclement weather, there was a ‘very respectable gathering’, and Fr Nash thought that ‘it was the most attractive display we have ever given’: ‘Everything went with a great swing.’ He thanked the Wanderers Club for placing their gymnasium at the school’s disposal free of charge and mentioned that the gymnasium had, since the St John’s event, been converted into a convalescent hospital for wounded soldiers.

On 11 and 14 November, St John’s went up St Patrick Road for the derby cricket match against King Edward VII School. K. E. S. batted first and scored 265. Goldstein again took five wickets. St John’s reached a promising 187/4 (Urquhart 51, Slade 49 and Wimble 74), when rain intervened, with the result that the match was drawn. The match against Marist Brothers’ College was also drawn.

Mr Hill’s House came out top in the house cricket matches, with Mr Thomson’s House second.

As explained above, the response in England to Fr Nash’s fund-raising overtures had been subdued. Only about £6,500 had been generated – a substantial deficit on the amount required for the building project. Nevertheless, Nash and the College Council, chaired by Mr Richard Feetham, decided – audaciously, considering the prevailing political and economic climate – to proceed with construction of the south and west blocks of the new Upper School development. ‘Wise men would doubtless have counselled the shelving of the scheme until times were more propitious,’ writes K. C. Lawson in Venture of Faith. ‘But Nash, Feetham and their colleagues on the Council were not only men of wisdom; they were possessed also of an optimism and a faith that demanded that they should go on … foolhardy though it appeared to many.’

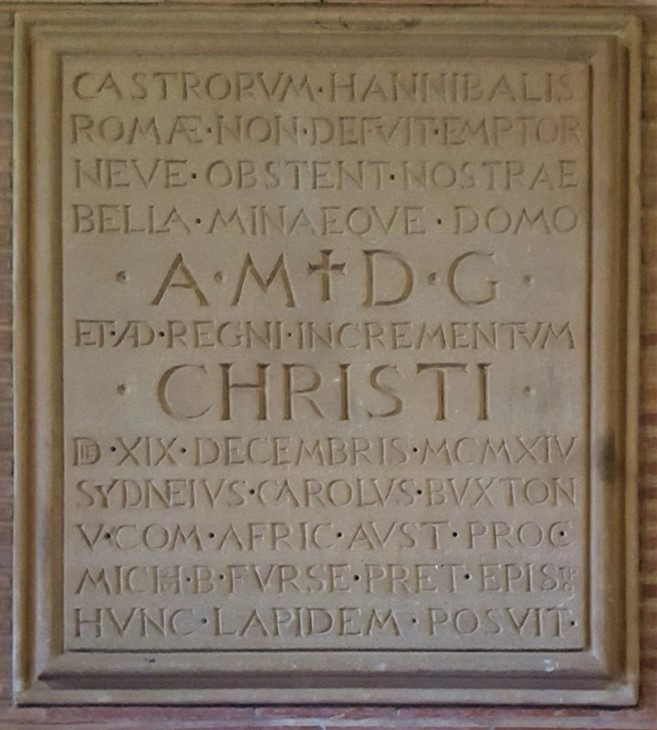

The foundation stone of the new extension was laid by the new Governor-General of the Union of South Africa, Viscount Buxton, on Prize Day, 19 December. Fr Nash left an interesting account of the occasion:

‘It was a lovely day, and crowds began to arrive; in fact, the Gymnasium could not contain them for the prize-giving, and numbers had to stay outside. The first act was the laying of the Foundation Stone of the new building at 3 o’clock. Lord Buxton on his arrival was received by a guard of honour of our Scouts and was conducted to the site by members of the Council. Our Parish Church, S. Aidan’s, Yeoville, S. Mary’s, and S. Mary the Less, Jeppe, had sent up choirs, and headed by these the whole school marched in procession to the place of the new building singing the hymn, “Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones,” with verses in honour of our patron saint. The Bishop, who had rushed up from a big wedding, conducted the service, and Lord Buxton laid the stone with its inscription of courage and hope.’

The inscription on the foundation stone, Fr Nash explained, had been the idea of Mr Feetham, who was adamant that the building project should proceed –

‘amid rebellion and war, with traitors threatening our capital, in that same calm confidence that made Rome victorious. For when the triumphant Hannibal marched to the gates of Rome, the city of Rome in defiance put up to auction the land on which the Carthaginian camp was pitched, and moreover found Roman citizens courageous enough to bid and buy it.’

It had been decided to conduct a competition for the formulation of a suitable Latin couplet. Mr (later Sir) Patrick Duncan M. P. (Colonial Secretary of the Transvaal, 1903 – 1907, and Governor-General of South Africa, 1937 – 1943) emerged victorious in the competition, having composed the following lines: ‘Castrorum Hannibalis Romae non-defuit emptor: Neve obstent nostrae bella minaeque domo.’

Translated literally, this means ‘A buyer of Hannibal’s camp at Rome was not lacking, and may wars and threats not impede our house.’ Mr Feetham’s ‘poetic art’ rendered the couplet more liberally thus: ‘The fields where Rome’s invader lay / a Roman still would buy / War’s menace let like faith today / and rising walls defy.’

After the Bishop had blessed the foundation stone, the great company was entertained at tea in the Court-Yard (‘Many mothers, generous as our mothers have ever been, had sent abundant contributions’). After this, the gathering adjourned to the Gymnasium for the concert and prize-giving.

The concert, under the direction of the organist of St Mary’s Church, Mr W. Deane, was short but ‘of course was warlike and patriotic’. To give choral expression to the Triple Entente, the Form I, II and III boys sang Theo Bonheur’s ‘Boys of the Ocean Blue’, the Russian National Anthem and La Marseillaise. Little Joseph Kirkland’s recitation brought the house down: ‘This small man from the preparatory with an astonishingly strong voice declaimed in praise of Kitchener and Jellicoe and French.’ The concert was concluded by the Form II and III boys’ rendition of Charles Harford Lloyd’s ‘Our Sailor King’.

The Governor-General, Lord Buxton, was the guest of honour at the prize-giving. The Bishop, in his speech, said that it seemed to him that every boy received a prize. Fr Nash demurred: as a matter of fact, he said, exactly 200 boys did not get prizes. In any event, he believed that, if one is going to have prizes at all, one should have a good many: ‘Every year a good number of boys well deserve prizes who do not get any. … Recognition of good work goes on all the world over, and in heaven too, we are told, and I see no reason, in spite of Mrs Montessori, why it should not be so at school.’

Lord Buxton said that a school like St John’s appealed to him, ‘as it did to those who had had a public school education, for St John’s desired to carry on the best spirit of the great schools in England.’ He spoke about the War, saying that however long the Germans were prepared to go on, ‘we are prepared to go on a little longer.’ He added: ‘No one wants to go to war, no Englishman and I am sure no Dutchman, if it can be avoided. But if you are attacked you have to defend yourself … If one part of the Empire is asked to do a certain share of the work I am sure it will not shrink from its duty, and the Union of South Africa is the last of His Majesty’s dominions to shirk carrying out a difficult task.’

Lord Buxton said that the value of a school like St John’s was that it gave ‘a wider interest to life’ and that it served ‘to make boys good-tempered and courageous and considerate.’ He thought it right that the Distinguished Service Order decoration was being awarded for ‘such qualities as cheerfulness and keeping up good spirits in comrades under severe trials.’

When it came to the distribution of prizes, Leslie Moses (‘a keen scout, and a fair cricketer … a scholar of S. John’s’) won the Bishop’s Prize for Divinity. His brother Dudley (‘a boy of admirable character and excellent ability’) won the Form V English prize. Kenneth Moore (‘one of our veterans, a trusty Prefect and a steady worker’) received the French and Science prizes, and John Greathead was the recipient of Mrs Harry Smith’s Prize for Dutch. Dudley Fynn was awarded an ‘Extra Prize for excellent work previous to departure for German S. W.’.

The Senior Prefect, Leslie Urquhart, to whom epithets such as ‘faithfulness and honour’ and ‘courtesy and cheerfulness’ were applied, received the Good Fellowship Prize. Alfred Goldstein (who was ‘much liked for his good nature and his good manners’, and who had played goalkeeper ‘most gamely and with equanimity under the most dangerous situations’) received the Kitchin Gold Medal for Latin and Dr Pershouse’s Prize for Mathematics. He also received the award for the best bowling average (56 wickets at an average of 12.48). Eric Slade had the best batting average (451 runs at 34.69), and Edward Wimble had an aggregate of 448 runs, with a highest score of 97.

The prize list indicates the classification of forms at St John’s at that time. The Preparatory School boys ascended from Class I (roughly the equivalent of today’s Grade 1) to Class IV (the equivalent of Grade 4). Then boys migrated to the Upper School, where they graduated from Form I (more or less the equivalent of today’s Upper II), Form II (now Lower III) and Form III (now Upper III) to Remove (now the first year in College), Form IV i (the equivalent of today’s Lower IV), Form IV A (the equivalent of Upper IV), Form Lower V (still known as Lower V) and Form V (today Upper V). Thus, what was then regarded as the Prep is now the Pre-Prep; the lower forms of what used to be the Upper School now constitute the Prep School; and the remaining forms have made up the College for many decades.

The Old Boys’ dance and dinner, as well as the annual Past v Present cricket match, were cancelled ‘because so many Old Johannians were away on active service.’ (Here we see an early instance of the term ‘Old Johannian’ being used to refer to alumni of the College. Until then, the more generic term ‘Old Boys’ had generally been used.)

Indeed, already on 26 October 1914, Fr Eustace Hill C. R., chaplain to the South African expeditionary forces at Luderitzbucht in German S. W. A., had written to Fr Nash: ‘Last Post has gone some time, and so have old S. J. Boys.’ By that time, about eighty Old Boys, including boys who had still been at school earlier that year, had joined regiments like the Imperial Light Horse, the Rand Light Infantry, the Transvaal Horse Artillery, the South African Mounted Rifles and the Transvaal Scottish.

Cornelius Davies (Nash, 1911), joined the Rustenburg Commando. He was present when the rebel Major Jopie Fourie was captured on 16 December 1914. Fourie, an officer in the Active Citizen Force, without having resigned his commission and still wearing his official uniform, had led a band of rebels that treacherously inflicted a dozen casualties on government troops when he opened fire under a flag of truce. He was court-martialled and executed by firing squad.

Many of these young soldiers sent letters back to Fr Nash. For example, Hugh Theunissen (Alston, 1912), who was with the Witwatersrand Rifles, wrote: ‘Concerning that cricket match v. Pretoria, Bernard [Hugh’s younger brother, who played Cinna the poet in Julius Caesar] sent me a cutting from the Mail. So I must send congratulations to the school on their splendid win.’

Rex and Wilfred Winslow (brothers of Charlie Winslow O. J., the Olympic tennis champion) were the first two St John’s Old Boys to lose their lives in the War. They were both killed on 25 September 1914 at Grasplatz near Lüderitzbucht, S. W. A., where they were stationed with the 5th Mounted Rifles of the Imperial Light Horse. According to an eyewitness, Lieutenant Holloway, they had been out on night patrol. ‘Rex Winslow, who was just a little round a small kopje, was shot clean through the heart. His brother Wilfred ran round to him and as he stooped down to raise his brother’s head to give him water, he was shot dead – through the neck – and fell on his brother, with his arms round him. He was a brave boy and they were both of them two of the best boys I had, keen an absolutely fearless.’

He continued: ‘This afternoon they were buried. We dug two graves in the cemetery here, Stettin. The Winslows were in one grave. Wilfred is on the right, Rex on the left. … All the Brigade turned out, and the Rev Mr Hill, who is with the I.L.H., read the burial service. It was most impressive, and I felt very much affected. … We are having their graves properly fixed up, and it will have the I.L.H. verse on it: “Tell England, ye who pass this monument / That we who lie here, serving her died content.” ’

Milton Thompson (Nash, 1910) (‘famous in his time as one of our very best Shakespearean actors, and one of our best pianists’) was on service with the Rand Light Infantry in S. W. A. He contracted an illness and died on the hospital ship City of Athens on 24 November. He was buried with military honours, in a grave next to the Winslow brothers at Stettin cemetery. Fr Hill conducted the service, and pipers of the Transvaal Scottish played a lament.

On 27 December, Sir Percy FitzPatrick (the author of Jock of the Bushveld, who lived at Clonave, off Princess of Wales Terrace, to the north of Roedean School) addressed a combined audience of St John’s and K. E. S. boys on the causes of the Great War. Some 150 boys came from K. E. S. to listen to Sir Percy’s speech in the College gymnasium. He illustrated his speech with an enormous map.

In a postscript to his Letter of Advent Term, Fr Nash congratulated Alfred Goldstein, Dudley Fynn and Dudley Moses on having achieved second class passes in the Cape Matriculation. ‘Fynn’s is very good business,’ he wrote. Fynn, whom Fr Nash regarded as ‘one of our ablest … a most kindly, high-minded boy, who is looking forward to ordination’, had volunteered in the Transvaal Scottish for the campaign in German South West, where they wanted him as a good shot. Having been invalided, though, he had returned from Luderitzbucht after four months’ service and had sat the Matric.

Principal sources:

B Bunting The Rise of the South African Reich (1964); C Clark The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2012); TRH Davenport South Africa: A Modern History (1989); N Ferguson The Pity of War: Explaining World War I (1998); H Giliomee & B Mbenga New History of South Africa (2007); A Hochschild To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-1918 (2011); R Kee Ireland: A History (1980); KC Lawson Venture of Faith: The Story of St John’s College, Johannesburg (1968); W Macfarlane Greater Than We Know: The History of St John’s Preparatory School (2004); R Ross, A Kelk Mager & B Nasson (eds) The Cambridge History of South Africa, Volume 2, 1885-1994 (2012); D Stevenson 1914-1918: The History of the First World War (2004); ES Thompson Let Me Tell You: The Story of the First 73 Years of the Old Johannian Association (1976); C Townshend Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion (2005); F Welsh A History of South Africa (2000); A Wilkinson The Community of the Resurrection: A Centenary History (1992); Alban Winter Till Darkness Fell (1962)

Jeppe High School Magazine June 1914 and December 1914; King Edward VII School Magazine December 1914

St John’s College Letter of Lent & Easter Terms 1913; Letter of Trinity & Advent Terms 1913; Letter of Lent, Easter & Trinity Terms 1914; Letter of Advent Term 1914; S John’s College & the War December 1914; The Johannian April 1944; The Johannian November 1953; The Johannian November 1957; The Johannian November 1964; The Johannian November 1972