by Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

Contrary to popular belief, the “Spanish” influenza pandemic of 1918 (which caused about 50 million deaths globally) did not originate in Spain. Historians and epidemiologists are uncertain about the origins of the disease, which killed more people than perished in the First World War, which was approaching its end when the pandemic struck. Various hypotheses (e.g. military camps in France, the UK and the USA, labourers brought from China to the USA via Canada) have been advanced to explain the origins and spread of the 1918 flu. Whatever its origins, it occurred in three waves (March 1918, September-November 1918, and early in 1919) and eventually caused acute illness in about 30% of the world’s population.

A little known fact about the 1918 pandemic is that South Africa was one of the five worst-affected countries in the entire world. The disease was brought here by South African soldiers who were being repatriated from France and Belgium towards the end of the war in Europe. It seems some of these soldiers were infected while en route back to South Africa, when the naval vessels on which they were travelling docked in the harbour at Freetown, Sierra Leone. When their ships arrived in Cape Town, the sick men were placed in isolation at Woodstock military hospital as a precautionary measure. The remaining soldiers who had travelled on the ships concerned were put under quarantine in a military camp at Rosebank in Cape Town, where they were examined for signs of the flu before they could be demobilised. But three days later (too soon as it transpired) all were allowed to board trains for their homes and so they dispersed across the country, taking the infection with them. In the event, approximately 300,000 South Africans (roughly 6% of the country’s entire population at the time) died as a result of the 1918 flu. [See Howard Phillips “South Africa bungled the Spanish flu in 1918. History mustn’t repeat itself for COVID-19”, Mail & Guardian, 11 March 2020]

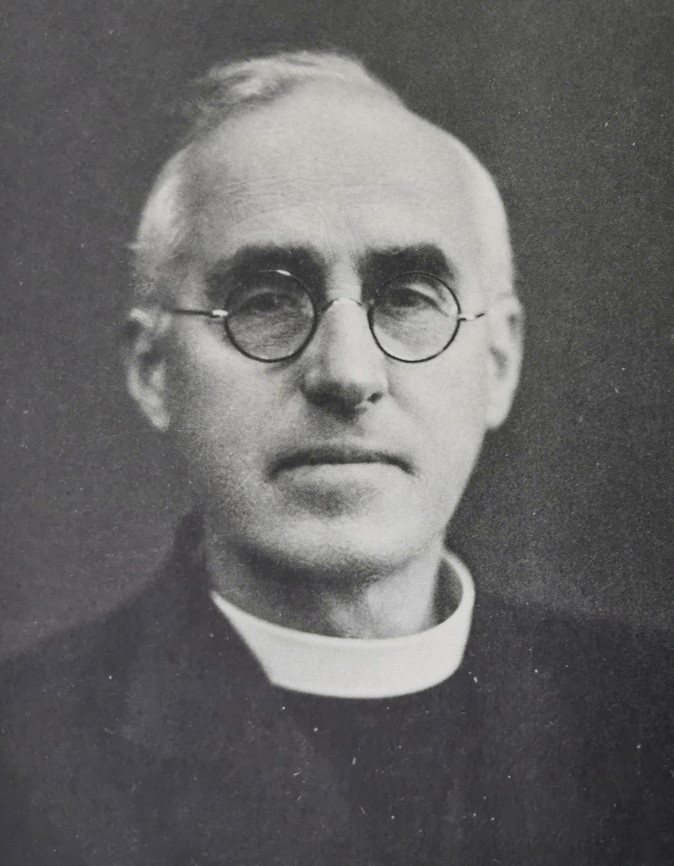

In those days, The Johannian had not yet made its appearance as the College’s annual magazine. Instead, the custom was for the Headmaster to publish a newsletter at the end of each term. These were known as “terminal letters”. During the First World War, the College Headmasters had struggled to maintain this regular practice in-between also publishing detailed newsletters about the experiences of Old Johannians and College masters in the war. Thus, instead of terminal letters Fr James Okey Nash CR had published a single Letter of 1916. After Fr Nash had become Coadjutor Bishop of Cape Town in 1917, he was succeeded as Headmaster by Fr Clement Thomson CR, who likewise published a single Letter of 1917. In October 1918, Fr Thomson published a 39-page booklet on S John’s College and the War, but the Letter of 1918 was eventually only published early in 1919.

In the introductory paragraph of the Letter of 1918, Fr Thomson explained that he had spent the better part of the July 1918 holidays compiling the booklet on the war which had appeared in October 1918. He continued: “I had meant to tackle the Terminal Letter soon afterwards. But then came the Spanish Influenza with all the correspondence and worry it involved. When at last we were permitted to start school, the whole work of the term had to be packed into a little more than five weeks. I made up my mind that no one of the events we look forward to in the last term of the year should be omitted. … In addition to all this there were the Armistice Celebrations with all the organising they entailed.” From this we learn that the “Spanish” flu caused the closure of St John’s College for a substantial part of the last term of 1918. (In those days the last term was known as Advent Term, rather than Michaelmas Term.)

Elsewhere in the Letter of 1918 we come across other snippets of information about the impact of the flu pandemic on the school. For example, in the cricket report we read that “we were able to carry on the 1st XI cricket in spite of the influenza epidemic, which closed the school in other respects for more than half the term.” The St John’s 1st XI recorded victories over Wanderers Cricket Club and KES (by 121 runs) but “failed altogether” in the match against Jeppe. Then we read the following: “But Pretoria [Boys’] High School and Marists [Marist Brothers’ College, today Sacred Hear College] were unable to raise teams against us owing to the epidemic.” Furthermore, the flu pandemic meant that the school was unable to arrange much junior cricket during that term, but Nash’s House won the inter-house shield, with Alston’s House ending second.

The report on the year’s football adds a further poignant note to the record of a year already disrupted by war and the flu pandemic. Here we read the following: “The Scarlet Fever epidemic, from which we in common with most other Schools suffered during the Easter Term, sadly interfered with Football. Quite half of the matches arranged had to be abandoned. We also had an unusually large number of accidents, in fact there was almost an epidemic of broken arms.” During the scarlet fever epidemic, a quarantine camp for St John’s boys and masters was improvised to the north of St Patrick’s Road, on the lower reaches of The Wilds.

The outbreak of scarlet fever also meant that the College was unable to stage its “annual Play as usual in June, but had to postpone it until the Trinity Term. The rehearsals had been going bravely and it seemed a thousand pities to put off the performance. But it could not be avoided.” (If history does not quite repeat itself, it certainly echoes in resounding fashion.) But despite that unavoidable delay, Shakespeare’s “Much Ado About Nothing” was eventually performed in September, when “instead of having the usual cold winter June nights, we experienced comparative warmth.”

On the final page of the Letter of 1918 the sad news is recorded that Leslie Pascoe OJ had fallen “a victim to the Spanish Influenza, which developed into pneumonia and caused his death.” We also read that, in addition to nearly sixty Old Johannians who had perished in the war, three College boys had died during the course of the year. The causes of their deaths are not specified but seem to have been unrelated to the flu pandemic.

Accordingly, although we are living through very challenging times they are not entirely unprecedented in the history of our College. We see that, 102 years ago, our College went through times probably more difficult than these confronting us now. Then, too, a pandemic necessitated the school’s closure for a prolonged period. Then, they did not have the blessing (or the curse?) of electronic communications and so were unable to continue teaching activities during the hiatus, and the entire term’s work had to be crammed into five weeks. At the end of that year, eleven boys sat the matriculation examination of the Joint Matriculation Board of the Universities of South Africa, Stellenbosch and Cape Town. Two boys achieved first-class certificates. (One of them, Walter Pollak, was only 15 years old and later became a famous QC.) But five of the eleven boys failed the matriculation exam. On the other hand, though, eleven of the twelve Lower V boys who wrote the Transvaal School Certificate examination passed, despite the year’s disruptions. - Dr Daniel Pretorius