by Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

If the end of the Anglo-Boer South African War and the reopening of St John’s College with an increased enrolment had engendered optimism about the school’s future, that sense of buoyancy proved ephemeral.

According to the Treaty of Vereeniging (which had brought the War to an end), elementary education in government schools in the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony had to be provided free of charge. Only white children derived benefit from this policy: there were no government schools for black children in these two new British colonies. Unlike in the Cape Colony, where the government made some (albeit inadequate) provision for the education of black children, in the Transvaal only mission schools offered education for black children.

The policy of free education for white children in the Transvaal was confirmed in the Education Ordinance promulgated in 1903. The manner in which this policy was implemented in the Transvaal was a matter of grave concern to denominational private schools. For one thing, most of the newly-appointed officials of the Transvaal Education Department had little experience in administering schools. One observer commented wryly that the T. E. D. ‘was like nothing on earth but a Gilbert & Sullivan opera. Those with a sense of humour held their sides with laughter.’ However, it was no laughing matter that the new colonial administration under Viscount Milner devised an education system that not only ignored black children altogether but that was antagonistic towards private church schools for white children.

Incongruously, whereas the pre-war Boer government (which had not been favourably disposed towards English-language private church schools) had paid grants to such schools, subject to strict conditions, the new British authorities deprived such schools of any form of state support. This policy proceeded from the imperative to ensure the dominance of British culture and ideology over that of the Boers; one mechanism for achieving this goal was the use of English as medium of instruction in all schools, to the exclusion of Dutch.

To facilitate implementation of this policy, education had to be under state control. Vast resources were invested in ‘undenominational’ government schools that would offer heavily subsidised tuition and superior facilities to make them more alluring than private schools. Whilst enhancement of state schools was essential in order to address the woefully deficient state of education in the Transvaal (even for white children), a by-product, if not the objective, of the Milner system was to undermine the very existence of private schools, which were perceived as unnecessary rivals to state education.

Milner’s education policy had the backing of the British government. On 17 January 1903, the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, addressed a gathering at the Wanderers Club: ‘If I were to point at this time to what … is the most urgent need of this community,’ he said, ‘I should say it was the immediate provision of a High School, efficient in every respect.’ He was talking only about schools for white children; the issue of public education for black children was not even on the agenda. As far as schools for white children were concerned, the existence of schools such as Marist Brothers’ College and St John’s College was disregarded, and the new system of public schools was implemented immediately. Premises were commandeered, and teachers were appointed at attractive salaries.

Soon there were numerous state schools for white children in Johannesburg. One of these was the Kerk Street Government High School, which had already opened in 1902. Situated in what had once been a cigar factory in the vicinity of the Tin Temple, and offering subsidised education, this new school attracted boys away from St John’s. (As will be seen, in due course this school evolved into King Edward VII School.)

The co-educational Jeppestown Grammar School was also commissioned by the T. E. D. as one of its ‘Milner schools’. Originally established by the Revd John Darragh as St Michael’s College, this school had been acquired by the Witwatersrand Council of Education in 1897. In 1903, it came under the administration of the T. E. D. and was renamed Jeppe High School for Boys and Girls. It would be divided into separate boys’ and girls’ schools in 1919.

It was in this context that St John’s College’s Lent Term commenced on 26 January 1903. However, even before the beginning of the academic year the College 1st XI had already been in action in the Transvaal Cricket Union’s second league, playing against Mayfair Cricket Club on 17 January 1903 (incidentally the very day on which Chamberlain made his ominous speech at the Wanderers Club).

At stumps on the first day, ‘matters looked decidedly cheerful for the College, in spite of the fact that only eight of their side turned up’. Presumably the absence of three members of the team was attributable to the fact that the College was still in recess. Fortunately, two of the schoolmasters made their presence felt in the College’s first innings: Mr Elliott (who opened the batting) scored 39, and the Revd Mr Carter (who came in at number 4) top-scored with 62 not out. (Elliott was ‘a powerful and fast-scoring bat’, while Carter was ‘a fine wicket-keeper’). But to Mr Candy fell the indignity of being out for a duck. St John’s scored 170, and dismissed Mayfair for 93 in their first innings (Bertram Floquet taking 6/42) before reducing Mayfair to 14/1 in their second innings.

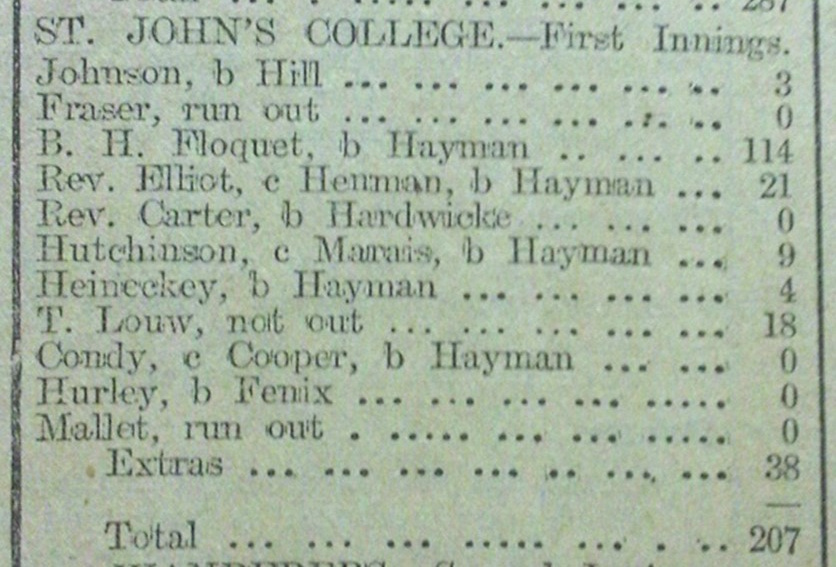

The following weekend, St John’s played against the unbeaten Wanderers Cricket Club 2nd XI at the old Wanderers ground. Although St John’s fielded a full complement of eleven players on this occasion, this match proved a more challenging assignment than the previous one. Wanderers scored 287, Bertram Floquet taking five wickets. At stumps, St John’s were in trouble at 23/2. On the second day, Floquet (who had been on 6 not out at close of play) returned to score 114 – his third century of the season. ‘During his stay he made some very fine off drives, but he had considerable luck, being let off from an easy chance in the long field and also behind the stumps.’ Mr Elliott scored 21, but the Revd Mr Carter had to trudge back to the pavilion without having scored any runs. Apart from 38 extras, Tobias Louw was the only other batsman to reach double figures, making 18 not out. He ‘made his runs in good style, and has the making of a very good bat.’ Wanderers won by 80 runs.

The St John’s College Old Boys’ Association was formed in February 1903. The Old Boys were still relatively few in number: the school had only been in existence for four and a half years, and had been closed for part of that period on account of the Anglo-Boer South African War. The Association’s principal objects were to retain contact with all who had been students at St John’s, and to run cricket and football teams. The Headmaster, the Revd Mr Hodgson, encouraged the Old Boys to practise cricket in the school nets. The average age of the members of the Association’s committee was a mere 16½ years (which is indicative of the fact that boys tended to leave school much earlier than has since become customary). The College Old Boys’ Association’s name was changed to ‘Old Johannian Association’ in 1922, by which time the appellation ‘Johannian’ had gained currency.

At a meeting of the Transvaal Cricket Union held on 27 February 1903, it was decided to introduce a Johannesburg schools competition. There were to be three leagues, based on players’ ages: the first league would have no age limit, the second league was to be an under 16 competition, and the third league was to be for under 13 boys.

In the first round of fixtures, on 4 and 7 March 1903, St John’s College II (the under 16 team) came up against Marist Brothers’ College II at the Union Ground. St John’s batted first and scored 107, of which Harford St Leger Attwell made 45. Marists scored 163 in their first innings. The St John’s second innings yielded only 58, with Attwell (23) being the only batsman to reach double figures. Marists needed only two runs in their second innings to win the match, which they did by ten wickets. Other boys in the St John’s team were Tobias Louw, Francis Fuller, Herman Danziger, Lawrence McKowen, Bernard Orpen, Charlie Read and Peter Higham.

The fixture between St John’s College III (under 13) and their counterparts from Kerk Street Government School was equally disastrous. St John’s batted first and was dismissed for a paltry 44. Only one batsman reached double figures – Eric Moses, who scored 10. The Government School scored 117. For St John’s, Harry Bernard and Cory Theys took three wickets each. In the St John’s second innings, Henry Thurston scored 21 in the total of 80. The Government School scored the required runs without losing any wickets. Other members of the College team were Edgar Warring, Cecil Hutchinson, Charles Britton, Arthur Troye, George Sturgeon, Dick Duff and Brian Dougherty.

Meanwhile, the College 1st XI was still competing in the Transvaal second league. On the second weekend of March 1903, St John’s played against Pirates Cricket Club 2nd XI at the Pirates Ground. St John’s produced a creditable performance, posting 177. Floquet scored 32 and Louw 25 not out. At close of play, Pirates had 81/3, the game being evenly poised. Ultimately, however, rain on the second day caused the match to be abandoned.

By the end of the season, Bertram Floquet (then in his final year at St John’s) headed the Transvaal second league batting and bowling averages. He had scored 618 runs at an average of 61.8, and had taken 38 wickets at an average of 10.7. These performances earned him a call-up to the Transvaal senior team for the Currie Cup match against Border on 11-13 April 1903 at St George’s Park in Port Elizabeth. Thus he became the first St John’s cricketer to play at first-class level.

At this time, St John’s was the only school in Johannesburg to play rugby. Marist Brothers College had won the Transvaal Junior Cup in 1899. However, after the Anglo-Boer War they had decided to concentrate on soccer rather than rugby. Thus, it had been a great day when, shortly after the end of the War, the number of St John’s scholars had passed the thirty mark, making it possible to take two full sides down to the Union Ground for a good tussle. This enabled the College to raise the standard of its rugby to such an extent that now, in 1903, the St John’s under 16 team won the Transvaal junior league, being victorious in the final against a team from Pretoria. ‘For this victory a magnificent cup was presented to the winning side. This beautiful and valuable prize was placed on a high shelf in the assembly hall where its sojourn was a very brief one. Someone with an open eye for the main chance came to the conclusion that it was far too expensive an article to be the plaything of mere schoolboys, so this gentleman … kindly walked away one night with the pride and joy of the pupils.’

By contrast to this great rugby success, the College’s cricketing fortunes continued to decline in Advent Term. On 21 and 28 October 1903, the 1st XI lost by 63 runs to Wanderers Cricket Club, despite the fact that the Revd Mr Carter made scores of 69 and 68 respectively in the two innings.

In mid-November, St John’s suffered another defeat at the hands of Wanderers. Wanderers scored 164, John Winslow taking 6/42, while Charles Winslow took two wickets. St John’s were bowled out for 70. The Winslow boys were the sons of Lyndhurst Winslow, an ex-Sussex cricketer who emigrated to South Africa and who was the runner-up at the inaugural South African lawn tennis championships held in 1891. Charles Winslow inherited his father’s tennis proficiency, and was destined to win three Transvaal championships. He was awarded Springbok tennis colours, and won gold medals in the singles and doubles events at the Olympic Games in Stockholm in 1912 as well as a bronze medal in the singles at the 1920 Games held in Antwerp. His son, Paul Winslow (a King Edward VII School boy), played cricket for Transvaal and South Africa in the 1950s.

Towards the end of November, St John’s played against Marist Brothers’ College at the Union Ground. Marists scored 272. Schulman (‘the finest schoolboy bat I have seen’, said Mr Elliott) made 100 before he fell to a ‘grand catch’ by Toby Louw, who took 5/14. Charles Winslow took 3/70. On the second day, Ogilvie scored 64 to keep St John’s in the game but it was to no avail as Schulman scored an undefeated century in the Marists second innings to hand them victory.

On 16 December, St John’s concluded the year’s cricket programme with a match against the Incogniti played at the Central South African Railways Recreation Ground in Braamfontein. The downward trend in the St John’s performances continued, with the Incogniti scoring 251/7 (Major Poore 109). In reply, St John’s could compile only 99 (Stanley Lambe 33, Cecil Hutchinson 18). Charles Ogilvie, who played for St John’s in this match, later recalled:

‘One of these matches [against Major Poore’s team] was on the Railway ground, Braamfontein way, which was then quite new. I remember the match because I bowled Major Poore after he had made about 150 with a ball that broke a lot and shot a lot – probably hit a stone under the mat. Major Poore congratulated me afterwards on the effort which made me take a large size in hats for a day or two.’

Thus, there had been a dramatic reversal in the fortunes of St John’s cricket: whereas the 1st XI had been very successful in the Transvaal second league in the 1902/03 season, the Advent Term of 1903 produced a string of failures. This decline was symptomatic of a general malaise in the affairs of the College – one that would, over the next few years, jeopardise the school’s continued existence.

This sad state of affairs was largely attributable to the Transvaal colonial administration’s promotion of public schools to the detriment of private schools. By the end of 1903, the Kerk Street Government School had enrolled 75 pupils, several of whom had previously been St John’s boys. In January 1904 the Kerk Street School’s name was to be changed to Johannesburg College and it moved to Barnato Park in Berea. There, the Randlord Barney Barnato had had a mansion built for himself. However, his self-inflicted death (he had leapt from the deck of a liner bound for Southampton and Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations) had left the mansion unoccupied. It was then rented for Johannesburg College by the T. E. D. at £2,000 per annum. Viscount Milner visited the new premises and expressed himself well satisfied as to the building’s suitability for a first-class secondary school.

Not everyone considered this an appropriate application of public funds: ‘If money had been chaff,’ wrote M. C. Bruce in his book The New Transvaal, ‘it could not have been spent more freely or in a more foolish manner.’ Nevertheless, the resources available to Johannesburg College enabled it to attract many more boys; during the course of 1904, it had 150 pupils. In 1911, it would become known as King Edward VII School, named after Queen Victoria’s successor.

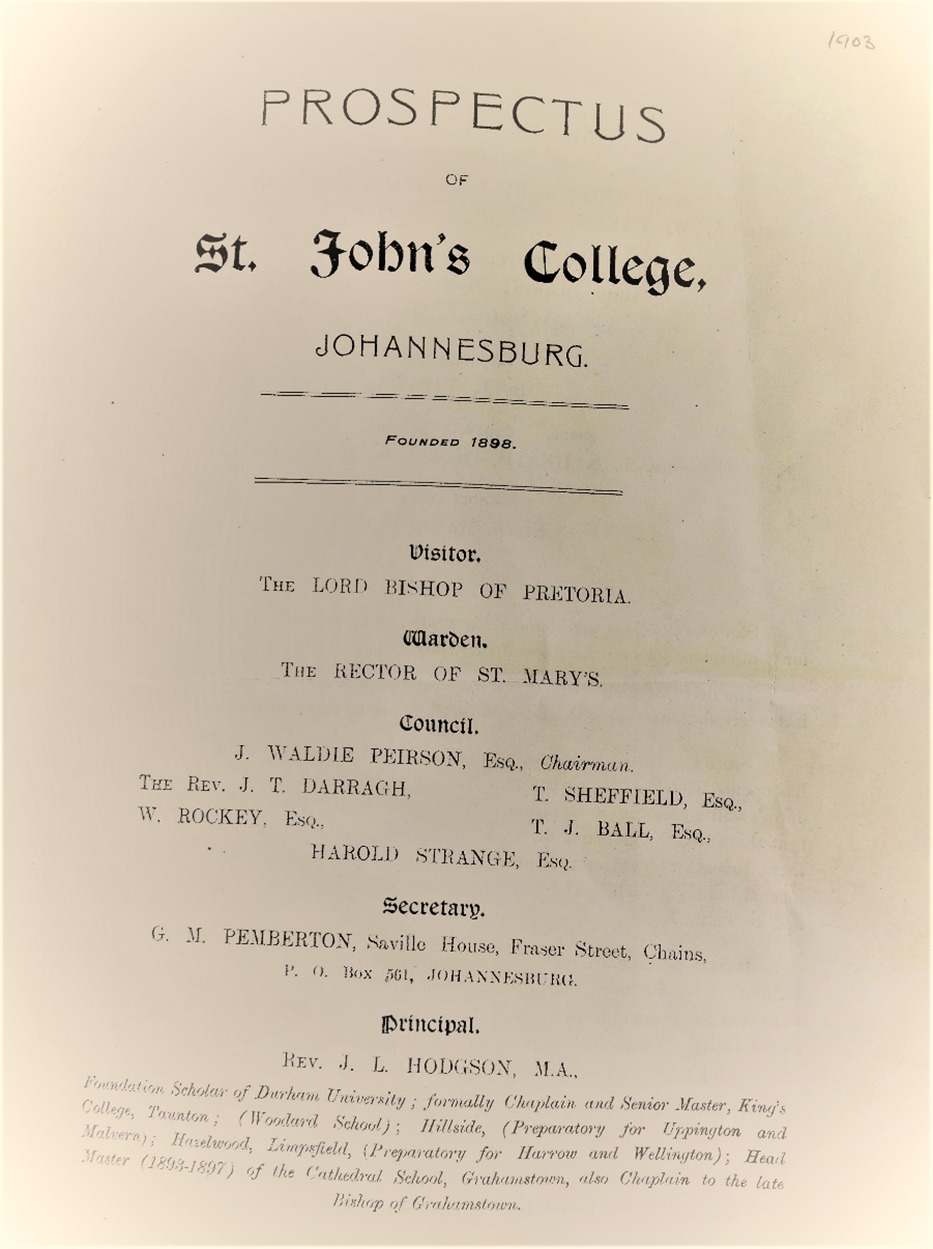

The impact of the British administration’s education policy on St John’s College was palpably deleterious – which was ironic as St John’s was to become, in time, possibly the closest South African equivalent of the archetypal English public school. In the Advent Term of 1902, St John’s had had 170 pupils; a year later, that number had dropped to 150. At least, that was the number given in a ‘gallantly mendacious’ (Lawson’s words) prospectus issued by the College Council towards the end of 1903. In reality, the College’s enrolment figures were declining steadily.

The prospectus indicated that the Headmaster, the Revd Mr Hodgson, had at his disposal a staff cohort comprising the Revd Mr Carter, the Revd Mr Robinson, Messrs Elliott and Rakers, and Mesdames Caldicott and Dunne (who were taking care of the junior boys). Mr Vieyra was in charge of gymnastics, while Mr Leo Heath provided musical instruction and Sergeant Macaulay commanded the cadet corps. The prospectus explained that St John’s had been established in 1898 ‘to meet the demand for a school for gentlemen’s sons on the lines of English Public Schools.’

The prospectus expressed the view that many parents objected to the government’s education policy and the ‘somewhat mechanical results which the methods of [government] schools produce, devoid of tradition and associations.’ It was to meet the views of parents who valued a college ‘conducted on truly English lines’ that St John’s persisted despite the odds against it – not, the prospectus emphasised, to compete with the government, ‘for that is impossible, but in the belief that [we] are meeting a demand wholly different in character.’

On this basis, it was stated (more in hope, it seems, than in conviction) that there was ‘still a demand’ for an institution such as St John’s. Tuition fees in the upper school were £8 and 8s (i.e. eight guineas) per quarter, decreasing gradually to £5 and 5s (five guineas) per quarter in the preparatory school. A reduction of £1 per quarter was given to boys who were choristers at St Mary’s Church. School hours for the upper, middle and lower schools were from 8.30 a.m. to 2 p.m.; the little boys went home at 12.30.

Principal sources:

Bruce The New Transvaal (1908); Council of Education History of Council (1916); Grant-McKenzie Forward in Faith (1998); Hawthorne & Bristow Historic Schools of South Africa (1993); Cross ‘The Foundations of a Segregated Schooling System on the Witwatersrand’ (1986); Kidson History of Transvaal Cricket (1995); Lawson Venture of Faith (1968); Le Roux ‘Historical-Educational Appraisal’ (1998); Meredith Diamonds, Gold & War (2007); Montague Bell & Lane A Guide to the Transvaal (1905); Murray Wits: The Early Years (1982); Peacock Some Famous Schools (1972); Randall Little England on the Veld (1982); Smurthwaite ‘The private education of English-speaking whites’ (1981); Thompson Let Me Tell You; Venter ‘Die groei van onderwysaangeleenthede in Johannesburg’ (1950); Wheatcroft The Randlords (1986)

Transvaal Leader 20 January 1903, 21 January 1903, 7 February 1903, 9 February 1903, 24 February 1903, 3 March 1903, 4 March 1903, 7 March 1903, 12 March 1903, 13 March 1903, 14 March 1903, 30 October 1903, 17 November 1903, 30 November 1903, 3 December 1903, 10 December 1903, 23 December 1903, 9 January 1904, 14 January 1904, 10 June 1912; Rand Daily Mail 9 April 1903; St John’s College Letter of Lent Term 1909, Letter of Lent & Easter Terms 1912; The Johannian All Saints Day 1922, Michaelmas 1923, December 1931, December 1934, May 1956, February 1978