Although the guerrilla war was still continuing in the Transvaal veld, by early 1902 a semblance of normality had returned to civilian life in Johannesburg – so much so that cricket matches were being played again. On the weekend of 11 January 1902, Johannesburg hosted a ‘miniature international fixture’ between a ‘Home-Born’ XI and the ‘Colonials’ (being those who did not have the putative distinction of an English birth and who, instead, had taken their first breaths in some remote outpost of the British Empire). The men from the Mother Country suffered an ignominious defeat, by an emphatic nine-wicket margin, at the hands of the ‘Colonials’.

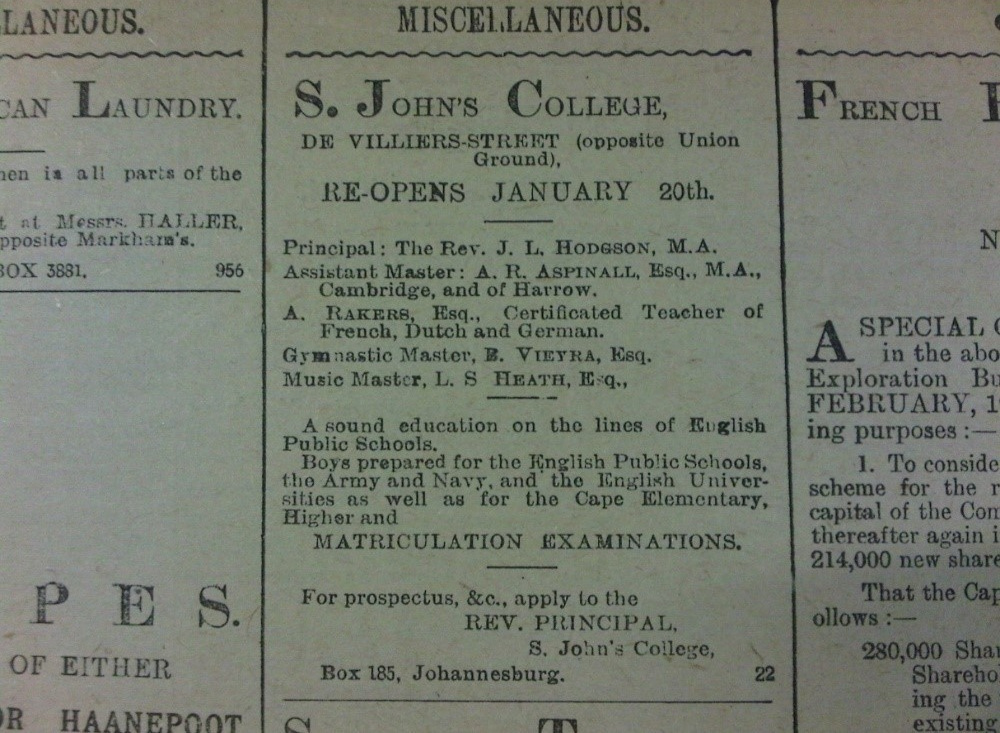

It was announced in The Star of 17 January 1902 that St John’s College would be re-opening for the new academic year on 20 January 1902. The announcement indicated that the school was no longer located in the Hanau villa in Plein Street but in De Villiers Street, opposite the Union Sports Ground.

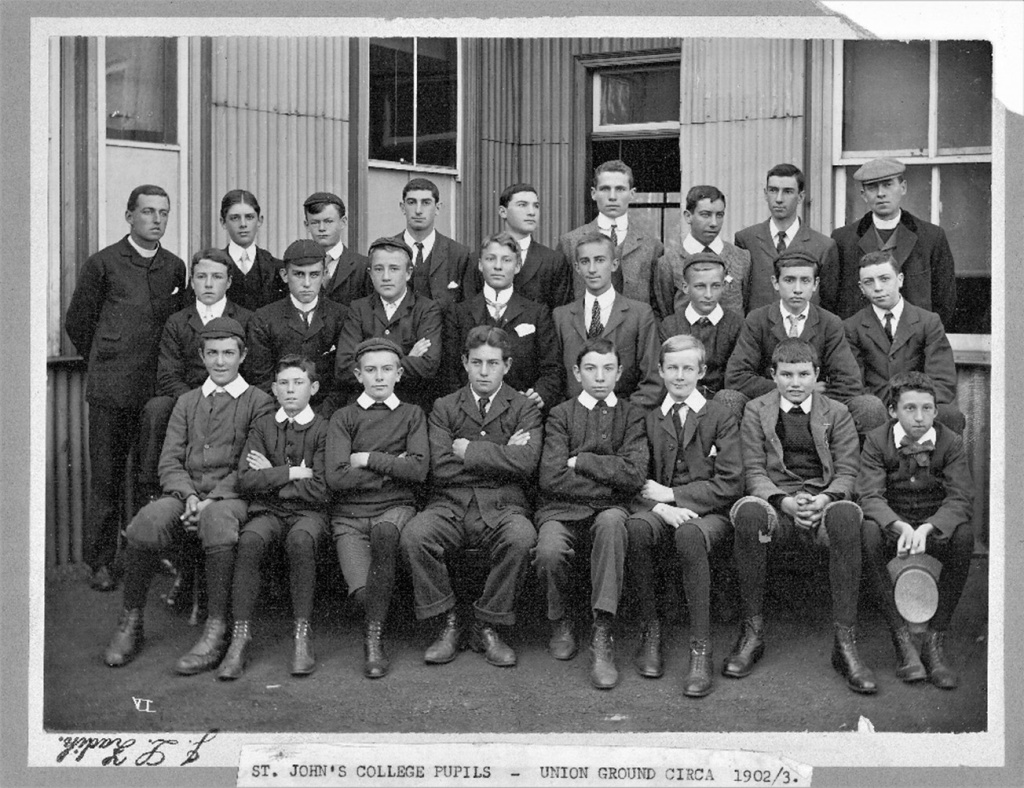

As social life increasingly displayed signs of normality despite the continuing war, many residents who had fled the Transvaal two years earlier had begun to reappear in Johannesburg with their families. As a result, there was increasing demand for places in local schools. With good schools being few and far between, applications for admission to St John’s escalated in number. Accordingly, the chairman of St Mary’s Church’s parochial council, Mr William Rockey, had taken possession of a site adjacent to the Union Ground for use by the College. A corrugated iron building (soon to become known colloquially as ‘the Tin Temple’) had been erected on this site at a cost of £600. With as many as 120 boys having been enrolled for Lent Term, even this new structure would soon become inadequate. To enable the school to enlarge the premises and acquire more furniture, an overdraft facility in the amount of £1,000 at 6% interest was obtained from the Natal Bank under a suretyship given by Messrs Rockey and Thomas Sheffield (members of the College Council).

The notice published in The Star proclaimed St John’s College’s mission as being to provide ‘a sound education on the lines of English Public Schools’; it was said that a St John’s education prepared boys ‘for the English Public Schools, the Army and Navy, and the English Universities as well as for the Cape Elementary, Higher and Matriculation Examinations.’ Historically, in England the term ‘public school’ referred to what we would call elite ‘private schools’ or ‘independent schools’. As such, the College mission statement sounded impressive; but it occupied the realm of aspiration rather than reality. In truth, the school and its facilities were of a decidedly modest standard. There was a distinct disjuncture between ambition and actuality.

Be that as it may. Circumstances had conspired such that, during the recess at the end of December 1901, St John’s College had vacated the villa in Plein Street and had moved a few blocks eastward, to the Tin Temple at the corner of De Villiers and Klein Streets (in the vicinity of the present Noord Street taxi rank). In preparation for the College’s anticipated expansion the Headmaster, the Revd Mr Hodgson, had recruited Mr Alexander Aspinall as assistant master. A Cambridge graduate, he had previously taught at the Diocesan College in Cape Town (Bishops) and, indeed, at Harrow.

Mr Aspinall was a keen cricketer; he had played for M. C. C. and for Hampshire. Accordingly, it is not surprising that, soon after his arrival, St John’s College embarked on a busy cricket schedule. Years later, Charles Steed O. J. reminisced that most of the College’s cricket matches in that period were played against military teams, comprising British soldiers deployed in the campaign to conquer the recalcitrant Boers: ‘We were particularly popular with the No. 13 Military Hospital stationed at Nourse Mines and played against their team frequently. Duncan Solomon was our star bat. More games were lost than won but we managed to have some really good tussles.’

Mr Steed’s recollections are corroborated by those of Charles Ogilvie O. J. (who attended St John’s College from 1902 until he matriculated in December 1904):

‘Among the earlier school matches which I can remember are two vs the Staff of a Field Hospital situated near the old Henry Nourse Mine on their ground. It was immediately after the Boer war and the place was packed with Military. Two [matches] vs a side captained by Major Poore – a name you will find figuring prominently in Wisdens. ... Major Luard, who had a boy at St John’s, also brought some sides against us. He, too, played for his County at Home.’

In the Lent Term of 1902, St John’s played against a Police XI (the match was drawn due to inclement weather) and against their friends at No. 13 Military Hospital (the match resulted in a comprehensive defeat for St John’s). In the match against the Welsh Regiment, Mr Aspinall opened the batting for St John’s. (As games were played against teams comprising adult men, it was customary for masters to play in school teams.) Unfortunately for Mr Aspinall, he was dismissed for a duck. The other opening batsman, Duncan Solomon, scored 21. With the aid of twenty extras, St John’s posted 86, despite the fact that the last two batsmen were marked down in the scorebook as out for nought on account of their being absent. Mr Aspinall avenged his duck by taking three wickets in the Welshmen’s innings. Young Solomon took a five-wicket haul (probably the first in the history of St John’s cricket) as the soldiers were dismissed for 57. In the result, St John’s won by 29 runs.

Easter Term commenced on 7 April 1902. Earlier that week, The Star had carried an announcement, issued by the Education Department of the Transvaal (by then under British administration), that a Government High School for Boys between the ages of twelve and sixteen years would open on 14 April 1902. The new school was to be situated in temporary buildings at the corner of Gold and Kerk Streets – only a few blocks away from the Tin Temple. (In time, this Government School was to evolve into King Edward VII School.)

The Second Anglo-Boer South African War was formally brought to an end by the Treaty of Vereeniging, concluded at midnight on Saturday 31 May 1902. In Johannesburg, the glad tidings were first announced at matins at St Mary’s Church on Sunday 1 June 1902, when, after the first reading, the Revd Mr Darragh asked the congregation to join with him in singing the Te Deum as an act of thanksgiving for the conclusion of peace.

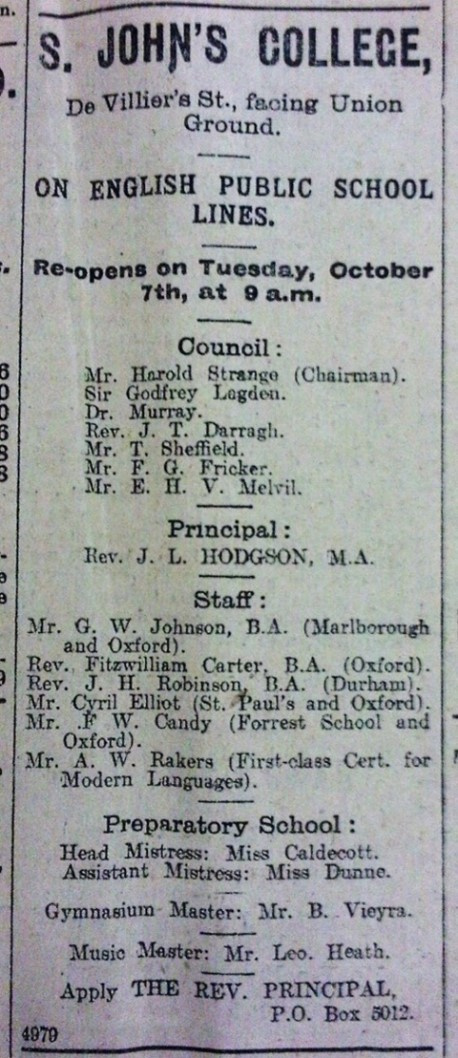

After the cessation of hostilities, many more civilians returned to Johannesburg, resulting in a further influx of boys at St John’s. It became necessary to augment the school’s teaching staff. Darragh invited the Revd Fitzwilliam Carter, who had been on the point of sailing from England for South Africa as an army chaplain when the war ended, to join the College staff. Carter had been educated at Magdalen College School and Oxford University. Lately he had been curate of Bennerton in Wiltshire.

However, in the aftermath of the war, martial law was still being enforced. Entry to the new British colonies was controlled rigorously and, before Carter could sail for South Africa, he had to apply for an ‘indulgence passage’. On 3 June 1902, the Secretary of State in London sent a telegram to the High Commissioner in Johannesburg, Lord Milner, notifying him that Carter had applied for an indulgence passage so that he could take up an appointment at a ‘Boys’ College in Johannesburg’, and enquiring whether Milner supported the application. On 13 June, Milner replied that Carter had not received a government appointment, that he was ‘probably proceeding to St John’s College, Church of England school’, and that Milner saw ‘no reason to grant indulgence passage’. Despite this initial bureaucratic resistance, though, Carter was eventually allowed to travel to Johannesburg to join the St John’s staff.

Other members of staff appointed during this period included the Revd J. H. Robinson B. A. (Durham), Mr C. T. Elliott B. A. (Oxon), Mr W. F. Candy B. Sc. (Oxon) and Mr George Wilfrid Johnson B. A. (Oxon). Miss Caldecott headed the preparatory section of the school, and she was assisted by Miss Dunne.

With nearly 180 boys now on the school roll, the ramshackle Tin Temple was bursting at the seams. Mr Elliott, who was Games Master and Bursar, recorded the following about the Tin Temple:

‘Our school edifice was of corrugated iron and wood, dismally cold in winter and a bake house in summer. In winter I used to break off the class, send the boys to run six times round the Union Ground, and then we would carry on, somewhat breathlessly, with our work. In summer, conditions were not very much less unpleasant, the boys were not wholly clean – water being somewhat scarce. If one opened the windows, volumes of dust arrived, so that we had to choose between two evils, smell or dust’. [Nevertheless, it was possible] ‘to forge a happy family, good fun and a certain inculcated smattering of knowledge.’

Another description indicates that the Tin Temple’s classrooms ‘formed three sides of a square, the centre was a large, rather dusty, red-earthed “quad”. A low-roofed bicycle shed occupied the fourth side, the corrugated-iron fence, very new and shiny, which surrounded the School grounds, forming the back of the shed.’ Elsewhere we read that the school buildings were ‘a line of corrugated-iron huts round a dusty square. There were no boarders and no facilities for games. One of the amusements of the boys was to collect locusts and let them loose in the classrooms.’

A signpost erected at the south-western end of the Tin Temple grounds, at the corner of King George Street and Plein Street, announced: ‘St John’s College Temporary Premises’. There was something inherently optimistic in that description: this corrugated-iron structure was intended to be a mere transitory home for a school destined for greater things.

A recurring theme in the College’s early days was the perennial lack of funds to acquire the necessary amenities. Yet, shortly after St John’s, with her ‘motley collection’ of about 180 boys, occupied the Tin Temple, a sum of fifteen shillings was appropriated for the purchase of a cricket bat. A wire-netting cricket net was built in the Tin Temple grounds. According to Mr Elliott, it ‘served its purpose admirably.’ However, because there was no room to get out of the way of a firmly struck straight drive, those of lesser agility were occasionally injured.

Charles Ogilvie O. J. later described these rudimentary cricket facilities as follows:

‘The netting covered the sides and top right down to the bowler’s crease. This prevented loose balls from being hit through the Headmaster’s window, but it had its drawbacks. Any bowler with a high trajectory would have the mortifying experience of seeing his ball hit the top of the net and flop down on to the pitch ten yards away. We also had small movable nets that we pitched on the Union Ground. These, by contrast, were so small that any stroke wider than a square cut or a stroke to leg would have to be fielded. So armies of fielders were co-opted for net practices’.

‘As space was limited the net [at the Tin Temple] was enclosed the entire way from bowler to batsman. Needless to say high, flighted stuff could not be bowled. The net was supported by stout timber posts and one became expert at ducking when a hard drive came back at one off one of these posts.’

Robert Walton Ball (who attended St John’s College from 1904 until 1906) remembered:

‘Within the precincts of the school there was a small area of ground where, in cricket nets, we juniors occasionally were shown how to hold a bat. The regular rival school in games was the Marist Brothers’ College, situated then nearer Doornfontein; and what a battle royal took place at cricket or football! Sometimes we were given facilities to play at the Wanderers Club, but more often than not these matches took place at the Marist Brothers’ School.’

As appears from these assorted recollections, the Tin Temple had no playing fields, with the result that St John’s had to make arrangements to play games elsewhere. Many years later, James Okey Nash (onetime Headmaster of the College and then Coadjutor Bishop of Cape Town) recalled that games of diminished importance were played on the Union Ground, with pedestrians crossing through while games were in progress; for more significant matches, St John’s had to obtain a ground from the Wanderers Club, ‘who were very good to us.’ (In those days, the Wanderers Club was located in downtown Johannesburg, in proximity to Park Station, within walking distance from the Tin Temple.)

Mr Elliott also recalled:

‘Games were our great problem. We had the Union Ground to play on but seemed to have nothing with which to play. I had brought out [when coming from England] three well-seasoned cricket bats and lent them to the boys for practice. Those bats did not last many days since the boys preferred to play with the edge of them, which made the splinters fly.’

On 1 October 1902, a cross-country race between four representatives of each of St John’s College and Marist Brothers’ College took place. Setting out from the Union Ground, the boys ran four miles alongside the Braamfontein spruit, then circled past Nazareth Home (in Yeoville) and Barnato Park (in Berea), back to the Union Ground via Hospital Hill. The athletes were accompanied by horse-mounted race officials and were pursued by a retinue of boys on bicycles. The guest of honour, the Governor of the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony, His Excellency Lord Milner, arrived at the Union Ground at 4.45pm, and was met by the Revd Mr Hodgson and Brother Valerian of Marists. The arrival of the equestrian functionaries and juvenile cyclists gave due notice of the impending completion of the race. It was a ‘capital finish’, resulting in a dead heat between Hugh Mallett and Allan (‘Tyke’) Fraser, both of St John’s, in a time of about 29 minutes. Lord Milner presented the prizes. Mr Hodgson proposed a vote of thanks to Lord Milner for his attendance, and called on the boys for three cheers for His Excellency, which were given ‘right lustily’. (Both the victors, Mallett and Fraser, were destined to lose their lives in the First World War.)

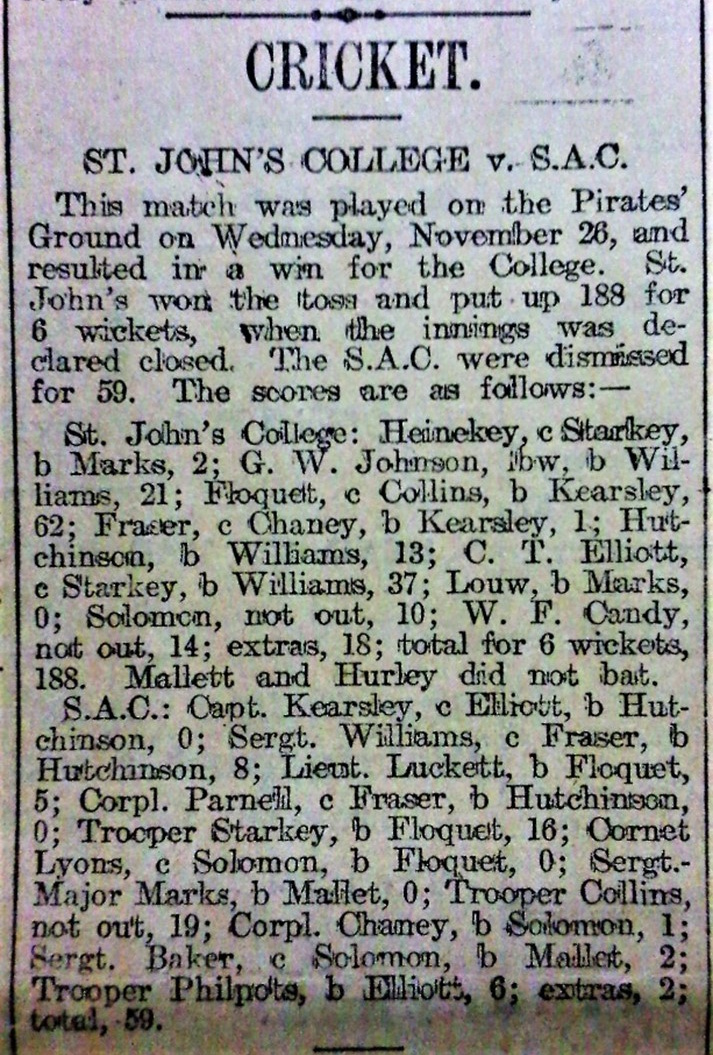

Because of the dearth of cricket-playing schools in Johannesburg in those days, St John’s College entered the Transvaal Cricket Union’ second league division. Mr Elliott later recalled:

‘With the aid of some of the masters we were able to put in so useful a side that we nearly won the league. Our great player was Granny Floquet, who finished up the season with an average of 80. … Clive Hutchinson, C Flurian, R Kearns, EJ Hurley, Jimmy Goch, G Heinekey, C Fraser, A Troye and D Solomon were others who were also in this team. What surprised me was that out of the eleven we had eight really good wicketkeepers.’

On 25 October and 1 November 1902, St John’s played against the Central South African Railways XI at the Union Ground. The Railwaymen scored 250. St John’s commenced batting in poor light, and had 28/1 when stumps were drawn. On the second day, Mr Candy went on to score 29. The Revd Mr Carter and Bertram (‘Granny’) Floquet then made a stand of 97, when the latter was dismissed, having made 62 in fine style. Mr Carter continued to play the bowling with comfort but was out leg before wicket for 66 just when St John’s felt certain of passing the opposition score. St John’s were all out for 221. In their second innings, C. S. A. R. were dismissed for 78 (Floquet and Clive Hutchinson taking four wickets each), leaving St John’s 107 to get in twenty minutes. The Revd Mr Carter and Floquet (43*) knocked off 64 of the required runs when Mr Carter was bowled and time was called.

On 10 November 1902, the College played against the Government Mines Department who won the toss, elected to bat and scored 48 before losing a wicket, but then collapsed to 119 all out. For St John’s, Floquet took 8/47. Mr Johnson (79) and Gordon Heinekey (21) put on 106 for the first wicket – probably the first century partnership ever recorded for St John’s. St John’s declared at 275/6, with Floquet on 78* and Fraser on 26*. The mining officials’ second venture yielded 98/9, St John’s thus winning by 156 runs on the first innings. The St John’s fielding was ‘keen’.

St John’s played against Mercantiles Cricket Club at the Union Ground on 12 November 1902. Having won the toss, St John’s batted first. Solomon (75) and Fraser (43) opened the batting and, within days of the feat first having been achieved, recorded another century partnership for the first wicket. Mallett scored 21* and Ogilvie 15*, St John’s declaring at 184/4. The merchants were dismissed for 76 in their first innings, Toby Louw taking seven wickets. Following on, Mercantiles were all out for 75, Louw this time taking a hat-trick. St John’s won by an innings and 33 runs.

In 1902, Mr Harold Strange succeeded Mr Joseph Waldie Peirson as Chairman of the College Council. Mr Strange was a director of Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Company, the holding company of the business empire established by the Randlord Barney Barnato (by then deceased). One of Strange’s fellow directors was Harry Stratford Caldecott (possibly the father of Miss Caldecott, who was in charge of the St John’s preparatory section). Strange was an accomplished swimmer. He was chairman of the Wanderers Club committee, and was a great bibliophile. Upon his death, his collection of books was bequeathed to the Johannesburg public library, where it remains as the Harold Strange Library of African Studies, reputed to be one of the finest collections of Africana in the world.

As appears from the notice published in The Star on 3 October 1902 (above left), Mr Strange’s colleagues on the College Council included Sir Godfrey Lagden, at that time the Commissioner of Native Affairs in the Transvaal Colony and later vice-president of the Royal Colonial Institute in London. Another member of Council was Mr Edward Harker Melvill, a well-known land surveyor and engineer, and a Fellow of the Geological Society of London and of the Royal Geographical Society. In 1903, he was appointed by the Lieutenant-Governor of the Transvaal to serve on the Technical Education Commission, which made recommendations on the future of higher education in the Transvaal. The residential area of Melville in Johannesburg is named after him.

Dr James Welldon, former headmaster of Harrow and lately Bishop of Calcutta, visited St John’s College on 15 November 1902. The St John’s boys, numbering in excess of 200, assembled in the Tin Temple’s quadrangle. The Bishop said that, owing to his experience as a schoolmaster at Dulwich College and Harrow, he had a very keen knowledge as to the character of boys, and could pick out the bad from the good one by merely looking at their faces. He exhorted the boys to be honest and truthful, to look up to their College and support it whether at study or in the playing-fields. As they conducted themselves at school, so would they later in life; but it was not always the studious pupil who came out on top after leaving school. The Bishop told the boys that they would be the future men of South Africa, and that the future task of upholding the Empire would be in their hands.

On 3 December 1902, St John’s played against Wanderers Cricket Club at the latter’s grounds. Wanderers fielded a strong team which included A. E. Ochse, C. B. Llewellyn, W. A. Shalders and V. M. Tancred, all of whom had played Test cricket for South Africa. St John’s won the toss and audaciously sent Wanderers in to bat. Fortune favoured the brave, and Wanderers were restricted to 169/7. Mr Johnson (21) and Heinekey (39) scored 67 for St John’s for the first wicket. After Floquet had added 29, Mr Candy and Mallett secured a famous victory for St John’s by one wicket.

On 6 and 13 December, St John’s played against Marist Brothers’ College Old Boys. Old Maristonians batted first and scored 237. Louw took five wickets. At close of play on the first day, St John’s had 100/1. Resuming on the second day, Mr Johnson (49) and Floquet took the score to 147 before the former was dismissed. Floquet, who ‘was in fine form, giving a great display of his ability’, remained at the crease until the score was 193, when he was bowled for 120 – the first century scored by a St John’s boy. It was ‘an excellent innings, without a single chance to hand.’ Then a rot set in and seven wickets were down for 206, but the last three men took St John’s past the Old Maristonians’ total.

Floquet scored another century in the very next match, played against the Incogniti (a ‘wandering’ cricket club i.e. one without a home ground, originally established in England in 1861) at the Union Ground on 10 and 17 December 1902, making 110 in the St John’s second innings total of 151/2.

Unlike the modern custom, according to which the academic year ends early in December, in those days school continued until shortly before Christmas. This was in imitation of the standard practice in England. As a result, the College’s annual prize-giving ceremony (which came to be known as ‘Speech Day’, also following English public schools’ terminology) usually only took place in mid-December. In 1902, Speech Day was held on Saturday, 20 December. The event was attended by some 700 people, including the Bishop of Pretoria.

Halfway through the proceedings, the electric lights went out. (Loadshedding is, it seems, not a phenomenon of recent provenance.) The ceremony continued in darkness relieved only by candles glimmering on the platform. ‘This considered, and the fact that the occasion was the Christmas “breaking up”, and that some hundreds of high spirited boys were present, the order and quiet kept, though by no means absolute, were quite of commendable moderation.’

In his address, the Revd Mr Hodgson said that the College now had 170 boys, taught by eight masters and two governesses. Turning to the College’s educational ideals, he expressed himself averse to all cramming of knowledge, which engendered superficial and false knowledge, and entailed the neglect of ‘dull and backward’ boys, and undue and unnatural pressure on the more gifted. In his opinion, all education worth the name had to be founded upon religion, and education was a process of development that brought out everything in a boy’s individual character – ‘the good, the bad, the dullness, the brilliance – equally in all three main sides of development, namely the physical, the mental and the moral.’

Principal sources:

Lawson Venture of Faith (1968); Neame City Built on Gold (1960); Mosley The Life of Raymond Raynes (1961); Venter ‘Die groei van onderwysaangeleenthede in Johannesburg, 1886-1920’; Wheatcroft The Randlords (1986); National Archives TAB CS94 5309/02; CL Ogilvie OJ ‘Old Johannian Association History’, SJC Archives I 1 (1898-1905); CT Elliott The Johannian All Saints’ Day 1922; JO Nash ‘The Early Days of the C.R. and S. John’s’ The Johannian Michaelmas 1923; C Steed OJ ‘Bygone Days’ The Johannian December 1934; CL Ogilvie ‘St John’s College 1901 to 1904: An Old Johannian’s Recollections’ The Johannian October 1952; R Walton Ball ‘The First Decade of St John’s (1898-1908)’ The Johannian May 1958; The Johannian February 1978; The Watchman September 1923; The Star 13 January 1902, 24 January 1902. 29 January 1902, 4 February 1902, 22 December 1902; Standard & Diggers News 4 February 1899, 8 March 1899; Transvaal Leader 2 October 1902, 4 October 1902, 6 October 1902, 28 October 1902, 4 November 1902, 12 November 1902, 14 November 1902, 15 November 1902, 5 December 1902, 6 December 1902, 13 December 1902, 15 December 1902, 23 December 1902; Rand Daily Mail 4 December 1902, 16 December 1902, 23 December 1902