by Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

Towards the end of 1903, the Headmaster of St John’s College, the Revd Mr Hodgson, returned to England due to health problems. At the beginning of 1904, the College Council, mindful of the school’s ‘grim’ situation (it was in debt to the considerable tune of £2,000), began to give consideration to the possibility of closing the school. However, the Revd Mr Darragh (the rector of St Mary’s parish church, under whose auspices the school had been established) was away in England on furlough. As a result, the Council decided that the school should soldier on for the time being.

The Revd Mr Carter (aged only 31) was offered the position of Headmaster in an acting capacity, which he accepted. On 13 January 1904, Carter submitted a memorandum to the College Council, in which he stated that he had gone through the school register and that ‘we have eighty-three boys left.’ So the number of 150 boys mentioned in the prospectus issued the previous year was either an egregious exaggeration or a manifest case of wishful thinking.

Ten days later, on 23 January 1904, Carter sent a handwritten letter to Mr Rockey, in which he provided an analysis of the religious denominations of the boys attending St John’s. The first point he made was that the school did not keep any sort of creed register, with the result that his statistics might not be perfectly accurate. However, he said, in the final quarter of 1903 ‘we had sixty-seven boys in attendance’ – so even the number of 83 given in his memorandum to the Council may have been an overstatement. Of the 67 boys who had completed the previous school year, 51 were members of the ‘English Church’ (i.e. the Anglican Church), while eight were Jewish, three were Dutch Reformed, three were Wesleyan (Methodist), and two were Presbyterians.

Carter alluded wistfully to times when the school had been ‘numerically stronger’, and then proceeded to reflect on the boys’ attitude towards denominational differences: ‘If a boy is a decent chap it does not matter two straws to his school fellows what he believes or disbelieves, they judge him by what they see him to be. In the same way if a boy is “a rotter” he sees trouble and the fact of his professing to belong to the English Church is not going to take the edge off!’

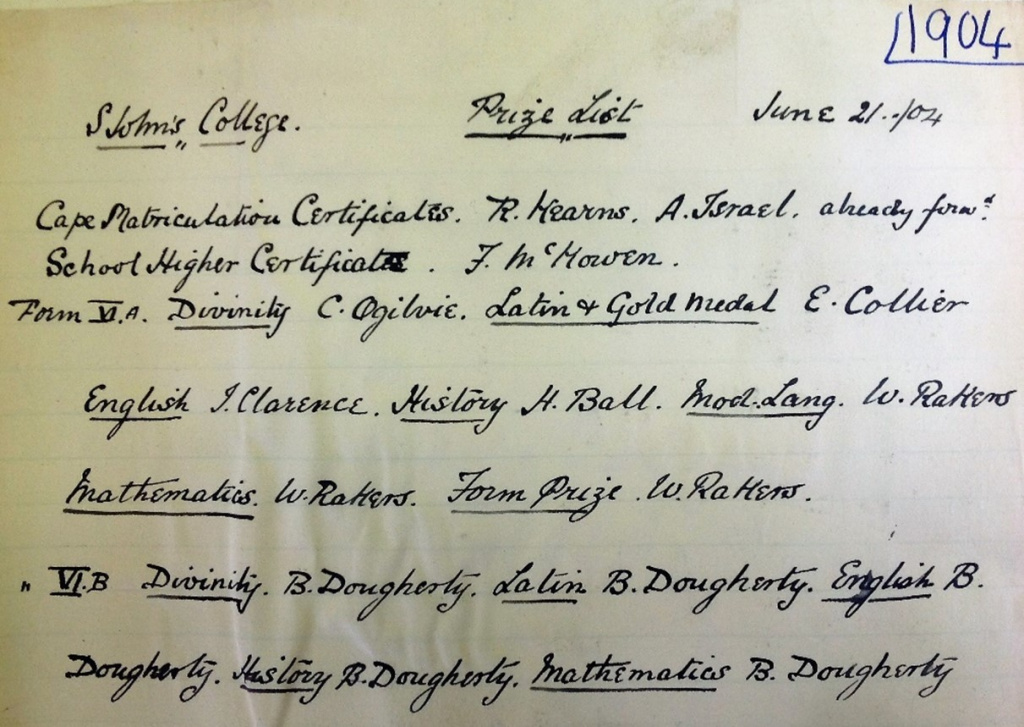

By mid-1904, the number of boys registered at St John’s College had declined further to 54. Still, at the half-yearly prize-giving, the Bishop of Pretoria, William Marlborough Carter (an Old Etonian who had succeeded Henry Bousfield in the episcopal seat in 1902), optimistically said that, before long, St John’s would be one of the best schools in Johannesburg and that, if the English Church could not support the school, it ought to be ashamed of itself.

Meanwhile, Darragh had returned to Johannesburg. Presently he formed the realistic view that St Mary’s parish could no longer bear the burden of supporting the embattled school. Consequently, he supported a proposal that the school be closed. However, in consultation with Archdeacon Michael Furse (also an Old Etonian, who was Chairman of the College Council), it was decided to transfer responsibility for the school from the parish to the Diocese. Thus St John’s became a diocesan college.

In these trying circumstances, it is not altogether surprising to learn that Mr Elliott’s records of the 1903/04 cricket season show that the St John’s team ‘did not this year do so well in the league. … Our school team that year consisted of J. Goch, T. Louw, A. Troye, B. Sims, C. Ogilvie, H. Danziger, E. Collier, R. McKowen, E. J. Hurley, C. Winslow and C. Higham.’

In the ensuing years, impecuniosity and diminishing enrolment numbers left St John’s College in a most precarious position. Mr Elliott wrote about the College’s struggles: ‘Government Schools were opening up, and these provided better buildings and grounds than we could present, also their fees were lower. Consequently S. John’s went through rather bad days.’ Inevitably, these adverse circumstances impacted on the state of the school’s cricket, with its team struggling in the Transvaal second league, although Mr Elliott himself scored 102 for St John’s against Mayfair Cricket Club.

Perhaps it was the weakness of cricket at St John’s that prompted Mr G. W. Johnson, a College master who also held office as secretary of the Transvaal Cricket Union, to enter a composite team, comprising players from various schools, in the T. C. U.’s second-division league and in the Chauncey Cup competition (the club championship for the lower leagues). Several St John’s boys (Alan Fraser, Toby Louw, Cecil Hutchinson, Duncan Solomon, Charles Solomon, Arthur Troye and Gordon Heinekey) played for the Secretary’s Team, together with Mr Johnson himself and Mr Elliott. Another member of the team was Claude Floquet, who matched the all-round skills of his older brother, Bertram: he scored 50 runs and took five wickets against Wanderers Cricket Club in February 1904. He also scored 51 not out for the Secretary’s Team against ‘The Australasians’ (whose team included one G. Washington).

Both Bertram and Claude Floquet went on to play first-class cricket for Transvaal; Claude played a solitary Test match for South Africa against England in 1909/10. Bertram was a good tennis player, reaching the singles semi-finals in the South African national championships in 1914.

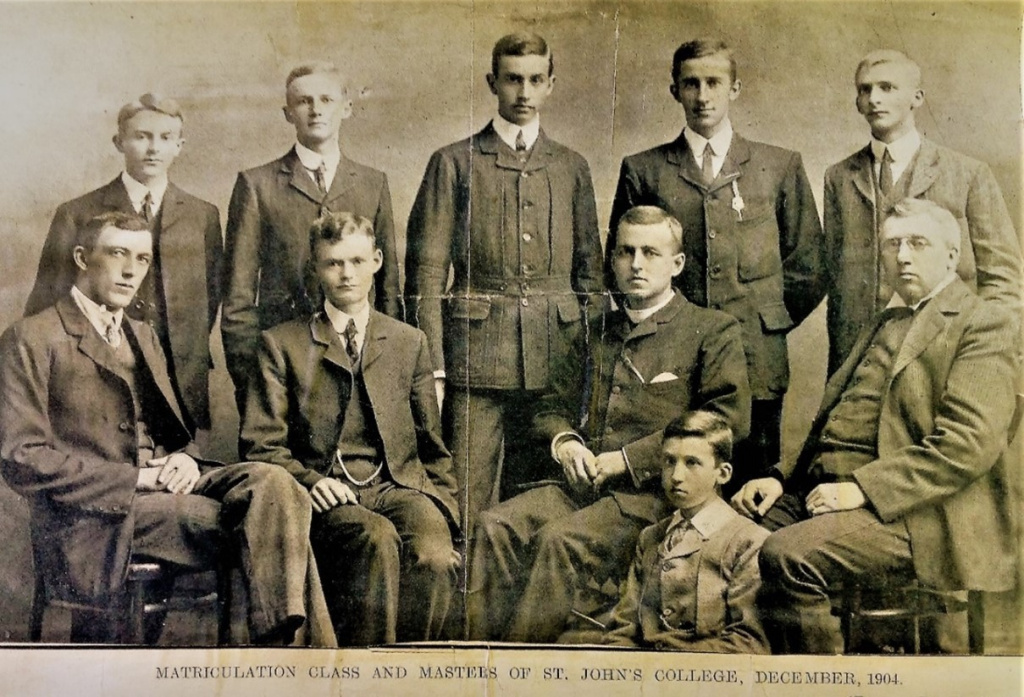

In his end-of-year address in December 1904, the Revd Mr Carter recorded that the number of boys in the school had dropped further to 49. Eleven of the 24 boys who had departed since the beginning of the year had gone ‘home’ to schools in England. Despite the ‘superior attractions’ offered by the government schools on Johannesburg, only three boys had left St John’s for these schools, he said. But – and here was the sting – ‘new boys do not come [to St John’s] in large numbers.’ Although the College seemed to be in extremis, Carter, ever the optimist, drew attention to the fact that the school had a ‘very promising Matric class’ for 1905.

Principal sources:

JOI Agar-Hamilton Transvaal Jubilee: A History of the Church of the Province of South Africa in the Transvaal (1968); H Kidson The History of Transvaal Cricket (1995); KC Lawson Venture of Faith: The Story of St John’s College, Johannesburg (1968); W Macfarlane Greater Than We Know: The History of St John’s Preparatory School (2004); P Venter ‘Die groei van onderwysaangeleenthede in Johannesburg, 1886-1920’ (PhD thesis, Potchefstroom University, 1950); WH Wills & RJ Barrett Anglo-African Who’s Who and Biographical Sketchbook (1905); Transvaal Leader 12 January 1904, 10 February 1904 and 14 March 1904; Rand Daily Mail 22 June 1904; The Star 10 October 1904 and 17 October 1904; Letter of Easter Term 1909; The Johannian All Saints Day 1922, May 1955 and November 1974