by Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

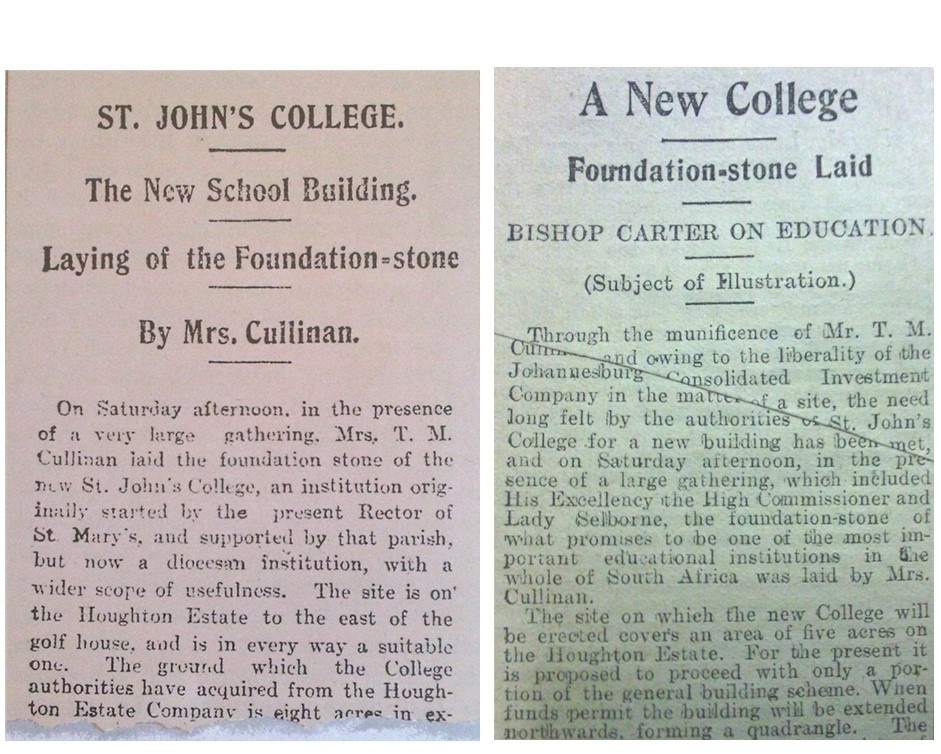

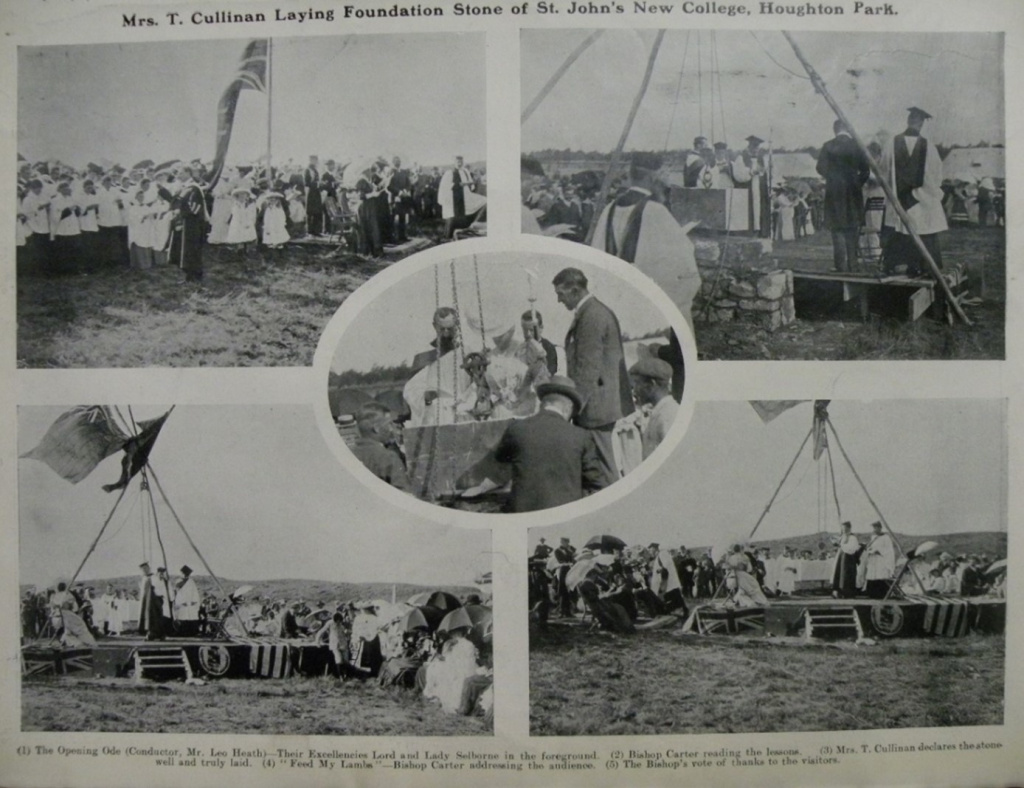

The munificence of Thomas Cullinan, who resided at The View on Carse O’ Gowrie Road (the present headquarters of the Transvaal Scottish Regiment) and who would later sit on the Council of St John’s College, enabled the College to proceed with Nash’s scheme for the development of the new Houghton site. On 12 January 1907, an inauguration service was held in the veld at the new site, where Mrs (later Lady) Anna Cullinan laid the foundation stone. The Scripture readings came from Psalm 84 (‘How amiable are thy dwellings’) and Psalm 127 (‘Except the Lord build the house’). Reports and pictures of the ceremony appeared in The Star and the Transvaal Leader:

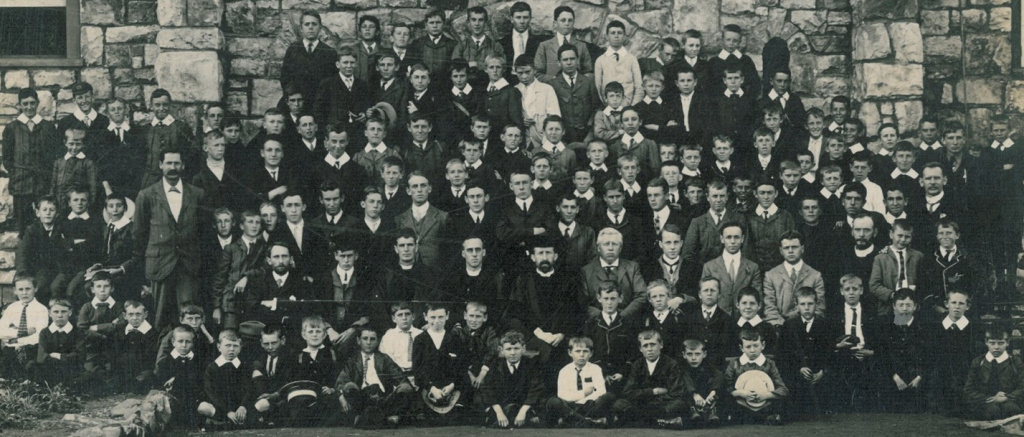

At the beginning of Lent Term, which opened a fortnight after the ceremony held on 12 January 1907, there were almost eighty boys on the St John’s books. Enrolment had nearly doubled since January 1906, when Nash and the Community of the Resurrection had taken over.

On Valentine’s Day, St John’s played cricket matches against Jeppe at Belgravia. In the 1st Xi encounter, Jeppe scored 143 (Lloyd taking three wickets) and, shortly before 7 p.m., dismissed St John’s for 116 (Lloyd 18*, Reid 17, 29 extras). The St John’s 2nd XI won by 24 runs.

The first cricket match at St John’s College’s new grounds in Houghton was played on 16 February 1907, while construction of the new building was still underway. On that auspicious occasion, the St John’s 1st XI (‘certainly the best side the College had so far produced’, in the estimation of Fr Nash) prevailed over Marist Brothers’ College by 52 runs. The St John’s team featured ‘useful’ players like Basil Roseveare and Wilfrid Brown-Constable (who also won the Latin Gold Medal for that year). However, the return match against Marist Brothers, played at the Wanderers ten days later, was lost by 68 runs.

On 4 March, Fr Nash recorded in his diary that he had introduced a ‘satisfecit’ system for boys whose work was unsatisfactory – they were detained (‘by master having cane’) an hour every day and were required to have a card signed ‘S’ or ‘NS’ i.e. ‘Sat’ or ‘Non S[at]’. Although this system has evolved over the years (no ‘master having cane’ has been involved for some decades), it survives in the ‘satis card’ system still being used, albeit sparingly, by housemasters as a mechanism for monitoring the diligence and progress (or lack thereof) by boys whose academic results do not match their potential.

On 9 March, the 2nd XI played their counterparts from Johannesburg College at the St John’s ground in Houghton. St John’s scored 70 and Johannesburg College 41. A week later, the 1st XIs of the two schools met. St John’s was at a disadvantage, the captain of cricket, Hugh Hughes, having left the school earlier in the week. Johannesburg College scored 145/6 and dismissed St John’s for 21 and 57 to win by an innings and 67 runs. To this day, the score of 21 remains the lowest total ever recorded by the St John’s 1st XI. By way of consolation, the St John’s juniors won their game by 20 runs.

To conclude the Lent Term cricket season, the Past v Present match was played at Houghton on 23 March 1907. The Old Boys, led by Stokes, won by ‘a few’. In his Letter to parents at the end of term, Fr Nash stated that St John’s College’s relocation to Houghton would not involve an increase in fees, apart from a termly charge of five shillings for games: ‘Cricket is a rather costly amusement, and parents will be glad to have our games well equipped.’

During April 1907, Fr Eustace Hill C. R. taught Geography at St John’s on a temporary basis. Later in the year, though not yet officially on the staff, he also ‘lent a hand with History.’

Meanwhile, the saga concerning the new site for Johannesburg College continued. On 27 February 1907 the Johannesburg Town Council had adopted a resolution expressing ‘the opinion that the site on the Houghton Estate, provisionally approved by the governing body of the Johannesburg College, is a suitable one.’ The Braamfontein Estate Company had offered three sites free of charge (whereas the site in Houghton approved by the governing body of Johannesburg College would cost £4,800). The non-governmental Witwatersrand Council of Education had voted the sum of £22,500 towards the cost of erecting three secondary undenominational schools, on condition that the government spent an equal amount on the buildings and that the sites were given free. At a meeting of the Town Council held on 17 July 1907, a resolution was moved that the Town Council should defer to the W. C. E. and the ‘authorities’ on the matter of the site for Johannesburg College (which then had 244 pupils). The motion was not carried and, instead, it was decided to refer the matter back to the Town Council’s General Purposes Committee for further consideration.

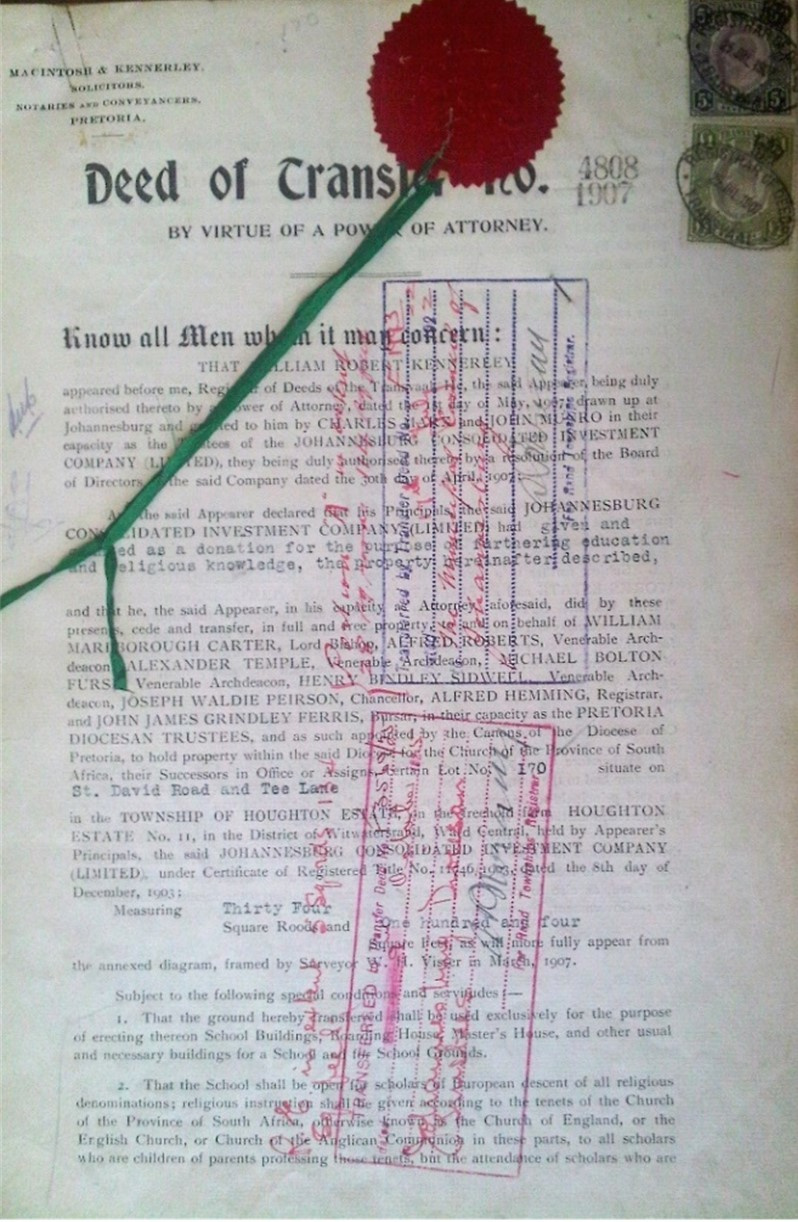

The deeds of transfer in respect of the land in Houghton acquired for St John’s College were registered by the Registrar of Deeds on 30 July 1907. The deeds record that the erven concerned were being transferred from Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Co. to the Lord Bishop, William Marlborough Carter, the Venerable Archdeacons Alfred Roberts, Alexander Temple, Michael Bolton Furse and Henry Bindley Sidwell, Joseph Waldie Peirson (Chancellor), Alfred Hemming (Registrar) and John James Grindley Ferris (Bursar) in their capacity as the Pretoria Diocesan Trustees, to hold the property for the Church of the Province of South Africa.

Registration of transfer occurred subject to the conditions that the ground be used ‘exclusively for the purpose of erecting thereon School Buildings, Boarding House, Master’s House, and other usual and necessary buildings for a School’, and also that ‘the School shall be open for scholars of European descent of all religious denominations; religious instruction shall be given according to the tenets of the Church of the Province of South Africa, otherwise known as the Church of England’ etc.

Thus, although the prospectus issued when the College was established in 1898 had simply provided that applications for admission to the school had to receive the approval of the College Council, the restriction that the school would be open only to ‘scholars of European descent’ was now entrenched in the title deeds. This restriction was derived from clause 2 of the deed of sale dated 9 January 1907 in terms of which J. C. I. had sold the land to the Diocesan Trustees.

On 10 August 1907, the new St John’s College building was officially opened by the High Commissioner for Southern Africa, the Earl of Selborne. In his speech he expressed the hope that St John’s would ‘develop on exactly the same lines as the best Public Schools in England [namely] God first, country second, self last.’ Lord Selborne was accompanied by his wife, Lady Beatrix Maud Gascoyne-Cecil (like him a keen supporter of the work of the Community of the Resurrection), and by his aide-de-camp, Viscount Windsor-Clive. Dignitaries included Professor (later Sir) Walter Raleigh (Professor of English Literature at Oxford), the Revd Fitzwilliam Carter (former Headmaster of St John’s College), Mr Geoffrey Robinson (editor of The Star and later editor of The Times in London) and Colonel Charles Stallard K. C. (later a member of the College Council and of General Smuts’s wartime cabinet).

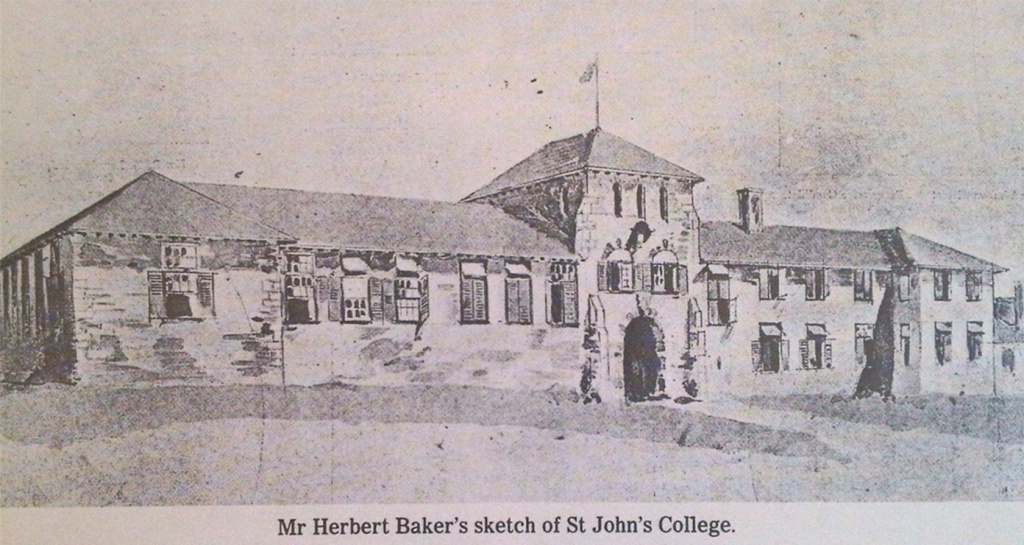

The site for the new building, it was reported in the press, had been chosen ‘with due regard to picturesqueness of surroundings, while externally and internally it has been admirably designed.’ It was also said that ‘the handsome new buildings, which stand on a picturesque kopje on the Houghton Estate, are built of stone from this kopje, and command a magnificent view to the north.’ The singing of the processional hymn was followed by prayer, offered by Dr Carter (the Bishop of Pretoria) in words composed by Fr Nash:

‘Lord God, our Father, Who art Truth and Light and Love, look down in love upon our College of St John; make it to be a home of religious discipline, sound learning, and good will, which may send forth many rightly trained in body, mind and character to serve Thee well in Church and Commonwealth. Supply our wants, and give us such increase as shall seem to Thee good, and let Thine angels drive away all evil from us, through Thy Son, our Saviour, Jesus Christ. Amen.’

This prayer later came to be adopted as the College’s School Prayer.

The Bishop said that the new building was ‘a home both good and substantial’, which he hoped would be ‘a home of culture both in mind and in body’, for which they had to thank Mr Cullinan for his most generous gift, as well as ‘those old Anglican societies’, the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (established in 1698) and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (founded in 1701), both of which had made donations. (In addition, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Fund had contributed £2,000.) The Bishop expressed the hope that the school would be a home for the ‘training of a Christian manhood which would go out into the world ... to do its duty both in Church and in State, to God and to man’. A letter from the Transvaal Colonial Secretary, Mr J. C. Smuts, intimating his sympathy and interest, but regretting his inability to be present, was read. Fr Nash warmly praised the architects, Messrs Baker & Masey, and the builders, Messrs Quayle & Hawley. The proceedings were terminated by the singing of ‘God Save the King’.

In those days, Houghton was on the rustic periphery of the nascent city, and the College’s new location had a decidedly pastoral atmosphere. The only other buildings in the immediate vicinity were three residences. One of these was situated near the apex of what was to become St Patrick Road (near the present K. E. S., which had not yet been built). The second was the clubhouse (predictably known as the ‘Golf House’) of the rudimentary golf course that was the College’s next-door neighbour. The Golf House stood more or less where the Memorial Chapel is now located. It was a wooden structure, designed in an architectural style approximating Tudor Revival, erected on a stone foundation. It was destined to serve first as a residence for the brethren of the Community of the Resurrection, then as a boarding house, and finally as the prep school. To its west, in the vicinity of the present basketball courts, stood another faux-Tudor wooden residence, formally known as ‘The Uprise’ but colloquially called ‘the Paper House’. Once the Golf House had become a boarding facility, the brethren occupied The Uprise, which became known as ‘Community House’.

Years later, the novelist and poet William Plomer O. J. wrote the following about the impression that the school and its new building made: ‘On the brow of a hill, on what were then the outskirts of town, stood St John’s College. … The site of the School was grandly chosen. It had been nobly and simply designed, and built of rough-hewn local stone.’

‘The site was healthy and the view magnificent,’ wrote Fr Alban Winter C. R. ‘In front lay a great stretch of undulating ground with Pretoria some 40 miles away and the great Magaliesberg range of hills in the still further distance but visible on a clear day. There is no school in South Africa favoured with such a site and I doubt if even such could be found in England.’

The school grounds were less expansive then than they are today. The eastern boundary was at Pine Street. The western boundary was in line with Gate House (or the ‘Main Arch’, as it has come to be known in College vernacular). The northern boundary was approximately along the line of Long Walk. On the kopje to the north, looking down from The Wilds, was a stone fort built by British troops during the Anglo-Boer South African War, which was a great attraction for boys’ sorties. Accommodation was offered to boarders at £20 per quarter, and to weekly boarders at £15 10s ‘(without laundry)’.

On 17 August 1907, a week after Lord Selborne had opened the new St John’s building, the Town Council’s General Purposes Committee resolved that one of the sites offered to Johannesburg College by the Braamfontein Company, situated in Saxonwold just to the north of the zoological gardens, was ‘a better site than the Houghton Estate site’ preferred by the W. C. E. and by governing body of Johannesburg College. (Initially, the W. C. E. had opposed the siting of Johannesburg College on the Houghton Estate because St John’s College, in which the Council had also interested itself, was already there. Eventually, however, the W. C. E. accepted the Houghton site for Johannesburg College.)

By October 1907, St John’s College had grown to have a hundred pupils. But there was only one playing field, a ‘rather rough’ gravel expanse located in an area corresponding to the present Mitchell Field. Summer rains washed away ‘tons of soil’ on the sloping field, leaving exposed pebbles and small boulders. Periodically the school was given a half holiday and set to work picking up the pebbles which persistently forced their way onto the surface of the field. Fr Nash offered the boys a small monetary reward for filling a two-gallon tin of pebbles. A tin of that size took a lot of gathering, and inspired budding civil engineers to devise mechanisms for mass production, so the boys ‘broke the bank’. Fr Nash was often seen picking up pebbles and flinging them towards the boundaries of the field – regardless of passers-by.

Two clay cricket pitches were laid on this ‘field’; until 1961, matches were played on matting wickets unfurled on top of these clay pitches. In 1907, the ground was still surrounded by a dusty golf course, hence the names of the streets – Golf Lane and Tee Lane – to the west of the field. One Old Johannian, Guy Bond (Alston, 1914), reminisced:

‘The golf course was one of the worst for lost balls, owing to the long grass and numerous boulders, particularly in the “Valley” and what is now the upper Wilds. As little boys today collect marbles we used to collect golf balls. Periodically the grass was burnt and we used to follow the fire and pick up partly scorched golf balls. As was the case in all inland courses at that time there were no grass greens. Instead they were covered with crushed “Blue Ground” from the Kimberley Diamond Mines.’

Another Old Johannian recalled the following:

‘The school was at that time … situated in the middle of a golf course of eighteen holes, the result of this being that practically every boy in the school became a golf enthusiast. Golf clubs of all sizes and manufactured out of walking sticks, broom handles, and all sorts of weird things were in evidence everywhere. One walked in fear and trembling in those days for we never knew what was coming next and when it did come it was hardly ever that the injured person found out where that one came from. Our cricketers developed into a nation of swipers and the greatest ambition of our batsmen was to hit out of the school ground – in one. The result of this chaos was the suppression of golf in any shape or form’.

Years later another old boy, the author and radio personality Eric Rosenthal (who was at St John’s from 1918 until 1921), also wrote: ‘For some obscure reason which I never discovered, the prospectus of the College contained a regulation: “Boys are not allowed to play Golf.”‘ The ‘obscure reason,’ it seems, is that Fr Nash took a dim view of the boys’ obsession with golf:

‘Our cricket ground is encircled by a danger eighteen holes long, and the sight of loaded caddies and the swinging niblick has exercised a dangerous fascination over some youthful minds. But the fact is, a boy cannot learn cricket and golf at the same time. In golf the art is to lift the ball, in cricket to keep it down; a golf club strikes at an angle of 45 degrees, but a bat has to be straight! Which are no doubt reasons why Scotland – let it be whispered gently – can’t play cricket. ... But cricket and football are the games for schoolboys, to teach them to play for their sides, with other virtues. Golf is for men.’

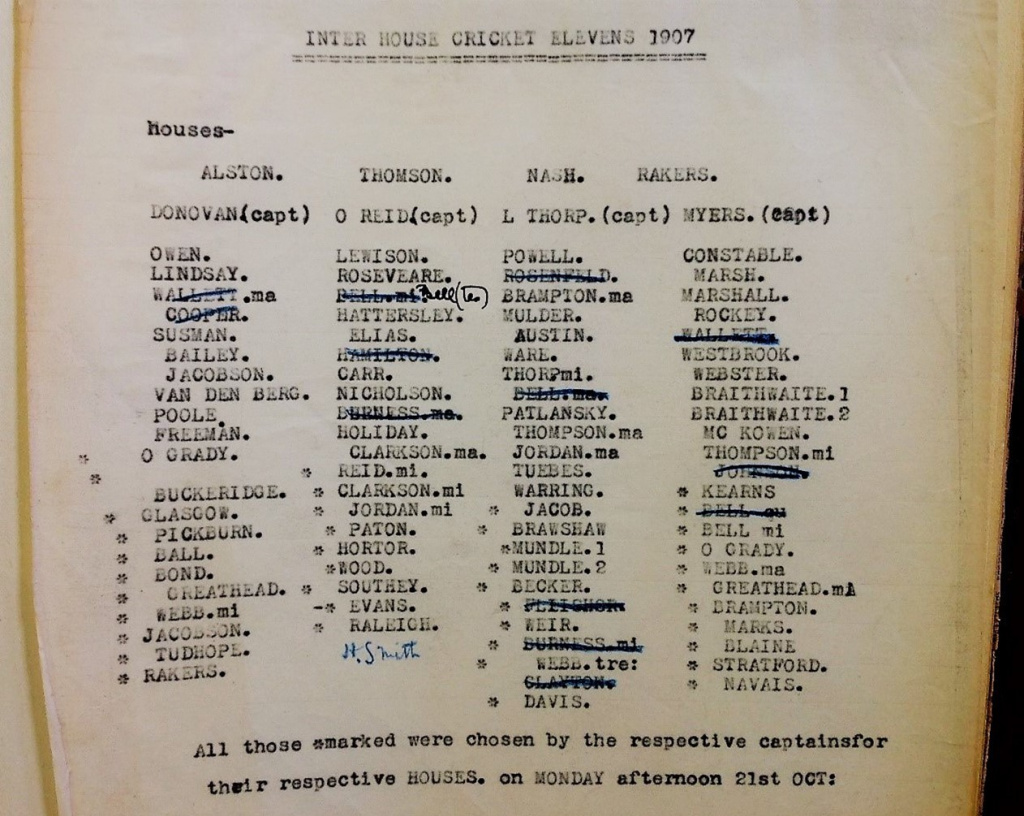

It was on this ‘playing-field of crimson earth, with outcrops of soft shale and planted round with pine-trees and macrocarpa hedges’ (in the words of Plomer), that inter-house cricket matches were played between the houses of Alston, Thomson, Nash and Rakers on Monday 21 October 1907.

In 1928, when the Old Johannians established their own sports grounds on the fringe of Norwood, it was said that the soil there was of a ‘dark restful colour that seems to ask for grass to be planted and … it will not be asking for grass very long. At present, perhaps, your cricket boots will gather a few pounds of heavy black soil in the wet weather, but is not that preferable to the fearful red dirt acquired on the school grounds in earlier years and which has condemned us to eternal bathing ever since.’ It was suggested that, instead of ‘the Old Johannian Ground’, it should be called ‘Nash Park’, which would sound more dignified and ‘would perpetuate the memory of a very worthy gentleman, of whom we all have the very highest regard.’

St John’s played against Jeppe at Belgravia on 20 November 1907. St John’s declared at 141/5 (Bell 62*, Roseveare 33), leaving Jeppe 1¼ hours to get the runs. Jeppe managed to do this just on the stroke of time, and graciously acknowledged that they were fortunate in that, but for the sporting way in which the St John’s fielders hurried to their places between overs, Jeppe would not have had sufficient time to win. Marshall and Thorp took two wickets each in the Jeppe innings of 143/5.

On 29 November 1907, a Johannesburg Schools XVIII played against a T. C. U. XII. The Schools team comprised players from Johannesburg College, Jeppe, Marist Brothers, St John’s and Park Town School. Three St John’s boys, Bennett Donovan, Basil Roseveare and Harry Marsh, were chosen for this team. The schoolboys won the match by 82 runs. Around the same time, little Guy Nicolson scored 64 for St John’s College III against Johannesburg College III.

The annual match against the Fathers’ XI was played on 30 November 1907. Batting first after a rain-delayed start, the Fathers scored 118/8. Mr J. Reid scored 63*, which included the first six hit on the new St John’s ground. Marshall took three wickets. The College XI batted with excellent judgment to clinch victory by three wickets (Donovan 38, Owen 22).

In Strenue, A. P. Cartwright’s history of King Edward VII School (as Johannesburg College later became known), reference is made to ‘an astonishing performance’ that occurred at this time in an under 13 match between Johannesburg College and St John’s: ‘In this match one of our adversaries performed the remarkable feat of taking 5 wickets with 5 consecutive balls. But [the match report] fails to give the name of the young prodigy who set up this record!’ The ‘young prodigy’ was Harry Freeman (Alston, 1911). In fact, he not only took five wickets in five balls; he took six wickets in seven balls (all the batsmen being bowled) to save a desperate situation for the St John’s juniors against their counterparts from Johannesburg College. At the annual prize-giving held on 26 December 1907, Freeman was awarded a special prize of a cricket ball in recognition of his achievement. Basil Roseveare received a bat, presented by Mr Rockey, for having scored a century. Other prize-winners included Louis Thorp, who won the class prize and the mathematics prize for Form V, and Oswald Reid, who won the class prize and the Latin and mathematics prizes in Form IV.

Principal sources:

CR Diamond Jubilee Book (1952); AP Cartwright Strenue – The Story of King Edward VII School (1974); JW Horton First Seventy Years: 1895-1965 (1968); KC Lawson Venture of Faith: The Story of St John’s College, Johannesburg (1968); N Mosley The Life of Raymond Raynes (1963); W Plomer Double Lives (1943); W Plomer The South African Autobiography (1984); P Randall Little England on the Veld: The British Private School System in South Africa (1982); E Rosenthal Memories & Sketches (1979); University of the Witwatersrand, Historical Papers Collection, Records of the Church of the Province of South Africa: St John’s College, 1907-1964 (AB630); P Venter ‘Die groei van onderwysaangeleenthede in Johannesburg, 1886-1920’ (PhD thesis, Potchefstroom University, 1950); A Wilkinson The Community of the Resurrection: A Centenary History (1992); A Winter Till Darkness Fell (1962).

The Star 19 January 1907, 18 July 1907, 17 August 1907, 26 December 1907; Transvaal Leader Weekly 19 January 1907, 17 August 1907, 21 September 1907; Rand Daily Mail 21 January 1907, 18 July 1907, 12 August 1907, 25 November 1907, 2 December 1907; Jeppestown High School Magazine December 1907; Transvaal Weekly Illustrated 30 November 1907, 28 December 1907

St John’s College Letter of Lent Term 1908; Letter of Lent & Easter Terms 1912; Letter of Lent & Easter Terms 1913; S John’s College & the War Third Series (May 1916); The Johannian Michaelmas 1923, All Saints Day 1927, Advent 1928, October 1942, September 1944, April 1947, May 1963, November 1971, February 1980