by Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

It might be thought that the First World War was a conflict waged mainly in the trenches of Belgium and northern France and that, for the St John’s College community, it was a remote occurrence with little immediate significance. However, that would be a distorted perception. By the beginning of 1915 already about a hundred Old Boys (including some very recent Old Boys) were away on active service, as were many brothers and fathers of St John’s boys. Most of them were in German South West Africa but already some were in distant Europe.

The Headmaster, the Revd Canon James Okey Nash, compiled letters sent by these soldiers from their far-flung whereabouts in which they recorded their impressions and observations (often in very stolid, matter-of-fact terms). In the case of men involved in the campaign in German S. W. A., these missives frequently focused on the privations associated with being on manoeuvres in such arid territory.

Private Adrian Tyrrell, who had been at St John’s College as recently as 1913, was with the Transvaal Scottish in German S. W. A. In January 1915 he sent a letter in which he reflected that people might look down on South Africa because it had not (yet) sent thousands ‘to help in Europe … whereas she’s got far more reason to be proud of herself than Canada and Australia, because a great part of her population were England’s great enemies twelve years ago.’ He mentioned that he had seen Fr Eustace Hill C. R. of St John’s College at Communion and that he was ‘looking worn. He works hard for us all, and never thinks of himself.’ Tyrrell observed stoically that inconveniences such as thirst and sandstorms ‘only last a certain time, and when they are over you come up smiling and wonder how you ever came to be such a fool as to feel “I wish I’d never left home”.’

In some respects, of course, school life did continue as before. For example, the College 1st XI had a home fixture against Jeppe High School on 10 and 13 February. St John’s won the toss and sent Jeppe in to bat. They scored 95 all out, thanks mainly to a 44-run partnership for the eighth wicket. Victor Langford (Hill) took 4/14, and Joffe maior took three wickets. St John’s collapsed to 21/3 but Eric Slade (Nash) and Langford stopped the rot and took the score to 90/3 at stumps, Langford having reached 50. On the second day, rain fell in torrents until three o’clock. Perhaps for that reason, Langford did not put in an appearance with the result that, when play resumed, Jeffrey Sacke (Thomson) went in with Slade. They secured victory, Slade going on to score 68 and Sacke 22.

Harold Gillman, who had been at St John’s in the years immediately after the Anglo-Boer South African War, and who had subsequently played in a few Past v Present cricket matches, was now a motorcycle dispatch rider stationed at Swakopmund in German S. W. A. In a letter dated 2 March addressed to Fr Nash, he said that he had travelled some eight thousand miles in four months, including a 400-mile ride through Namaqualand. He mentioned that, in the course of his odyssey, he had encountered several St John’s alumni, including John Rockey (Rakers, 1908), who was with the Imperial Light Horse; Cracroft Marshall (Rakers, 1908), and William Currie (1904), who was with the Transvaal Horse Artillery. He referred to them as ‘Old Johnians’, which indicates that the term ‘Old Johannians’ (by which Old Boys would eventually become known) had not yet gained general currency.

On 10 and 13 March, King Edward VII School defeated St John’s by eight wickets. St John’s scored 110 (Slade 44), to which K. E. S. replied with 145, Edward Wimble (Hill) taking seven wickets. In the second innings, St John’s declared at 118/5 (Wimble 48, Joffe maior 43). Despite the loss of two early wickets, K. E. S. reached the required target easily.

The match between St John’s and Pretoria Boys’ High School was drawn, St John’s scoring 217 (Joffe maior 63, Wimble 56, Slade 36) and Pretoria 138/5 (James Butler 3/21).

Despite this semblance of normality, the reality of the War would have been a constant presence in the minds of members of the St John’s community, for many of whom the Anglo-Boer War would have been fresh in the memory. On 9 April 1915, Private Herbert Sacke (Nash, 1914), who was with the Rand Light Infantry, wrote to Fr Nash from German S. W. A., saying that it was ‘impossible to form an opinion as to how long the war will last, but everyone is optimistic.’

On 6 May, Fr Hill sent a letter from Swakopmund to Herman van der Linde, the star swimmer in Hill’s House, who had previously written to his absent Housemaster to keep him posted about events at school. Fr Hill mentioned that a St John’s gathering, attended by thirty Old Boys, had been held at Swakopmund two days earlier. Captain Morris Norton had been the ‘chief organiser’ and Lieutenant Leonard Durham had been ‘chief entertainer’. Both were St John’s veterans, having been at the school in the days of the Anglo-Boer War.

Fr Hill then embarked on a revealing disquisition: ‘Faults in schoolboys are very apparent in soldiers. I believe slackness is the worst vice of all, and father of a prodigious family. For God’s sake kick slackers. An active promoter of evil is not such a beast as a grousing sluggard who scrimshanks … He finds it hard to tell the truth and runs the chance of becoming a first-class liar, as well as a toad in a hole. So make war on all slackers, whether lazy in school or field.’

He concluded by saying that he longed for the College football team’s ‘success gained by hard work if not by talent. Games are won by best-trained teams so often, and not always by most talented, so let’s hear our boys were going strong up to time and won the shield by real hard grind.’

In a letter dated 10 May written from London, Oswald Reid (Thomson, 1910) reported to Fr Nash that he had been promoted to First Lieutenant in the King’s Liverpool Regiment. He referred to the battles at Neuve Chapelle in France (10-13 March 1915) and Ypres in Belgium (April-May 1915) and said that in little over two months his regiment’s numbers had been reduced from thirty officers and a thousand men to seven officers and about 300 men. He spoke about the horrors of the poison gas used by the Germans at Ypres, about the terrible loss of life, and about the ‘marvellous imperturbability and cheerfulness of the British soldiers [who] face death as if it was a common occurrence.’

On 13 June, Fr Hill wrote from Usakos (north-east of Walvis Bay and Swakopmund) that General Botha had told them that five weeks would end the campaign in German S. W. A. ‘if all do their duty.’ Two weeks later, Fr Hill reported from Omaruru, further to the north, that rumour considered anything possible – three days or three months. However, he did not mind if the Germans had to be chased all the way to Victoria Falls ‘as this country in winter is worth trekking through.’

Fr Hill recounted that the Belgian Oblate priest at the convent in Omararuru had lent him their church for Sunday Mass. However, on the Sunday morning the South African soldiers had been ordered to march, with the result that Hill had nobody with whom to celebrate Mass. The Oblate Father came, ‘so I was able to have my Sunday Eucharist. Latin was what we resorted to when his English and my gesticulations failed to convey our wishes. Any old Dog Latin suited our purpose, but why on earth didn’t Caesar eat marmalade or drink coffee, or Livy introduce a little conversation between two of his military chaplains instead of leaving it to us to create a new line of Latin Authors?’

Fr Hill also mentioned that, by now, he had sampled most of the local game, from gemsbok and koodoo to stembok (sic), hare, guinea fowl and goat. He had also seen ostrich and antbear being cooked ‘but have not fancied either.’

Meanwhile, on 15 June Leonard Denny (Alston, 1911), who was with the Transvaal Horse Artillery, had written to thank Fr Nash for the copy of the Headmaster’s Letter that had reached him at Swakopmund shortly before they had departed on the advance to Windhoek. Denny described the soldiers’ hardships and thirst as they slogged through the Namib. Trooper William Ogilvie (Alston, 1912) of the Imperial Light Horse also described the trek as ‘simply too awful for words,’ both for the men and their horses, with very meagre rations and no food for the horses. Gunner Rupert Pilkington Jordan (Nash, 1911) of the Transvaal Horse Artillery provided a similar description of an expedition across the Kalahari, which was ‘an experience I should not care to go through again. It was pitiable to see the horses; for they suffered terribly from lack of water.’

The College’s first football team (captained by Edward Wimble) suffered severe depletion in its ranks due to injury, illness and departure to enlist for military service. This translated into disappointing results: defeats to Jeppe (1-4) and Marist Brothers’ College (1-3) and a draw to K. E. S. (1-1).

By contrast, the younger football teams enjoyed successful seasons, coming tantalisingly close to champion status. The second league (under 15) team ended second in their division, winning eight matches, drawing to Jeppe and losing only to K. E. S., and scoring fifty goals in the process while conceding only eleven.

The third league (under 13) team performed even better: they went unbeaten in their division, winning eight and drawing two games. This included a 3-0 victory over K. E. S. Thus the team qualified to play in the league final against Jeppe Central at the Wanderers. The match ended in a 2-2 draw after extra time. This led to a replay, which resulted in a goalless draw after extra time; ultimately, after a further period of extra time, Jeppe Central won 1-0 to claim the shield.

The inter-house football competition was won by Hill’s House (captained by Victor Langford), who had one more point on the log than Thomson’s House.

As it turned out, the South African military campaign against Germany in South West Africa continued until 8 July 1915, when the Germans surrendered. Fr Eustace Hill returned to Johannesburg in August. On 1 September, he gave a talk about the campaign, and a chaplain’s view of it, to the St John’s boys. However, he was not to be back at St John’s for very long.

The annual athletic sports took place on 11 September. A great crowd was in attendance. Although there was no very distinguished record-breaking performance, there was keen competition. Of the foot races, the mile was the best event. It was won ‘in splendid style’ by Maurice Epstein. Thomson’s House won the House Relay race over 880 yards, but the Headmaster’s House won the House Championship. Johannes Roelofsz (Thomson) (who was also a fast centre forward in the football first team) won the victor ludorum prize. At the Inter-High School Sports held later in September, Epstein ran the mile in 5 minutes and 3 seconds to win the silver medal.

The Old Boys’ Dinner was held at the school on the day of the athletic sports. It was decided not to arrange a dance. In view of the fact that many Old Boys were absent on active service, the turnout was lower than usual. Still, there was a fair attendance, with some men in uniform. Fr Nash noted that there was a ‘great race’ on among the Old Boys as to who would be the first to send a son to St John’s. Already a few nephews of Old Boys were at the school.

The Debating Society, which had been in a state of dormancy for a year or two, displayed new signs of animation under the guidance of Mr Wrathall. On 13 September, Jack Greathead (Alston) proposed the motion ‘That this House believes in Ghosts’. He defined ghosts as ‘the visible, or audible, working of the supernatural, especially connected with the ancient belief that certain spirits of the departed are condemned for a time to haunt the spots where they have lived or acted on earth.’ Edward Wimble (Hill) said that ghosts were ‘exhalations from churchyards or the invention of the nerves and imagination.’ Leslie Urquhart (Thomson) argued that haunted houses were the creation of smugglers and forgers who desired privacy. After an entertaining debate, the believers prevailed over the sceptics by 30 votes to 20.

Not all debates were of such a frivolous nature. The War generated much controversy, and this was reflected in debating motions. On 29 October, Geoffrey Smart (Nash) proposed ‘That America is justified in remaining neutral’. In opposition, Arthur Williamson (Nash) countered (with the forensic skill that was to elevate him to the bench of the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court many years later) by asking whether England would have been justified in remaining neutral and seeing Belgium crushed. The motion was defeated by 8 votes to 35: ‘and that,’ said Fr Nash, ‘is how we settled up the United States and President Wilson.’

The 1st XI was relatively inexperienced on account of the absence of three senior players who enlisted for military service during the second half of the year. One of these was Leslie Urquhart, the captain and Senior Prefect (‘a kindly, courteous boy … a sound defensive bat’), who went with his father, Dr Urquhart, in the Medical Corps to German East Africa. The loss of these players accounted partly for a ‘rather disappointing season’ (losing to K. E. S., Jeppe and Pretoria, but beating Marist Brothers’ College). The poor results were all the more disappointing as the team included several very capable players who simply did not live up to expectations. Still, Fr Nash commented philosophically, ‘we have had some very successful seasons, and must take a bad one when it comes.’

On 14 October 1915, the 1st XI played against a team of clergymen, who were attending the Anglican Church’s synod. The men of the cloth were captained by the Bishop (who took one wicket and scored 1*, having insisted, as always, ongoing in at number 11). The Clergy XI also included the Venerable Archdeacon Roberts (‘venerable is no merely ecclesiastical title: once a fine cricketer and captain of Pretoria, he still could put to shame many a younger man’). The match was won by the schoolboys.

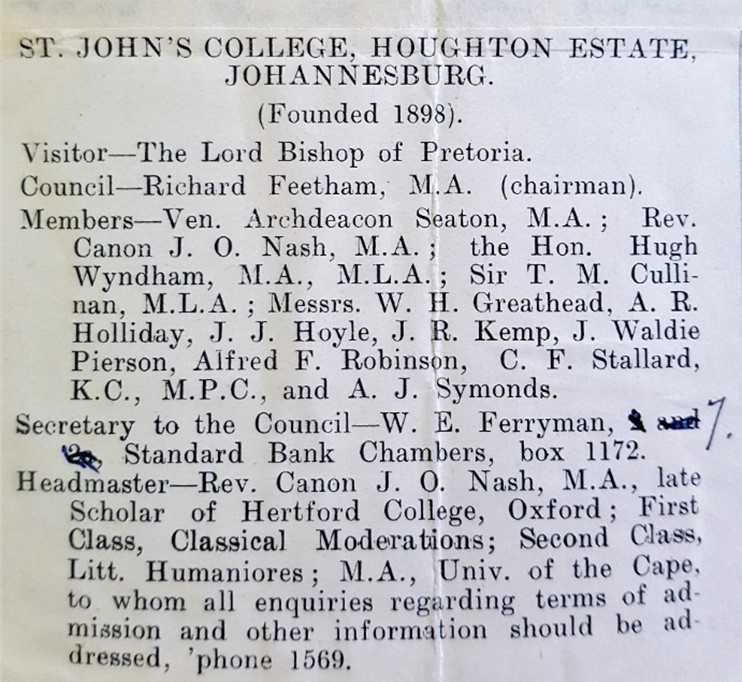

In the parliamentary elections held on 20 October, the chairman of the College Council, Mr Richard Feetham, was returned as M. P. for Parktown. Another member of Council, the Hon. Hugh Wyndham was re-elected M. P. for Turffontein. A former Council member, Mr William Rockey (who had been prominent in the launch of the College in 1898 and in seeing it through the troubled years after the Anglo-Boer War), was elected in Langlaagte. Mr Patrick Duncan (‘a constant friend and regular prize giver) was elected in Fordsburg. All of these Parliamentarians were members of the Unionist Party, an Anglo-South African pro-Empire party whose objective was to maintain the ‘sacred tie’ with Britain, and which later merged with the South African Party led by General Smuts.

The school’s annual gymnastics display was held in the Wanderers Club’s gymnasium on 3 November before a ‘tremendous gathering’. The boys all played up splendidly, wrote Fr Nash, to the delight of the audience. The wrestling bout perhaps aroused the greatest enthusiasm. Leonard Hughes (Hill) gave a wonderful exhibition with the clubs and made the audience shiver with his daring feats on the horizontal bars. Fr Nash mentioned that Leonard’s brother Hughie (1st XI captain, 1907, and former national amateur heavyweight boxing champion) ‘has just given his life in German East.’

Fr Nash also wrote: ‘I own this [gymnastics] display is a thing I like very much, for every boy in the school from highest to lowest, who is physically capable, takes part.’ He recorded that the headmaster of K. E. S. had written to say that he had enjoyed the evening immensely: ‘I have never seen a whole school … acquit themselves so admirably; the discipline and precision of movement were excellent.’

Victor Reid (Thomson), a younger brother of First Lieutenant Oswald Reid, won the individual gymnastics competition.

In another debate, held on 19 November, Jack Greathead moved ‘That the Railway is the most useful invention of the last hundred years.’ Opponents of the motion spoke in support of aircraft (Edward Wimble), the petrol motor (Geoffrey Smart), and wireless telegraphy (Reginald Manners). Little Errol Browning, in his maiden speech, pleaded for the fountain pen, ‘with which lines could be written as soon as given, while nobody could take your nib!’ Martin Boon gave his vote for flycatchers. In the end, the majority of the House voted for the Railway.

St John’s played against Jeppe at Kensington on 20 November, play on the first day having been impossible due to a heavy downpour. Jeppe scored 219/6, Wimble taking three wickets and Langford two. St John’s were dismissed for 148 (William Randall 27, Langford 25). In the drawn 2nd XI match, Norman Brampton scored 87 and James Baker took 5/20 for St John’s.

On 24 and 27 November, K. E. S. outplayed St John’s, winning by an innings and 62 runs. McCubbin ‘was very much on his day’ and scored 102* in the K. E. S. innings of 259, Wimble again taking seven wickets. St John’s were bowled out for 68 (McCubbin 6/10) and 129 (Rankin 27, Randall 25). Fr Nash regarded the K. E. S. team as ‘one of the best school elevens I have seen’.

Meanwhile, the College had obtained a loan of £4,000 from the Witwatersrand Council of Education to supplement the funds raised for the first phase of the Upper School building project. On 16 December, the ‘new College wing’ was blessed by the Visitor, the Bishop of Pretoria, the Rt Revd Michael Furse. It was built by John Barrow & Son according to the design of Herbert Baker and Frank Fleming. In the fullness of time, Pelican Quadrangle was to take shape from this development. The new wing comprised two dormitories (‘splendidly lofty and airy’) of thirty beds each, seven classrooms, two masters’ rooms, matron’s rooms, bathrooms and a boarders’ common room. As had happened a year before, when Viscount Buxton had come to lay the foundation stone, a procession marched from the old school building to the new one, singing ‘Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones’.

The Prep School (which now numbered 140 boys and five teachers, headed by Miss Constance Thomas) relocated from the Golf House to the original school building, erected in 1907.

The Crypt Chapel (‘a small stone building with round domes like a miniature Russian Cathedral’) was also opened, with a Choral Eucharist. ‘A comely little building it is,’ wrote Fr Nash, ‘which has won much praise for Mr Fleming, the architect; and wonderfully resonant.’ Built at a cost of £560, the Crypt Chapel could seat nearly a hundred people. It was the gift of an anonymous donor (probably the Community of the Resurrection itself) and, according to the grand blueprint of Baker and Fleming, was intended to serve as substructure to the College Chapel to be built in due course.

Fr Nash could write with pride: ‘Now the buildings form one side and a half of a projected quadrangle, the east side of which is designed to consist of a hall and chapel. This chapel would stand right over the steep descent of the ridge and would require a substructure. This is what the crypt is for, and it provides meantime a beautiful little chapel that can hold a hundred. This term, with 70 new entries, we have reached 350; so the whole school cannot use the crypt. But it serves splendidly for the boarders (who now number 75) and the masters.’

On the same occasion, Fr Nash made another announcement: a handsome donation by the Bishop’s chaplain, the Revd H. L. Bell, augmented by a gift from Winchester College, had enabled St John’s to acquire a bell, cast for the school by experts in Loughborough, Leicestershire. An elegiac couplet, composed by Fr Nash and Sir Patrick Duncan and inscribed on the bell, explained its historic significance: ‘Pactum servavit, Germanos Botha fugavit; solve fidem moneo, fortis disce sono’ (I toll: Botha has kept his pledge, he has put the Germans to flight; keep faith, I warn, learn to be brave).

Mr Feetham, struck by the concordance between the nature of the gift and the donor’s surname, added an Alcaic stanza to the other side of the bell: ‘Quod tuos ad sacra vocet, Beate, sive ad assuetum pueros laborem; nominis donum similis dicavit presbyter hospes’ (Blessed [St John], a visiting priest has dedicated a gift of like name; it calls your boys to prayers or to their usual work).

Fr Nash also expressed gratitude to donors who had given the school a Red Cross flag and a Union Jack. He said that the school had been flying the Allied colours every day: French, Belgian, Russian, Italian, Serbian, Portuguese and British.

The Past v Present cricket match was played the same day. The Old Boys were captained by Frank McKowen. The College 1st XI scored 170. In reply, the Old Boys scored 130/8, the match ending in a draw.

The Visitor’s wife was the guest of honour at the Prize-Giving. ‘It was a happy omen at the opening of our new building to have Mrs Furse with us. For she would recall, as we did, how she visited us for the same purpose in 1906, when St John’s had but few boys in [corrugated] iron buildings alongside the Union Ground in the town, with no playground but a back yard.’ Leslie Urquhart received the form prize for Form V, as well as the English and Science prizes. Geoffrey Smart won the French and Mathematics prizes. Mrs Furse handed the Old Boys’ bat for the best batting average to Samuel Joffe (who also received the Form V prize for Dutch), and the ball for the best bowling average to Edward Wimble (‘a fine bat and a good bowler’, a prefect and a fine actor, having played Cassius in Julius Caesar and the King in Henry IV).

It is interesting to note from the prize list that the form today known as Upper IV was referred to as ‘Shell’ – not an uncommon form denomination in English public schools but not one that enjoyed any longevity at St John’s.

Fr Nash expressed appreciation for the compliment of having been invited to distribute the prizes at the K. E. S. sports day: ‘We all of us understood it as the expression of the wish that the two schools, close neighbours as we are, and rivals as we cannot fail to be, should be friendly rivals. The competition is bound to be warm, and there is no harm in that if both sides play the game, and this invitation marked the kindly good wishes of King Edward’s.’

There were several changes in the composition of the school’s staff contingent. Mr Reginald Harding took leave of absence for military service in Europe. Fr Eustace Hill, having served as Anglican chaplain to the South African forces in German S. W. A., was selected by the Archbishop of Cape Town to accompany the Overseas Force which was departing for Egypt en route to the Western Front. Mr Nash (no relation of the Headmaster), a ‘most capable’ science and mathematics teacher, left St John’s at the end of 1915 ‘for Government service’. On the other hand, Mr Muller (who had been teaching Dutch to the senior boys since the death of Mr Rakers, and who was, besides, ‘a very capable mathematician and always an admirable disciplinarian’) would henceforth take all the Dutch classes. Mr W. H. Miles B. A. (Jesus College, Oxford), who had to his credit a first in Mathematical Greats and a second in Mathematical Mods, joined the staff.

After the campaign in German S. W. A. had been concluded successfully, the focus shifted to German East Africa – the German colonial territory in the African Great Lakes region: Tanganyika (mainland Tanzania), Rwanda and Burundi. In December 1915, Victor Langford, ‘a good bat and an excellent fast bowler’ who had taken over the captaincy of the 1st XI in Advent Term, enlisted with the 6th S. A. Horse, a mounted infantry regiment, and went to German East Africa. He was thanked, on his departure, for leaving a thank-offering of two handsome turned wooden candlesticks for the Crypt Chapel altar.

Others who enlisted immediately after the end-of-year exams included Edmund (‘Teddy’) Goodwin (‘our giant, 6 feet some inches, a most useful, good-hearted Prefect … examinations were not his strong point’), Eric Slade and Bissett Halliwell, all of whom had played for the 1st XI in 1915.

By the end of 1915, in excess of 120 St John’s Old Boys were dispersed across several theatres of war. Many were in German East Africa. Gilbert Reynolds (Nash, 1912) had gone with the S. A. Rifles up the Zambesi River and Lake Malawi to northern Nyasaland. James Butler (1915) had entered the Inns of Court Officers Training Corps in England. Charles Ogilvie (1904) had received his commission in the Middlesex Regiment. Several Old Boys were training with the Grenadiers at Borden and Aldershot in Hampshire. They included Dudley Fynn (1914), Dudley Moses (1914), Allen Weir (Nash, 1913), Cecil Murray (1914), Atherton Rawstone (1914), James Robinson-Oddy (1913), Reginald Egerton Bissett (1905) and Cracroft Marshall (Rakers, 1908).

In November 1915, Private Fynn wrote to Fr Nash that the action of throwing bombs ‘is the same as that of bowling in cricket, but I never pretended to be an extra good bowler!’ He also mentioned that Fr Hill was with them and had ‘started work in his systematic way.’ Early in December, Egerton Bissett wrote that he was meeting St John’s chaps nearly every day. ‘Fr Hill is still knocking round doing good. He is a fine chap. The other day I was not feeling well, so went to the quiet room (at the Soldiers’ Home). He turned up and gave me a glass of milk and a bun. It was jolly decent of him.’

Also early in December, Lance-Corporal Bernard Stokes wrote: ‘This little England is a glorious country and well worth fighting for, and any sacrifices we can make are well worth making with a good heart and in the full knowledge that it is not in vain. … The fine old traditions built up before us, our freedom and fairness compared with other nations, and the grand spirit which is being shown so quietly.’

Shortly before Christmas, Fr Hill wrote to Fr Nash from Borden: ‘Moses and Fynn have joined the Churchmen’s Society, and are a great help to me. … I am so glad to find two S. John’s men leading like this.’ He expressed regret that each soldier would be receiving a quart of beer for Christmas dinner: ‘Three glasses might do, but four; those who don’t drink four leave five for those who do. This worship of freedom fails to appeal to me. I wish we could freely agree to curtail our liberty to license.’

The school’s external examination results at the end of 1915, although respectable by contemporary standards, were decidedly modest by modern expectations. Seven (four of them only 16 years old) out of eleven candidates from St John’s passed the Cape Matriculation. None did so in the first class. All the St John’s candidates passed in English, Latin, Dutch and Mathematics. So too in the Transvaal School Certificate (usually written at Lower V level) and the Cape Junior Certificate (written at Upper IV level), not a single St John’s boy achieved a first-class result, although their marks in English and Mathematics were generally very good. In the Cambridge Preliminary (written at Upper IV level), Libero Fatti passed in the two compulsory subjects (arithmetic and dictation) as well as eight additional subjects, while Iorweth Griffiths did so in seven additional subjects.

Principal sources:

KC Lawson Venture of Faith: The Story of St John’s College, Johannesburg (1968); W Macfarlane Greater Than We Know: The History of St John’s Preparatory School (2004); Alban Winter Till Darkness Fell (1962)

St John’s College Letter of Trinity & Advent Terms 1915; S John’s College & the War August 1915; Jeppe High School Magazine June 1915 and December 1915; King Edward VII School Magazine June 1915 and December 1915; The Pretorian III 2 (1915)