by Dr Daniel Pretorius, Chairman of the Heritage Committee

The discovery of gold and the birth of Johannesburg

The early history of St John’s College is entwined with that of the city of Johannesburg. In turn, the history of Johannesburg must be seen in the context of the discovery of gold in 1886. Until then, the area known as the Witwatersrand had been an insignificant region in the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (Z. A. R.), the Boer republic in the Transvaal territory on the Highveld.

San peoples had first inhabited this region. By the fifteenth century, migrants from east Africa had settled here. By the time the Dutch East India Company set up its victualling station at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652, Sotho-Tswana communities dominated the area north of the /hei !garib (the ‘drab’ or ‘murky’ river – the Vaal, as the name would later be translated by European explorers). These peoples had herds of livestock, they planted crops, and they mined and smelted copper, iron and tin.

Professor Revil Mason O. J. (Thomson, 1946) explored the Witwatersrand’s pre-colonial history. His archaeological work exploded the ‘empty land’ myth, according to which the region was devoid of human habitation prior to the arrival of European settlers. In his publications Prehistory of the Transvaal: A Record of Human Activity (1962) and Origins of Black People of Johannesburg and the Southern Western Central Transvaal AD 350–1880 (1986), Professor Mason demonstrated the extent of social and economic development in the area before Europeans set foot here.

Late Iron Age sites, dating from between the 1100s and the 1700s, contain remnants of Sotho-Tswana mines and iron smelting furnaces, indicating that the area had been exploited for its mineral wealth long before the advent of Europeans. Archaeologists estimate that gold was mined in the Limpopo area from the 1500s.

So it came as no surprise when gold was discovered in the Transvaal. In 1852, a Welsh geologist, John Davis, found gold near Krugersdorp. He presented his gold sample to the Z. A. R. government. Anxious about the potential impact of this discovery on the Boers’ rustic lifestyle and their precarious independence, the government purchased the gold from Davis, and then deported him. In 1853, Pieter Marais (who had gained prospecting experience in California and Australia) panned alluvial gold in the Jukskei River. He acted with the government’s consent, granted after he had sworn to keep his discoveries secret. In 1874, small-scale mining operations were begun in the Magaliesberg, where an Australian, Henry Lewis, had discovered gold deposits. In 1878, David Wardrop found gold in quartz veins at Zwartkop, north of Krugersdorp. In 1881, Stephanus Minnaar came across gold on the farm Kromdraai, near the Cradle of Humankind. The challenge, however, was to find the precious metal in sufficient quantities to render gold mining a commercially lucrative proposition. Prospectors explored streams in the northern Witwatersrand and west of Krugersdorp, but made no progress in locating the elusive El Dorado of southern Africa. Meanwhile, alluvial deposits had been found at Pilgrim’s Rest, leading to a fleeting gold rush to the eastern Transvaal.

The brothers Harry and Frederick Struben, as well as Jan Gerritze Bantjes (the son of the coloured man who had acted as the voortrekkers’ amanuensis and who had imparted basic literacy skills to a juvenile Paul Kruger), were among the most persistent early prospectors on the Rand. They discovered quartz gold in the so-called Confidence Reef on the farm Wilgespruit in 1884, but this reef was exhausted within a year.

In March 1886, an outcropping (soon to be called the Main Reef) was found, quite fortuitously, on Gerhardus Oosthuizen’s farm Langlaagte. Some say that the Lancastrian coal miner George Walker discovered this reef. Another itinerant English prospector, George Harrison (who had previously worked in Australian mines) obtained a prospecting licence in respect of Langlaagte in May 1886. However, he thought that this discovery was yet another false dawn. He decided to move on in a quest for greener pastures, and disposed of his Langlaagte claim for the princely sum of £10. Alas: beneath lay the richest goldfield ever found.

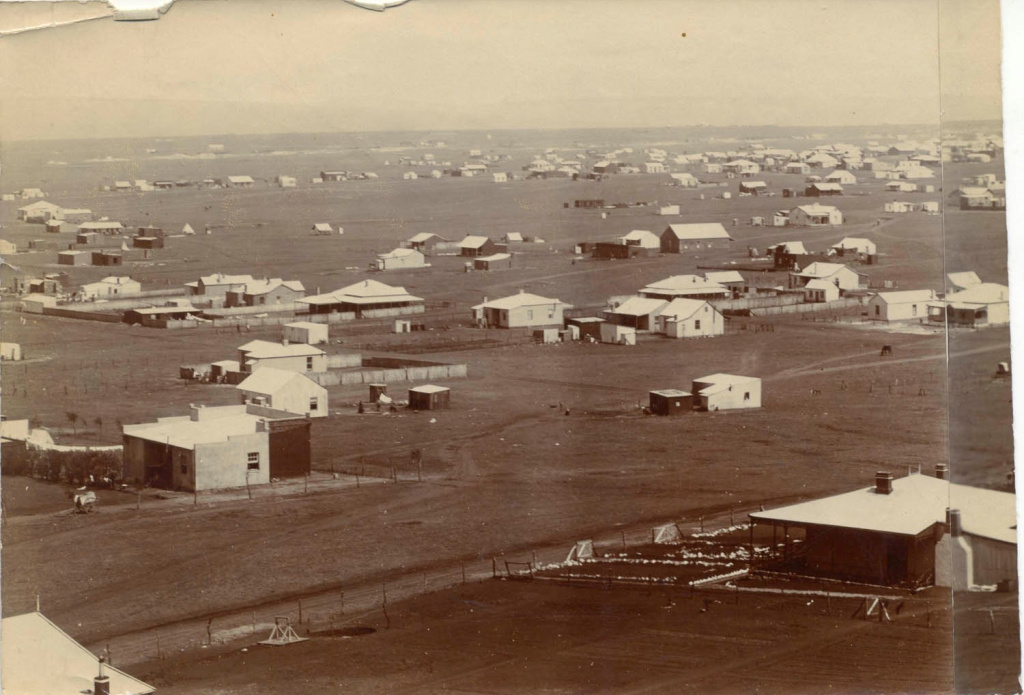

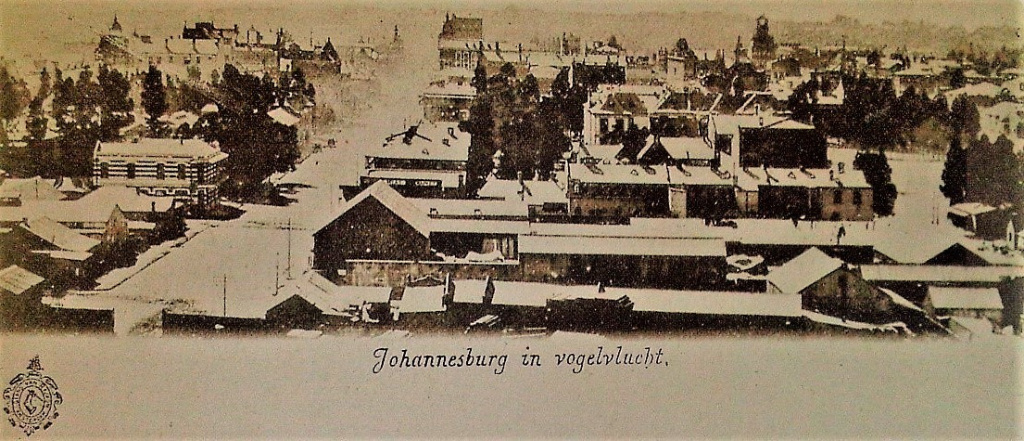

The discovery of this rich auriferous reef provoked a gold rush that signalled the end of bucolic tranquillity in the southern Transvaal. A mining camp mushroomed on the dusty veld as prospectors and diggers began to converge on the area. It would, within six years, become the largest town in southern Africa. Within a decade, it would make the Z. A. R. – until then an anarchical and bankrupt little state – the wealthiest country in Africa. By the turn of the century, the Z. A. R. was to surpass Russia, Australia and the United States of America to become the world’s leading gold producer, generating more than a quarter of the world’s gold.

The initial mining camp was located in the vicinity of the present-day Johannesburg magistrate’s court. It was known as Ferreira’s Camp, named after Colonel Ignatius Ferreira. He was a Boer adventurer upon whom the British authorities had bestowed the status of Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George (entitling him to the post-nominal letters C. M. G.) in gratitude for his role in the war that had deposed the Pedi king Sekhukhune in 1879. Ferreira had scurried to the Witwatersrand upon receiving news of the discovery of the Main Reef. Soon the camp was teeming with tents and wagons as newcomers arrived daily from far and wide. By September 1886, some 400 people lived in Ferreira’s Camp, which soon boasted prefabricated iron and timber buildings. Two other camps were established: Meyer’s Camp on the farm Doornfontein, and Paarl Camp. The latter was nicknamed Afrikander Camp; many people from the Cape Colony settled there. By October 1886, Paarl Camp possessed a general store, a blacksmith, a butchery and a bakery (and, perchance, even a candlestick manufacturer).

The Z. A. R. government soon recognised the need for residential arrangements of a more structured nature than these makeshift camps. An area known as Randjeslaagte (a triangular tract situated between the farms Braamfontein, Doornfontein and Turffontein) was deemed a suitable location for a village. On 5 October 1886, the Surveyor-General, Johann Rissik, sent a plan for the town to be laid out at Randjeslaagte to the surveyor, Josias Eduard de Villiers. Anecdotal accounts suggest that Rissik remarked casually that the town would be named Johannesburg (after himself and the local field-cornet, Johannes Meyer). This name gained currency by word of mouth, such that the State Secretary affirmed the name to the Mining Commissioner on 9 October 1886. Stands in the village were auctioned on 8 December 1886. While some stands were sold for £10, others were knocked down for as little as sixpence. A chemist supposedly secured a plot in exchange for a bottle of medicine. Two years later, these erven were to change hands for as much as £750 each.

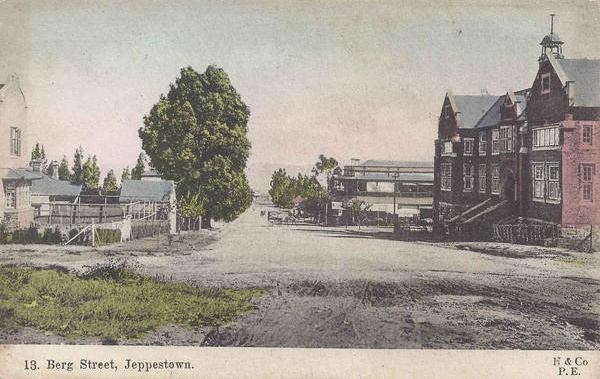

The tented camps dwindled as a dorp of corrugated iron buildings developed and expanded north of the mines located along the Main Reef Road. Areas such as Jeppe’s Town (where working-class immigrants erected their dwellings) and Doornfontein (where the affluent new ‘Randlords’ began to construct their opulent residences) were soon added to the ever-expanding map of the town.

The influx of uitlander (foreigner) immigrants that followed the discovery of the Main Reef gave the settlement a cosmopolitan character that it retains in its modern incarnation: the mêlée of those who arrived here included Cornish and Australian miners, Scottish and American engineers, Germans, Jews (many from Lithuania), Frenchmen and Indians. Before long, these fortune-seekers were followed by opportunists, speculators, capitalists, trade unionists, gamblers, gangsters, pimps, prostitutes and purveyors of alcoholic beverages (not necessarily in that sequence).

Soon Johannesburg had the insalubrious atmosphere of a rough-and-ready frontier town. In 1888, some 500 bars were trading in an area of about 1.5 square miles. Many who flocked hither were not people ‘who would demonstrate the higher side of European civilization to the Boers.’ Not a dozen men in Johannesburg, hyperbolised The Times correspondent Flora Shaw in 1892, could distinguish a violin from a vegetable. The town, she said, was ‘hideous and detestable, luxury without order, sensual enjoyment without art, riches without refinement, display without dignity.’ In 1898, Olive Schreiner termed Johannesburg a ‘fiendish, hell of a city which for glitter and gold, and wickedness, carriages and palaces and brothels and gambling halls, beat creation.’ She described Johannesburg as ‘a city given over to lust: lust of money in the first place, lust of pleasure, lust of excitement; and the tone of our sexual morality springs from this general attitude.’ By 1895, the town had 97 bordellos from which filles de joie of various nationalities plied their trade. Little wonder that the Cape politician John X. Merriman described Johannesburg as ‘Monte Carlo superimposed on Sodom and Gomorrah’.

That the Witwatersrand of the 1880s and 1890s was, from a moral and cultural perspective, a joyless landscape admits of no doubt. In his Historical Account of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, 1701-1900 (1901), Charles Frederick Pascoe wrote:

‘Generally speaking, while the goldfields added enormously to the responsibilities of the [Anglican] Church, they did not increase its pecuniary resources, the wealth being greatly in the hands of Jews, Wesleyans, Presbyterians, and worshippers of mammon. Hence, in 1897, the large European population along the mines were described by the Bishop [Bousfield, about whom we shall read more] as “godless to the last degree, but in great measure because when they come hither no man cares for their souls; a shifting population, here to-day, there to-morrow, and gone altogether ere long.”’

So much for the social and spiritual state of the ‘European’ inhabitants of the Rand. The same author provides an indication of the impact that developments here in the preceding decade had had on the African population, and of the extent to which the Church was ministering to their needs:

‘Mainly owing to lack of means and to the variety of tongues and tribes, little had been done up to 1899 for the native mining population at Johannesburg, at that time numbering 100,000, the native congregations there being drawn almost entirely from those living in the town and those engaged in domestic service. … From the white man the natives were learning to drink spirits of the vilest, to plunder on a large scale, to wear clothes; but of Christ and His Church and His robe of salvation nothing. The moral deterioration of the native miners attracted the notice of the Natal magistrates and of Archdeacon Johnson, of Zululand, who was enabled, in 1897, to make provision for the spiritual welfare of five hundred of his native Christians who had gone to work in the mines. The subject generally has also engaged the attention of the South African Bishops, and one of the most striking incidents of the Provincial Synod in 1898 was a speech by Mr Tracey, a Johannesburg layman, on the Rand as a field for Mission work and its crying need. The importance of such work is increased by the fact that the natives return to their own people carrying with them influences for good and evil. In 1898 schemes were submitted to the Society with a view to the establishment of a great Mission centre at Johannesburg for the natives employed in the mines, but action was necessarily deferred in consequence of the war of 1899-1900.’

But in mentioning ‘the war of 1899-1900’ we are getting ahead of ourselves chronologically.

The bulk of the white immigrants in the Z. A. R. came from the United Kingdom: 8,600 people relocated from the U. K. to southern Africa between 1885 and 1898. Most came to Johannesburg, with an incongruous result: while the majority of the British Cape Colony’s white citizens were Afrikanders, paradoxically most of the white people in the Boer republic were British immigrants. Johannesburg had the ambience of a British colonial city – more so than Cape Town, which still reflected its Dutch provenance. Apart from the street names, there were no signs of Johannesburg being situated in a Dutch-speaking country. Many years later, C. W. Kearns O. J. (one of the first boys enrolled at St John’s College in 1898) would recall: ‘A strange fact about Johannesburg was that, although it was in the [Boer Republic], nearly everyone spoke English and even the Government servants addressed one in English, unless they were first addressed in the Taal (or Low Dutch)’.

Political intrigue

All the while, trouble was brewing on the political front. Influential figures in Lord Salisbury’s British government were developing an interest in the Transvaal’s mineral wealth as a basis for maintaining imperial supremacy. Biweekly shipments of gold to London provided the assurance by which the City’s financial markets maintained the supremacy of sterling without having to accumulate large reserves of gold in the Bank of England’s vaults. However, international demand for gold was exceeding diminishing supplies. As such, Britain had an interest in ensuring optimal conditions for gold production on the Witwatersrand, and that the gold was exported to London rather than Berlin – an imperative rendered all the more clamant by the Z. A. R.’s increasing toenadering with Germany.

Mine owners were on a collision course with President Kruger, whose policy of monopolistic concessions (often granted to his cronies) prevented mining companies from procuring supplies of materials (especially dynamite) and labour on their own, cheaper terms. In this context, a body known as the Reform Committee was fomenting plans to advance the political aspirations of the aggrieved uitlanders. In 1890, the Volksraad had restricted the franchise to white men who had resided in the Z. A. R. for fourteen years or longer, thus disqualifying most of the immigrants (who happened to be the major contributors to the fiscus). However, agitation for the vote was a mere pretext for promoting a different agenda; most uitlanders regarded themselves as temporary visitors and had no intention of remaining in the Z. A. R. once they had made their intended fortunes. Conferral of voting rights would have had as its corollary the assumption of civic duties, including commando service – not a prospect that these sojourners relished. Kruger’s youthful Attorney-General, Jan Smuts, estimated that, if the franchise were to be offered to the uitlanders, not ten per cent of them would accept it. Their hardships were greatly exaggerated, and political capital made out of them. The uitlanders did have some legitimate grievances, though: the lack of running water and sanitation services made the Rand a decidedly unpleasant place, especially in summer.

Seeking to advance his economic interests in Consolidated Goldfields, Cecil John Rhodes (then Prime Minister of the Cape Colony) engaged in a conspiracy with the Reform Committee aimed at seizing control of the Z. A. R. – or, expressed in terminology of more recent vintage, bringing about ‘regime change’. At the end of 1895, Rhodes’ associate, Dr Leander Starr Jameson, led a cavalry invasion of the Transvaal. Jameson (who had previously been made an induna by Matabele chief Lobengula) boasted that, with 500 sjambok-wielding men under his command, he could drive the Boers out of the Transvaal, and that ‘anyone could take the Transvaal with half a dozen revolvers.’ Famous last words: the coup plot backfired when a planned simultaneous insurrection by the uitlanders did not materialise. The extent of uitlander opposition to Kruger had been over-estimated by Rhodes, Jameson and the other conspirators. Boer commandos captured Jameson’s men as they approached the Rand. The role of Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary in Lord Salisbury’s government, in the conspiracy – how much he had known beforehand, and whether he had sanctioned the raid with a nod and a wink – has provoked much controversy among historians ever since. The likelihood is that his hands were not squeaky-clean.

Chamberlain’s vision for southern Africa was one in which the Z. A. R. and the Orange Free State would enter into a federation with the Cape Colony and Natal as part of the British Empire. The British High Commissioner in southern Africa, Sir Alfred Milner, believed that such a result could only be accomplished by war. The pretext for war was provided by the continuing uitlander crisis. Towards the end of 1898 (shortly after St John’s College had come into existence), uitlander organisations, encouraged by elements within the British government, intensified their campaign for political rights in the Z. A. R. If allowed to vote, the uitlanders’ numerical superiority over the Boer burghers would allow them to seize control of the state via the ballot box. In turn, that would facilitate the implementation of reforms by the mining houses to reduce production costs (including the ‘ridiculously high’ wages of African labourers and the cost of dynamite, kept artificially high through a monopoly concession) and thus maximise profits for shareholders.

Shortly before Christmas 1898, a boilermaker from Lancashire, Thomas Edgar, became embroiled in a drunken brawl with an uitlander neighbour. While resisting arrest, Edgar was shot dead by a Z. A. R. policeman. The policeman was charged with murder but the prosecutor reduced the charge to homicide and released the accused on bail. This incident sparked protests by incensed uitlanders, who compiled a petition calling upon Her Britannic Majesty, Queen Victoria, to intervene to end the ‘intolerable state of affairs’ in the Z. A. R.

In an effort to defuse the situation, Smuts sought to strike a deal with the mining companies. The astute Cambridge-trained lawyer invited Percy FitzPatrick (who was to acquire fame as the author of Jock of the Bushveld, published in 1907) to act as the principal negotiator for the mining houses. He had been imprisoned on account of his complicity in the Jameson conspiracy, and had been released on parole on condition that he would abstain from all political activity for three years. Smuts now waived this condition to enable FitzPatrick to conduct the negotiations. But FitzPatrick leaked the confidential terms of the ‘great deal’ to The Star, thus causing the negotiations to collapse. FitzPatrick then travelled by rail to Cape Town, where, on 31 March 1899, he asked Milner to forward a petition, signed by 21,000 British subjects on the Rand and calling on the British government to intervene, to London. By mid-1899, the outbreak of war between Britain and the Z. A. R. was imminent.

Education in early Johannesburg

When Johannesburg was founded in 1886, public education in the Z. A. R. was regulated by the Education Law of 1882. The earlier Education Law of 1874 had provided that government schools in the Z. A. R. (only a handful of such schools was in existence) were to be non-denominational and that instruction was to be in Dutch or English, at the will of parents. By contrast, the Education Law of 1882 provided that a school would only receive a government subsidy if Dutch was its medium of instruction. However, this clause was not enforced rigidly and, until 1892, English-medium schools experienced little difficulty in obtaining subsidies.

Almost as soon as the Main Reef was discovered, elementary schools – many of them of dubious standard – began to operate in Johannesburg. A Mr Duff ran a school in Ferreira’s Camp, which had 21 pupils by the end of 1886. On 23 July 1887, the first government school in Johannesburg was established. The school, whose headmaster was the Revd Mr Piley (or Riley – the sources are inconsistent on this score), was accommodated in the local Dutch Reformed Church, and Dutch was the medium of instruction. The 1887 annual report of the Superintendent for Education recorded the existence of two other schools founded in 1887, both of which had been set up under the auspices of the Dutch Reformed Church and catered for the children of its congregation.

Catholic religious orders played an important role in launching educational institutions in Johannesburg. In 1886, Pope Leo XIII constituted the Transvaal an independent prefecture under the jurisdiction of the Rt Revd Odilon Monginoux of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who was the first Prefect Apostolic of the Transvaal. On 20 July 1886, Fr John de Lacy O. M. I. visited the Rand. He applied to the government for a piece of land large enough to accommodate a church, a school and houses for the teachers. On 18 July 1887, the State Secretary replied that a double stand, free of purchase price and transfer duties, would be granted to each church that applied for such a facility. Fr Monginoux then acquired the block of land now bounded by Fox, Main, Von Wielligh and Smal streets, where he built a diminutive chapel, a convent and a girls’ school. The Bishop of Natal, Monsignor Charles Jolivet O. M. I., transferred six French Holy Family sisters from Pietermaritzburg to take charge of this school, which opened on 1 October 1887. By the end of 1887, the convent had 75 pupils. The school moved to Doornfontein in 1895, and became known as the East End Convent. In 1905, the Holy Family sisters also founded Parktown Convent School (now Holy Family College).

On 2 November 1887, Miss Frances Buckland started teaching in a house on the corner of Jeppe and Rissik streets. Her school eventually developed into Cleveland High School and later became Johannesburg High School for Girls, situated in Barnato Park.

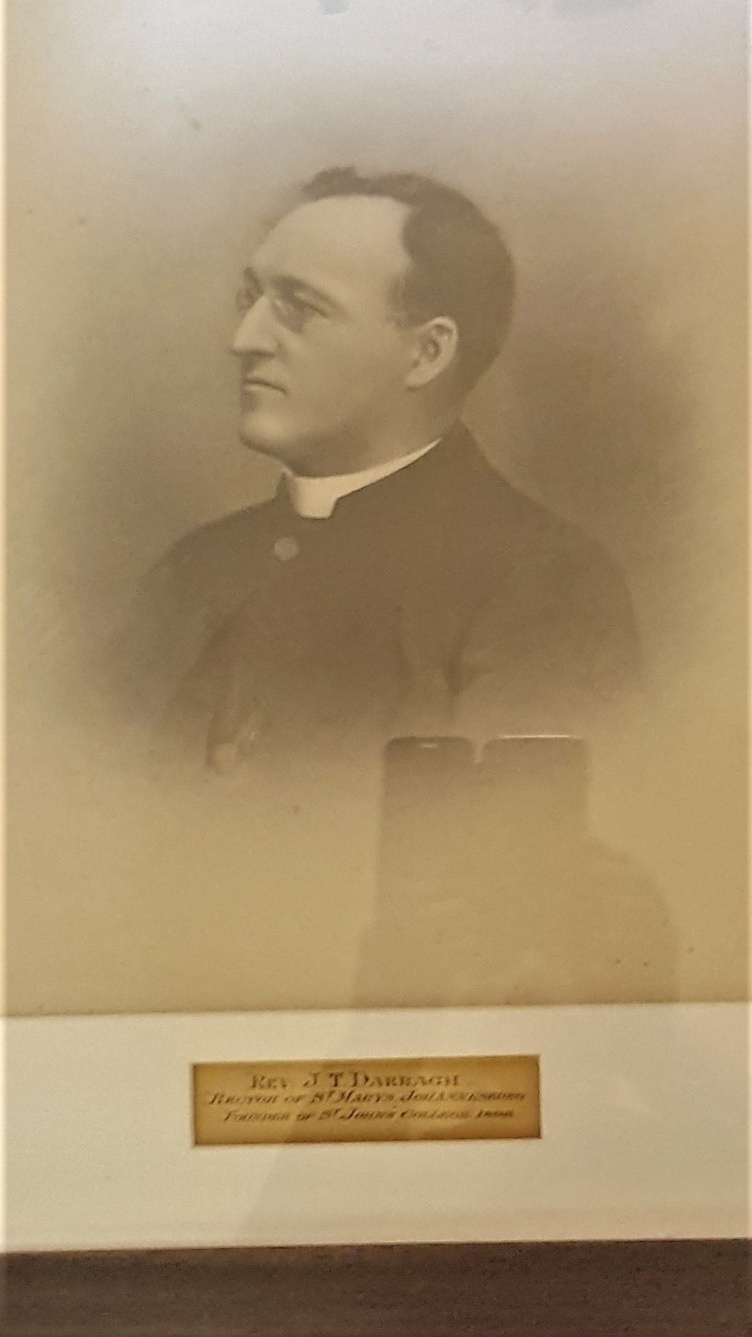

Meanwhile, on 11 June 1887, the Revd John Thomas Darragh, the first Anglican priest to be stationed on the Rand, had arrived from Kimberley. A mammoth tome on the history of Christianity in Africa observes concisely: ‘The Anglican community at Kimberley was fortunate to have as its leader J. T. Darragh, a temperamental Irish Anglo-Catholic, later posted to Johannesburg.’ He was ‘full of veneration for the medieval Church of Ireland with its colour and drama, [and] emphasized ritual in an unmistakable way.’ Born at Castle Finn, County Donegal, in the north of Ireland on 8 December 1853, Darragh had gone to The Royal School, Raphoe, founded by Royal Charter of King James I in 1608. He had won a scholarship to The Royal School, Armagh, whence he had gone up to Trinity College, Dublin, as a Foundation Scholar. Here he had distinguished himself, being Classical Hebrew and Divinity Prizeman, and had become a Fellow of Trinity College. He was ordained in 1880, and became curate of All Saints, Grangegorman, County Dublin.

He was still young – only 33 years old – when he arrived to take charge of the Anglican Church’s Witwatersrand Mission, but he had cut his parochial teeth in the rough and tumble world of the Kimberley diamond fields, where he had been the Anglican curate for six years. He was an energetic and enterprising man who immediately plunged himself heart and soul into the life of the burgeoning and bustling mining community. It was not only the Anglican parishioners who derived benefit, for Darragh worked unstintingly among all sectors of the village. For instance, the small community of Greek Orthodox settlers in Johannesburg had no archimandrite, and so approached Darragh to perform marital and baptismal rites. He sought and obtained permission from his own Bishop and from the Orthodox Patriarch – and then, having already learnt to speak Dutch, he proceeded to learn modern Greek (a task made somewhat easier by the fact that he had studied classical Greek at university), as well as the Orthodox liturgy and rituals.

Darragh was the driving force behind the creation of St Mary’s College for Girls, which commenced instruction in the hall of the red-bricked St Mary’s Church, at the south-west corner of Eloff and Kerk Streets, on 6 January 1888. The first teacher was Miss Lettie Impey. The school later moved to a new building at the corner of Berg and Marshall Streets in Belgravia, with Miss Kathleen Holmes-Orr as headmistress.

Around the same time, the Revd Mr Darragh brought into existence St Mary’s School for Boys, which was set up as a choir school for St Mary’s Church. The origins of St John’s College can be traced back to this school. The first headmaster of St Mary’s School for Boys was Mr F. Crane (presumably unrelated to his latter-day namesake, the radio psychiatrist of the 1990s television ‘sitcom’ Frasier). The school was based on the model of British grammar schools, and provided instruction in Dutch, French, Latin, Greek, history, geography, mathematics and, of course, singing. Initially, the school shared the church hall with the Girls’ College. School fees varied from 10s. to £1 per term, depending on the boy’s level of seniority.

In June 1888, Mr Herbert Goodwin took office as headmaster of St Mary’s School for Boys, which soon grew to the extent that it had to relocate to the hall of the Presbyterian Church. The school was inspected by the Z. A. R. education authorities at the end of 1888. The inspection was passed with flying colours, especially in respect of the criterion pertaining to the teaching of Dutch, as a result of which the school received a ‘very liberal grant’ from the state.

The Superintendent of Education inspected St Mary’s School for Boys again in February 1890. By that time, the principal was the Revd Henry Bindley Sidwell (later headmaster of Pretoria Diocesan School and subsequently Bishop of George). The school then had 160 pupils on its roll (although fifty of them were absent on the day of the Superintendent’s inspection, due to heavy rain). Subjects such as German, drawing, accountancy and music had been added to the curriculum. The next inspection, held on 24 February 1891, also produced a satisfactory report.

At the request of the Oblate Fathers, men from the Teaching Congregation of the Marist Brothers came from Cape Town to Johannesburg and, under the leadership of Brother Frederick, started Marist Brothers’ Sacred Heart College, at 30 Koch Street, with fourteen boys in October 1889. ‘Here there was not only good schooling, but cricket, football and other team games were encouraged. The moral standing was high.’ In 1895, the school’s cadet corps formed a guard of honour for President Kruger at the Agricultural Show; Oom Paul was greatly impressed by the boys’ smart and soldierly bearing.

Marist Brothers’ College acquired such a good reputation that some officials of the staunchly Protestant Z. A. R. government enrolled their sons as pupils at this Catholic school. In 1896, the school’s cricket club was affiliated to the Transvaal Cricket Union. By 1897, Marist Brothers’ had 500 pupils, and a neighbour lodged a complaint with the Superintendent of Education about ‘excessive’ playground noise during the lunch interval! During the Anglo-Boer South African War (1899-1902), the school’s enrolment dropped, but by 1905 numbers were back to 500 and the school was advertising the fact that it had ‘ample stabling for pupils’ horses’. Marist Brothers’ College remained Johannesburg’s premier boys’ school for some time.

On 11 April 1890, Chief Justice (later Sir John) Kotzé laid the foundation stone of St Michael’s College, an Anglican Church school in Commissioner Street. The driving force behind the creation of St Michael’s was the vicar of St Mary’s Church, the Revd John Darragh. A Jewish school was also opened in 1890. The Deutsche Schule in Edith Cavell Street was started in 1897.

In 1892, the Superintendent of Education, Dr N. Mansvelt, compiled a report in which he stated that some teachers in the Transvaal could not spell the words ‘Pretoria’ and ‘Potchefstroom’, and did not know the difference between a noun and an adjective. In the same year, the Education Law was amended to provide that all teachers in schools receiving government subsidies had to be members of a Protestant church; schools also could not receive subsidies in respect of Jewish and Catholic pupils. In addition, all textbooks had to be in Dutch, and no more than four hours per week could be devoted to instruction in other languages. These changes not only led to some schools losing their grants-in-aid; the number of children attending schools in the bigger towns (where there were concentrations of English-speaking, Catholic and Jewish people) dropped by some 40 per cent. These developments provoked agitation among those on the goldfields interested in education.

The government relented somewhat by purporting to introduce a subsidy payable to private schools in respect of English-speaking pupils who learnt Dutch. However, the subsidy was so hedged with conditions that it was well-nigh impossible for schools to earn it; at no point did more than 200 children qualify for this subsidy. On 7 March and 9 April 1892, the Revd Mr Darragh sent letters to the State Secretary, Dr W. J. Leyds, in which he stated that the previous Superintendent of Education, Ds S. J. du Toit, had undertaken in 1888 that English-medium schools such as St Mary’s and St Michael’s that also provided instruction in Dutch would qualify for state subsidies.

In response to the government’s obduracy in providing for the education of English-speaking children, a group of prominent uitlanders decided, in April 1895, to establish the Witwatersrand Council of Education. Members of the W. C. E.’s board included Sir Lionel Phillips and Sir Abe Bailey. The W. C. E.’s objects were to promote elementary education ‘suited to all nationalities and creeds’ and to counter the exclusive use of Dutch as medium of instruction in state-supported schools.

In October 1895, the W. C. E.’s director-general, John Robinson M. A. (Glasgow), a former principal of St Andrew’s School, Bloemfontein, compiled a report which recorded the parlous state of education in Johannesburg. According to this report, there were 55 schools for uitlander children in Johannesburg and environs; 31 of these operated in school and church buildings, the remainder being in private dwellings. Of the 187 teachers, only 46 held professional qualifications. Robinson estimated that 2,000 out of 6,500 white children of school-going age were not attending school. By 1897-’98, fewer than fifty white children in the entire Z. A. R. were in or above Standard VI.

By the end of 1896, the W. C. E. had acquired ownership of three schools, and had assumed control of and financial responsibility for three other schools. In 1897, the W. C. E. bought St Michael’s College and renamed it Jeppestown Grammar School – the progenitor of Jeppe High Schools for Boys and Girls. At the time, Jeppestown School, which was the Council’s flagship school, had 131 pupils.

The first schools for black children in Johannesburg were established by mission societies, notably Anglican, Wesleyan and Congregational societies. By 1896, there were seven mission schools for coloured and Indian children in Johannesburg, and four schools that accepted children of all races. The Revd John Darragh was involved in establishing two of the latter schools. The first was St Cyprian’s Mission School, founded early in 1890 in an area known as ‘Velskoendorp’, to the west of Brickfields and Burghersdorp (in the area of the present-day Newtown and Fordsburg). The area was inhabited by working-class people of all races and social backgrounds. The school was under the control of an Anglican priest, Fr Charles Barton Shaw. Miss Emma Shaw was the head teacher. She was assisted by a Miss Soamers. St Cyprian’s was initially granted a state subsidy, but this was cancelled when a government inspection revealed that the school had many coloured and ‘native’ boys among its pupils, sharing desks with white boys. Despite the withdrawal of the subsidy, the school managed to survive. It was closed temporarily during the Anglo-Boer South African War. After the War, it was reopened and run by Sisters of the Society of St Margaret (colloquially known as the East Grinstead Sisters, with reference to their convent in East Grinstead, Sussex).

Undaunted by the contretemps with the authorities about St Cyprian’s and its subsidy, Darragh started Perseverance School in November 1891. The school was intended to provide education to the children of poor English and Dutch-speaking parents. It was located in Ferreira’s Camp, and Miss E. Ham was the principal. The school was granted a government subsidy. However, as in the case of St Cyprian’s an inspection of the school conducted towards the end of February 1892 brought to light that coloured boys accounted for the vast majority of the school’s pupils. This subsidy, too, was then withdrawn on account of the illegal demographic composition of the pupil body.

So infuriated were the authorities when they discovered that Darragh’s two schools admitted children of all races, in circumstances where these schools had been granted subsidies on the explicit basis that only white children would be enrolled, that they reported Darragh to the Attorney-General for prosecution on account of his allegedly fraudulent conduct. No prosecution materialised. However, in retribution subsidies were withdrawn not only from Perseverance and St Cyprian’s schools, but also from St Mary’s School for Boys.

The 1896 census recorded that there were 16,038 children in Johannesburg. There were 62 schools, about 50 of which were for white children only. Only seven of these schools were state-aided. Some 7,000 white children could not read or write and were not being taught to do so. Only a minuscule proportion of black children enjoyed the privilege of formal education. - Dr Daniel Pretorius

Principal sources:

Agar-Hamilton Transvaal Jubilee: A History of the Church of the Province of South Africa in the Transvaal; Ash The If Man – Dr Leander Starr Jameson; Basson ‘Die Britse Invloed in die Transvaalse Onderwys, 1836-1907’; Behr ‘Three centuries of coloured education in the Cape and Transvaal’; Brodie The Joburg Book; Chilvers Out of the Crucible; Conan Doyle The Great Boer War; Council of Education, Witwatersrand History of Council; Cross ‘Foundations of a Segregated Schooling System on the Witwatersrand, 1900-1924’; Davenport South Africa: A Modern History; Fraser Johannesburg Pioneer Journals; Hamilton, Mbenga & Ross (eds) Cambridge History of South Africa vol 1; Horrell The Education of the Coloured Community; Horton The First Seventy Years; Le Roux ‘A Historical-Educational Appraisal of Parental Responsibilities and Rights in Formal Education in South Africa, 1652-1910’; König Seven Builders of Johannesburg; Kruger Goodbye Dolly Gray; Leonie ‘The Development of Bantu Education in South Africa: 1652-1954’; Leyds History of Johannesburg; Longford Jameson’s Raid; Lugtenburg Geskiedenis van die Onderwys in die S.-A.R.; Macmillan The Golden City; Mahuma ‘The Development of a Culture of Learning Among the Black People of South Africa, 1652-1998’; Malan et al Johannesburg: One Hundred Years; Malherbe Education in South Africa; Meredith Diamonds, Gold & War; Nasson The War for South Africa; Neame City Built on Gold; Pakenham The Boer War; Palestrant Johannesburg One Hundred; Ploeger ‘Onderwys en Onderwysbeleid in die Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek’; Rosenthal Gold! Gold! Gold!; Ross, Mager & Nasson (eds) Cambridge History of South Africa vol 2; Roux Time Longer Than Rope; Shorten Johannesburg Saga; Smith Pictorial History of Johannesburg; Smurthwaite ‘The private education of English-speaking whites in South Africa’; Stark Seventy Golden Years; Sundkler & Steed A History of the Church in Africa; Venter ‘Die groei van onderwysaangeleenthede in Johannesburg, 1886-1920’; Welsh History of South Africa; Wheatcroft The Randlords; Welham ‘John Thomas Darragh: Anglican Pioneer’